eBook - ePub

From Symptom to Synapse

A Neurocognitive Perspective on Clinical Psychology

- 382 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Symptom to Synapse

A Neurocognitive Perspective on Clinical Psychology

About this book

This edited volume bridges the gap between basic and applied science in understanding the nature and treatment of psychiatric disorders and mental health problems. Topics such as brain imaging, physiological indices of emotion, cognitive enhancement strategies, neuropsychological and cognitive training, and related techniques as tools for increasing our understanding of anxiety, depression, addictions, schizophrenia, ADHD, and other disorders are emphasized. Mental health professionals will learn how to integrate a neurocognitive perspective into their clinical research and practice of psychotherapy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Symptom to Synapse by Jan Mohlman, Thilo Deckersbach, Adam Weissman, Jan Mohlman,Thilo Deckersbach,Adam Weissman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Integrating Brain and Body Measures with the Study of Psychological Disorders

The scientifically informed practice of clinical psychology has taken an innovative new direction and is gaining momentum. This progress is largely attributable to the integration of research in affective, cognitive, and behavioral neuroscience with traditional clinical psychology. The decade from 1990 until 2000, known as “the Decade of the Brain” (Library of Congress; www.loc.gov/loc/brain/), produced the first wave of empirical studies on the neural bases of psychopathology. This research was made possible by technical advances in methodology and tools such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neural tract tracing methods, and behavioral paradigms that correct cognitive deficits or protect against further decline. The knowledge gained during and subsequent to this period is now being applied for the first time to enhance the recognition and treatment of emotional disorders. As a result, the focus on integrating biological and psychological perspectives has never been stronger. This new approach has been termed the neurocognitive perspective.

The neurocognitive approach has opened fresh avenues for research and innovation in clinical practice. In the past, the typical clinical trial utilized self-report and clinician-rated measures of symptom severity as primary indices of outcome. However, more recently, strategies for assessing and treating disorders have been expanded to include cognitive and biological variables (e.g., executive functions, indices of neurobiology, aspects of brain function). For example, scholars have begun to examine symptom- and diagnosis-specific brain-behavior relations, linking distinct neurocognitive profiles to cognitive (e.g., worry, cognitive distortions), emotional (e.g., fear, rumination, depressed mood), and behavioral dysfunction (e.g., inattention, impulsivity, compulsive behaviors), as well as symptom severity, comorbidity, and treatment response. These connections have been found across a number of common clinical populations including anxiety disorders (e.g., Legerstee, Tulen, Dierckx, Treffers, Verhulst, & Utens, 2010; Matthews, Mogg, Kentish, & Eysenck, 1995; McClure et al., 2007; Mohlman & Gorman, 2005; Roy et al., 2008, Weissman, Chu, Reddy, & Mohlman, 2012); mood disorders (e.g., Deckersbach et al., 2010; Siegle, Carter, & Thase, 2006; Weissman & Bates, 2010); attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; e.g., Barkley, 1997; Hale et al., 2009; Reddy & Hale, 2007); and disruptive behavior disorders (e.g., Clark, Prior, & Kinsella; 2002; Turgay, 2005). Recent studies have extended these findings, demonstrating the clinical utility of neurocognitive assessment in differential diagnosis and case formulation (Hale et al., 2011; Weissman et al., 2012) as well as the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral (e.g., Kuelz et al., 2006; Legerstee et al., 2010; Matthews et al., 1995; Mohlman & Gorman, 2005; Siegle et al., 2006); pharmacological (Hale, Fiorello, & Brown, 2005; Hale et al., 2011); and neurocognitive therapies (e.g., Kerns, Eso, & Thomson, 1999; Koster, Fox, & MacLeod, 2009; Vassilopoulos, Banerjee, & Prantzalou, 2009) in treating both affective and cognitive impairments in individuals with comorbid neuropsychological, emotional, and behavioral difficulties.

History, Evolution, and Professional Impact of the Neurocognitive Perspective

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how and when the neurocognitive perspective on clinical psychology first emerged; however, there were harbingers of this trend in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These ideas emerged as occasional speculation by researchers working in cognitive and affective neuroscience and just beginning to consider the bridge to practice.

One early example of the neurocognitive perspective was the proposition that executive functions (skills governed by the frontal lobes of the brain) facilitate the successful use of cognitive behavioral techniques (e.g., Hariri, Bookheimer, & Mazziotta, 2000; Martin, Oren, & Boone, 1991; Posner & Rothbart, 1998). Executive skills and the prefrontal cortex are known to contribute to the regulation and management of emotion (Posner & Rothbart, 1998) through processes such as reappraisal and verbal rehearsal (Koenigsberg et al., 2009: Ochsner et al., 2002; Ochsner & Gross, 2008). Recent fMRI data and other methods of neuroimaging have indeed implicated these neural areas in the effortful regulation of emotion (Beauregard, Levesque, & Bourgouin, 2000; Hariri, Bookheimer, & Mazziotta, 2000).

Other signs of the emergence of the neurocognitive perspective can be found in the domains of scholarly publication, the research priorities of funding agencies, the focus of professional groups, and as a presence in graduate training curricula. For instance, a 2009 Journal of Abnormal Psychology special issue on cognitive bias modification provided initial evidence that cognitive training techniques such as attentional bias modification may be effective in (1) reducing selective attentional processing of threat and (2) mitigating associated real-world anxiety vulnerability and state, trait, and clinical anxiety symptom severity. Results reported in this special issue further suggested that attentional selectivity may not only play a causal role in the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders but may serve as an important mechanism of therapeutic change. Another example is the 2011 issue of Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, which features a trio of articles discussing the process-based approach to research, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Each article highlights the use of brain and body measures as new tools for facilitating mental health through the investigation of learned helplessness, which is mechanistically related to mood disorders.

The growing interest in clinical applications of neurocognitive measures has also permeated the clinical, education, and public health sectors (Reddy, Weissman, & Hale, 2013). Increased demands from third-party payers for efficient, cost-effective, and evidence-based assessments and interventions, along with heightened public awareness of the value of neuropsychological assessment for diagnosis and treatment planning, have increased the implementation and promotion of these techniques among mental health service providers and policy makers. Additionally, the proliferation of books on the use of neuropsychological assessment in clinical practice (e.g., Hale & Fiorello, 2004; Reddy et al., 2013) has contributed in part to changes in doctoral and postdoctoral education across the nation. Neuropsychology postdoctoral fellowships and institutes (e.g., Fielding Institute) have shown significant growth and are in high demand for advanced professional training. For example, a number of clinical, counseling, and school psychology doctoral and pre-doctoral internship programs are placing greater emphasis on didactic curricula and clinical training in neuropsychological assessment and neuroscience.

The research agenda promoted by the U.S. government has also shifted to emphasize clinical application and an interdisciplinary approach. For example, the Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC), launched by the National Institute of Mental Health, is an ambitious call for researchers to develop, in essence, a transdiagnostic and neurocognitive system for classifying psychopathology. This new system would hinge upon basic mechanisms and dimensions of functioning that can be studied at different levels of analysis (e.g., neural, behavioral). Thus, rather than developing interventions that are disorder specific, the RDoC targets processes such as fear circuitry and attentional bias, which cut across disorders. On a global scale, the federal government (e.g., National Institutes of Mental Health, U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences) has begun to regard clinical-translation research as a priority area for empirical investigation and grant funding.

Recently, the first graduate training programs offering formal training in neurocognitive approaches have emerged. Teachers College Graduate Program in Neuroscience and Education focuses on the educational and clinical implications of recent advances in understanding brain-behavior relationships. One objective of the multidisciplinary program is to prepare a new kind of specialist: a professional with dual preparation able to bridge the gap between research on underlying brain, cognition and behavior, and the problems encountered in clinical settings. A second objective is to provide rigorous training and relevant experiences that would allow students to further their knowledge and make links between neuroscience, cognition, and clinical practice.

Additionally, there are a number of professional meetings that focus on various topics of particular interest to those working from the neurocognitive framework, including the annual Wisconsin Symposium on Emotion and the Cognitive Remediation in Psychiatry conference held in New York. Efforts to formalize and advance the neurocognitive approach can also be seen in various professional groups. One of the first organized groups of clinical psychologists in the United States was likely to have been the Neurocognitive Therapies/Translational Research Special Interest Group (Mohlman & Deckersbach, 2009) of the Association for the Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. This cadre of approximately sixty-five researchers and clinicians has attempted to formalize the neurocognitive perspective and promote the use of brain and body measures through research symposia, clinical training workshops, published articles, and other means. Many of these individuals have authored chapters in this volume. Likewise, national organizations such as the American Psychological Association, National Academy of Neuropsychology, and Society for Neuroscience are recognizing the important influence of neuroscience and neuropsychological assessment in modifying interventions and developing innovative treatments.

Over the past few years, a number of books have been published that showcase the clinical use of neuropsychological assessment, neuroscience, and intervention (e.g., Borod, 2000; Castillo, 2008; Gross, 2007; Hunter & Donders, 2007; Riccio, Sullivan, & Cohen, 2010). These noteworthy texts have focused primarily on neuropsychological interventions with individuals with complex medical conditions (Castillo, 2008) and/or developmental and neurological disorders (Hunter & Donders, 2007; Noggle, Davis, & Barisa, 2008; Riccio et al., 2010). What is missing, however, is a comprehensive text that presents models integrating neuropsychological assessment, brain and body measures, and intervention for individuals with common emotional and behavioral disorders and related conditions across the life span. This volume serves to fill this critical void in the literature.

Benefits of the Neurocognitive Perspective: Conceptualizing and Assessing Emotional Disorders

There are many compelling reasons for developing a neurocognitive perspective of emotions and disorders. As noted by Rottenberg and Johnson (2007), emotion is a multidimensional construct, often conceptualized as a constellation of interacting behaviors, thoughts, and patterns of neural and physiological arousal. This structure begs for collaboration across psychological disciplines. With collaboration, researchers are exposed to new tools and the new ways of thinking to accompany those tools, and the opportunity to merge innovative ideas. A neurocognitive approach could aid in more refined definitions and characterizations of disparate and associated emotion states. Thus, bridging interdisciplinary gaps enhances knowledge of basic mechanisms of emotion and mood states. Such mechanisms might be prone to manipulation, which could benefit patients efficiently and effectively.

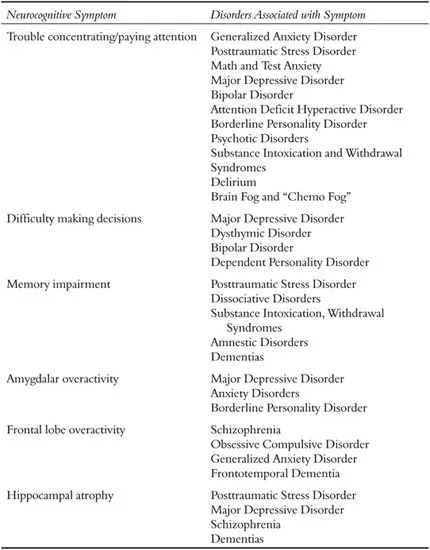

Another compelling reason for adopting a neurocognitive perspective is to better recognize and measure severity of symptoms, syndromes, and disorders. Many disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) are characterized by deficits in cognitive abilities and aberrant patterns of neural activation (Table 1.1); however, such variables have taken a distant backseat to mood symptoms in the diagnosis and measurement of clinical outcome.

One relevant example of how the neurocognitive perspective has contributed to our understanding of specific disorders can be found throughout the literature on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). In recent functional neuroimaging studies, distinct patterns of brain activation show an association with disparate OCD symptom dimensions (e.g., checking versus contamination; Deckersbach, Savage, & Rauch, 2009). In addition, in the child literature, research suggests that the use of neurocognitive methods may be appropriate to assess more general ADHD-related attention deficits versus more emotion-based, threat-related automatic biases in attention found in children with anxiety disorders (e.g., Puliafico & Kendall, 2006; Weissman et al., 2012). Consistent with this position, Weissman et al. (2012) found that ADHD youth demonstrated poorer performance on selective, sustained, and shifting attention relative to anxious youth, who exhibited greater attentional biases toward threatening facial cues, which could have implications for effective treatment, treatment matching, and the use of adjunctive neurocognitive techniques. For instance, executive attention training may be preferred for children with ADHD (Kerns et al., 1999), while attentional bias modification may be effective for children with anxiety disorders (Riemann, Amir, & Lake, 2010). In addition, pharmacological treatments may vary for these children based on whether the anxiety or ADHD symptoms predominate (e.g., Hale et al., 2005).

Table 1.1 Cognitive and neurobiological symptoms and associated DSM-IV disorders

Benefits of the Neurocognitive Perspective: Optimizing Treatment

The neurocognitive perspective also affords benefits for treatment. Current interventions, while more effective than ever, still fall short of optimal effectiveness (Lazar, 2010). Given that pharmacotherapy and psychological interventions appear to act on different brain circuits (Goldapple et al., 2004), it was originally hoped that the combination of psychosocial and pharmacological strategies would lead to enhanced therapies for frequently occurring disorders such as anxiety and depression. However, especially for anxiety disorders, the majority of studies indicate minimal benefits of combining medication and therapy over the use of one strategy on its own (Simpson & Liebowitz, 2005).

Similarly, for bipolar disorder, antidepressant medication does not appear to offer any benefits for treating a depressive episode, whereas intensive psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy, family-focused therapy, or interpersonal and social rhythm therapy) has been shown to shorten the length of depressive episodes (Miklowitz et al., 2007). Overall, it has been recognized that for many diagnostic groups, neurocognitive impairments contribute substantially to patients’ inability to function in daily life. For example, difficulties in declarative memory (the ability to learn and remember new information), attention, and executive functioning in schizophrenia have been linked with patients’ difficulties to work or function in general (McGurk & Mueser, 2004).

Consequently, cognitive impairments h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: Integrating Brain and Body Measures with the Study of Psychological Disorders

- 2 Tools of the Neurocognitive Psychologist

- 3 Pediatric Anxiety: A Neurocognitive Review

- 4 Neurocognitive Perspectives on Anxiety and Related Disorders

- 5 Neurocognitive Aspects of Anxiety in Cognitively Intact Older Adults

- 6 Neurocognitive Approaches in the Treatment of ADHD

- 7 Neurocognition in Schizophrenia: A Core Illness Feature and Novel Treatment Target

- 8 Pediatric Depression: Neurocognitive Function and Treatment Implications

- 9 A Neurocognitive Approach to Major Depressive Disorder: Combining Biological and Cognitive Interventions

- 10 Bipolar Disorder: A Neurocognitive Perspective

- 11 Treatment of Phantom Limb Pain: Application of Neuroscience to a Disorder of Neuroplasticity

- 12 The Neurocognitive View of Substance Use Disorders

- 13 Paving the Road to the Neurocognitive Clinic of Tomorrow: Appealing to Standards

- Index