Part 1: Staking claim, shaping space

The first European settlers in what is now the US saw the American landscape as virgin territory, raw and undeveloped. They brought with them tools and memories, patterns and conventions, which they used to shape their new homes. The tools and memories they retained for some time; the patterns and conventions, however, needed to be adapted to the new environments—quite different from those left behind in Europe—if people were to survive and prosper. The land shaped the people as they shaped it.

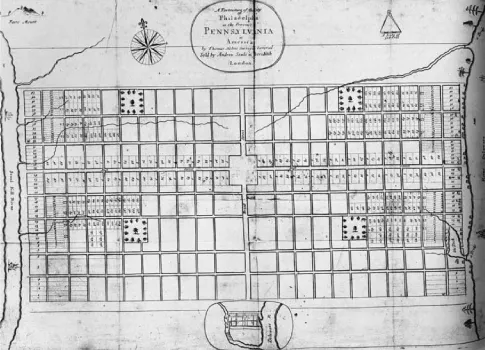

Never again would the American continent seem so utterly and frighteningly void of design as it did to these first settlers, so in need of ordering systems for its habitation and successful exploitation. As environmental historian John R. Stilgoe demonstrates, the grid provided Europeans with one of their first and most successful tools for ordering this space. Focusing in this excerpt on the grid’s practical and economic advantages, Stilgoe shows how the design of a mercantile city like Philadelphia became a template for shaping other towns and territories across the American continent.

While European settlers did not always recognize or appreciate their efforts, Native American groups had long preceded them in shaping the land for human habitation. Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton provide a broad introduction to Native-American architecture, one that extends across time, region, and culture. They consider technology, climate, economics, social organization, religion, and history as the major “modifying factors” in traditional Native-American building; meanwhile, they see buildings themselves as indicative of the elements dominating the lives of particular groups. A brief discussion of the architectural and cultural effects of contact with Europeans concludes their essay and points to two important, related themes: cultural borrowing, hybridity, and translation in architecture, and architecture’s role in the expression of cultural continuity and identity.

Seeking a foothold in the harsh, remote northern limits of New Spain, while dependent on Indian labor and restricted to the same limited range of materials available to local native groups, European settlers in what is, today, New Mexico, were likewise confronted by these issues. In establishing missions and “rationalizing” existing Indian construction techniques as they did, the Spanish aimed to assert a European presence in the “wilderness.” Marc Treib, an architect by training, offers here a detailed examination of the design, construction, and form of Spanish-colonial-era sacred spaces in New Mexico. Following this, Dell Upton, a former student of historical archaeologist James Deetz and folklorist Henry Glassie, looks at other spaces, both sacred and secular, through a different lens: as the material signs of culture. Upton considers the hierarchical ordering of spaces and the patterns of use and ritual found in certain English-colonial Virginia churches, courthouses, and dwellings. In these he finds evidence of deep social structures and of shifting conceptions of time, memory, and nature.

Further reading

Carson, C., R. Hoffman, and P. J. Albert (eds), Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1994.

Cooke, J. E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies, 3 vols, New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1993.

Cronan, W., Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, New York: Hill and Wang, 1983.

Cummings, A. L., The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625–1725, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1979.

De Cunzo, L. A. and B. L. Herman (eds), Historical Archaeology and the Study of American Culture, Winterthur, DE: Henry Francis Dupont Winterthur Museum, 1996.

Deetz, J., In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life, New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1996 expanded and revised edn.

Edgerton, S. Y., Theaters of Conversion: Religious Architecture and Indian Artisans in Colonial Mexico, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2001.

Garrett, W., American Colonial: Puritan Simplicity to Georgian Grace, New York: The Monacelli Press, 1995.

Pierson, W. H. Jr, American Buildings and Their Architects, Vol. 1: The Colonial and Neoclassical Styles, New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Reps, J. W., The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965.

Scully, V., Pueblo: Mountain, Village, Dance, New York: Viking Press, 1975.

St George, R. B. (ed.), Material Life in America, 1600–1860, Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 1988.

Sweeney, K. M., “Meeting Houses, Town Houses, and Churches: Changing Perceptions of Sacred and Secular Space in Southern New England, 1720–1850,” Winterthur Portfolio 28: 1 (1993): 59–93.

Upton, D. (ed.), America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups That Built America, New York: Preservation Press and John Wiley and Sons, 1986.

Upton, D. and J. M. Vlach (eds), Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture, Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

Wenger, M. R., “The Central Passage in Virginia: Evolution of an Eighteenth-Century Living Space,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 2 (1986): 137–149.

Chapter 1: National design: Mercantile cities and the grid

John R. Stilgoe

Everyone recognizes checkerboard America. Like a great geometrical carpet, like a Mondrian painting, the United States west of the Appalachians is ordered in a vast grid. Nothing strikes an airborne European as more typically American than the great squares of farms reaching from horizon to horizon.

Only the fields are noticeable from 20,000 feet. At lower altitudes flyers discern among them the scattered farmsteads connected by ruler-straight gravel and blacktop roads. They marvel at the pattern and scrutinize the fields and farmsteads, wondering what crops show up so yellow at midsummer and worrying that the farmers might be lonely. Few look closely at the lines that hatch the countryside below; the lines seem accidental, the result of pastures abutting wheat fields and the building of roads. Almost no one perceives the regular spacing of the lines or guesses that the lines predate the fields and structures.

Section lines, like lines on graph paper, made the grid and make it still. They objectify the Enlightenment in America. Late in the eighteenth century they existed only in surveyors’ notebooks and on the rough maps carefully stored in federal land office drawers. Here and there a blazed tree or pile of stones marked an intersection, but otherwise the lines existed only as invisible guides. Not until farmers settled the great rectangles platted by the surveyors and began shaping the land did the lines become more than legal abstractions of boundaries. Along them farmers built fences to mark their property limits and to divide livestock from corn, and along many they built roads too. Now and then a historically minded flyer, often a foreigner intrigued by the geometric regularity of the countryside below, swoops down and hedgehops above a section line, following it as Wolfgang Langewiesche did in 1939. “First it was a dirt road, narrow between two hedges, with a car crawling along it dragging a tail of dust. Then the road turned off, but the line went straight ahead, now as a barbed wire fence through a large pasture, with a thin footpath trod out on each side by each neighbor as he went, week after week, year after year, to inspect his fence. Then the fence stopped, but now there was corn on one side of the line and something green on the other.”1 On and on Langewiesche flew, following the half-abstract, half-physical line across pasture land and arable, through a small town, and on into farms again. “When I climbed away and resumed my course,” he remarked half-wonderingly, “I left it as a fence which has cows on one side and no cows on the other. That’s a section line.”2 Like many amateur pilots, Langewiesche appreciated section lines because they run rigidly north-south, east-west; despite being an eighteenth-century creation, they are a superb navigational aid. Nothing man has built into the American wilderness is more orderly.

On the ground, only the most perceptive travelers consciously recognize section lines. Here and there a hilltop offers a view of lines and right-angle intersections, but elsewhere the grid is masked by the slightly rolling topography that characterizes most of the Middle West. Farmers and other inhabitants of the grid country think nothing of the straight roads and property lines they have inherited from their forebears. Not until they drive east, into the coastal states and Kentucky, Vermont, and Tennessee, are they suddenly aware that behind them lies a landscape of more obvious order. All at once they recognize the absence of the geometrical structure that shapes their space, colors their speech, and subtly influences their lives, and they perceive the dominance of older, distinctly regional landscape skeletons.

MERCANTILE CITIES

William Penn introduced the grid to the English colonies in 1681, when he directed his agents and surveyors to lay out a city in Pennsylvania (Figure 1.1). Philadelphia was a city by intention, not accident, and it was markedly different from the few other large towns along the coast. Penn did not invent the urban grid—the towns of northern New Spain were ordered about a plaza and streets intersecting at right angles, and nine years before Philadelphia, Charleston in South Carolina was laid out “into regular streets”—but he emphasized the grid above walls, meetinghouses, and public squares. From the beginning, its streets defined and distinguished Philadelphia.

1.1 William Penn’s Plan for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1682 (from John C. Lowber, Ordinances of the Corporation of the City of Philadelphia, Philadelphia: Moses Thomas, 1812)

1.2 The City of Boston, Parsons and Atwater delineators, published by Currier and Ives, New York, 1873

Until the 1740s colonial space struck visitors as simply rural. Only Boston (Figure 1.2), Newport, New York, Charleston, and above all Philadelphia broke the uniformity of farming settlements. As late as the 1690s, even Boston scarcely impressed visiting Europeans, although it was the center of most New England shipping, the seat of the Bay Colony government, and frequently compared by its inhabitants to the “city of London.”3 But at the close of the seventeenth century, Philadelphia promised only an imminent urbanity; Boston seemed certain to retain its place as the foremost English “merchandise” town.

The city upon a hill envisioned by John Winthrop began as an agricultural settlement on a peninsula. Like all other New Englanders, its inhabitants occupied themselves with allocating house lots and planting land, and with regulating the use of common pasture, meadow, and woods. Two years after its founding, approximately forty houses, each surrounded by a vegetable garden and some already dignified by sapling fruit trees, clustered haphazardly about a meetinghouse. Bostonians worried about growing enough food for themselves and focused their attention on the poor soil and the daily adventure of agriculture in a new place and a new climate.4 Even as more and more immigrants landed at Town Cove and sought food, shelter, and seed, Bostonians behaved as did most other New Englanders, shaping the land and ordering society.

Seventeen years later 315 houses and 45 additional buildings bespoke Boston’s new role. England’s Civil War reduced immigration to a trickle after 1642 and deprived Bostonians of their entrepôt livings. All at once citizens discovered the necessity of locating new markets, and they directed their attention to the West Indies and Europe. At first Bostonians captured only the coasting trade, bringing lumber and cattle and cod from New Hampshire and the Grand Banks to the hungry plantations of the southern colonies and the West Indies, and carrying home molasses.5 The trade prospered as New England’s agricultural settlements produced larger and larger surpluses, and the Bostonians built larger ships and sailed for the Portuguese Islands, England, and the European continent in what became known as the triangular trade. Within two decades of the closing of immigration, Boston was something that other New England settlements except Newport were not, although exactly what puzzled visitors and natives alike. It was easy enough to see the physical differences, however, and traveler after traveler remarked on them.

Commerce weaned Bostonians from agriculture, and soon they jammed houses and other structures so closely together that houselot gardening almost vanished, at least near the waterfront. Craftsmen worked frantically erecting houses for newcomers like William Rix, who commissioned a one-room house, sixteen feet long and fourteen wide, with a cellar and loft, clapboarded walls and roof, and a timber chimney. It was an impossibly small house for a family man who made his living by weaving, and Rix requested a second structure to house his loom and other tools. Compared with Governor Winthrop’s “mansion,” Rix’s house was simple indeed, a clear objectification of Puritan hierarchical society. But the loom-shed acquired a special significance because it revealed that Rix did not farm full time and that his specialized occupation kept him busy enough to require and support a specialized structure.6 Craftsmen like Rix understood the necessity for specialized workspace, and Boston’s carpenters, brickmakers, limeworkers, masons, sawyers, brewers, bakers, coopers, tanners, butchers, smiths, shipwrights, sailmakers, ropemakers, joiners soon produced structures of every sort, each type adapted to a particular calling.

Weavers and other craftsmen bought most of their food and raw materials from husbandmen who lived in outlying agricultural settlements and who walked to Boston filled with anticipation not only of profits but of excitement. In Boston they exchanged their produce for cash or services or else bartered it for imported or manufactured items impossible to obtain in their home settlements. Retail shops blossomed along the narrow, twisting streets, catering mostly to Bostonians but also to countrymen. “The town is full of good shops well furnished with all kinds of merchandise,” remarked one inhabitant, and it was filled with shoppers too. By 1680 Boston supported twenty-four silversmiths, a sure sign of growing prosperity.

Six years after the founding of Boston the selectmen ordered that two “street ways” be laid out to accommodate the townspeople. Never again, however, did the town pay much attention to its growing traffic problem. More and more frequently it temporarily solved access problems by empowering individuals to open streets at their own cost; at the time the policy seemed sound. Boston received a new street or two, and the undertakers realized a profit by selling the abutting lots. Not surprisingly, such streets were narrow and crooked, but their very irregularity produced a wealth of changing views and surprises.7 That Bostonians thought in terms of streets rather than roads or ways is significant because in the late sixteenth century street had already acquired richly evocative connotations. The word no longer meant merely a road or cartway but a passage in a city or town, a pathway through the verticality made by houses and other structures, and often bordered with pedestrian sidewalks. Even more than the king’s highway, a street promised excitement and activity, and particularly the likelihood of meeting strangers, because street connoted above all else half-controlled urban chaos. Seventeenth-century Bostonians understood the connotation very well indeed, for as early as the 1650s their streets, in the words of one observer, were “full of girls and boys sporting up and down, with a continued concourse of people.” Strangers of every sort thronged the streets: newly arrived immigrants waiting while thei...