Introduction

All societies have to face the problem no one can financially support her- or himself during all periods of life. Low earnings capacity may be caused by, for example, sickness, disability, unemployment, child rearing, widowhood and old age. Thus, all societies have to organize support for those without earnings capacity. Three broad ways can be distinguished: the family, the market and the state. In most societies, all three ways co-exist with one of them being dominant. The family model is dominant in developing countries while in industrialized countries a state model, in the form of a pay-as-you-go public pension, is most common.

In this chapter we focus on loss of working capacity due to old age with a special focus on gender. The main objective is to relieve poverty in old age but also to offer an insurance when life expectancy exceeds the norm.

Differences in traditions and cultures significantly affect women’s level of activity in the labor market, but so, too, do economic conditions. Social and fiscal policy can be designed to economically reward and encourage women to remain in the home and “penalize” paid work by women (the breadwinner or single-earner model). Alternatively, they can be designed to encourage paid work and penalize women who remain at home (the individual or dual-earner model).

In the breadwinner or single-earner model, marriage enjoys a premium and a division of labor between husband and wife is encouraged. Economic policy supports reproductive work in the home through various measures such as: supplementary allowances for spouses and children in the social insurance system, and tax relief for men with wives at home and/or children. If widowed, a woman receives a widow’s pension since her pursuit of wifely duties in the home is assumed to have made it more difficult for her to re-enter the labor market. Such rules provide little incentive for women to engage in paid work thus making themelves economically independent of their husbands (Sainsbury 1996, Ståhlberg 2002a, 2002b).

In the individual or dual-earner model, the aim is to shape economic policy so that it encourages continuous participation by women in the labor market, making it possible for both men and women to reconcile parenthood with professional life. Here, both the social insurance and the tax systems are based on the individual and offer neither tax relief nor special allowances for a spouse working in the home. Earnings-related benefits in the social insurance system make paid work an attractive option. In the individual model, which promotes the goal of economic independence for all adults, the social insurance system contains no widows’ or widowers’ pensions.

It is rare for a country to adopt either the breadwinner model or the individual model in their pure forms. The normal case is that one of the models dominates and that legislation, taxes and transfers are designed accordingly.

In a system that is neutral to the chosen family pattern, social and fiscal policy neither favor nor disfavor market work vs. home work. Each adult gets a pension benefit in accordance with contributions. A widow’s/widower’s pension has to be paid for by the spouse. To safe-guard the system against the problem women may end up in poverty in old age because their spouses do not choose a survivor’s benefit (free-riding), mandatory joint-survivor annuities could be a solution.

Public pension systems, be they single- or dual-earner based, are mostly pay-as-you-go systems. In the industrialized world, aging, because of decreases in fertility and increases in life expectancy, puts a fiscal strain on public pension systems organized on a pay-as-you-go basis. Both cause increases in dependency ratios. Also, decreased fertility means a declining rate of return in such a system (making alternatives more attractive). In order for these systems to be sustainable, increased longevity can be handled by:

As for deferred retirement, the trend is, as is well known, actually the opposite, causing further pressure. Increased labor force participation and hours of work would lead to a lesser burden for those of active age. Measures for increasing female labor force participation and working hours might be an option.

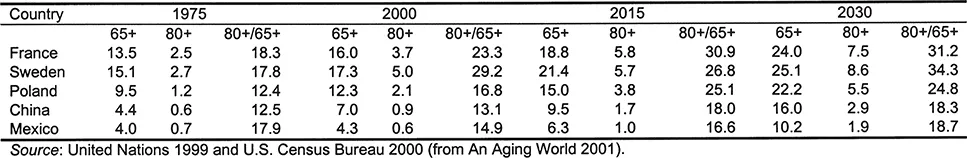

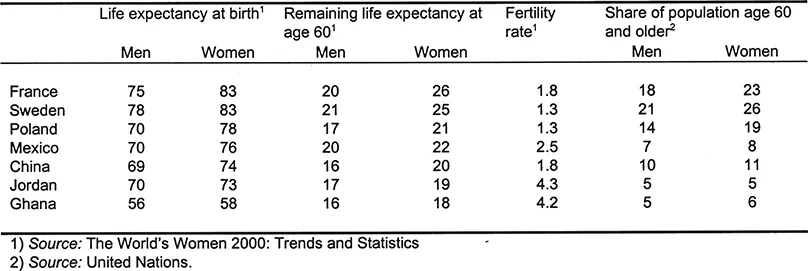

The support in old age is put under pressure in developing countries as well. They are aging rapidly as shown in table 1.1. Aging is caused both by increases in life expectancy and decreases in fertility. These are shown in table 1.2. Urbanization and changing family patterns break the former extended family- or village-based support systems and make these informal security systems less reliable. Also, the spread of HIV/AIDS might impact the sustainability of family ties. As a result, reliance on public arrangements to provide adequate retirement income is going to increase.1 Most developing countries have public social security systems although these schemes are far less important than existing family-based systems.

To introduce or reform existing formal, mandatory systems in developing countries poses additional challenges. The introduction of an earnings-related pension scheme requires a well-organized infrastructure that can support tasks such as: the collection of contributions, recording of earnings and paying of benefits. Furthermore, the exchange of informal systems for an extended, formal, mandatory system may not solve the problem of poverty in old age. A mandatory system means restrictions are put on possible lifetime consumption patterns. In low-income groups such restrictions are likely to be binding, forcing people to a low level of consumption when young which creates a reverse incentive to continue working under the prior informal system and might actually be a contributory cause as to why the informal economy is so important in these countries. A weak connection between contributions and benefits further worsens the dilemma. For these countries it may, therefore, as a first step, be better to introduce a flat-rate minimum pension benefit to alleviate poverty in old age. However, although the challenges differ, the need to review and consider pension reforms is important to both the developed and the developing world.

We may, thus, conclude reforming the systems of support in old age has to be given top priority. In this essay we analyze different ways of organizing pension systems. We give the pros and cons of the combinations of different features with special reference to gender aspects. An aspect of special interest here is men and women have different patterns of work history with women having a lower participation rate in the formal labor market, including interrupted careers in response to child rearing, as well as lower wages in general. Also, women have longer life expectancy than men and more often become widows than men become widowers. These differences may influence the consumption possibilities in old age depending on how the pension system is designed. Pension benefits will reflect labor market behavior. However, it is important not to compensate for gender differences in the labor market in pension systems as that would merely reinforce traditional gender roles and preserve discrimination in the labor market.

We are specifically interested in: if one design favors women more than another and in what respect? The analysis will provide a basis for making decisions about pension reform.

First, we give an analytical overview on different designs and their effects on distribution. We then describe the pension systems in a number of countries trying to evaluate them by the taxonomy given.

The chapter is organized as follows: section 2 focuses on design features that are important to women’s pension benefits and rate of return on their contributions and how different pension rules create incentives for different behaviors for women compared to men. The following section 3 describes pension rules in China, France, Ghana, Jordan, Mexico, Poland and Sweden. For the developing countries we focus on urban workers as pension plans in rural areas are very limited. The features of these pension systems are analyzed with respect to their expected effects on pensions and rates of return for men and women in the selected countries. Section 4 highlights gender differences in the labor market. Section 5 concludes the chapter.

Table 1.1

Percent Elderly of Total Population, 1975, 2000, 2015 and 2030

Table 1.2

Life Expectancy, Fertility, and Share of Population Age 60 and Older

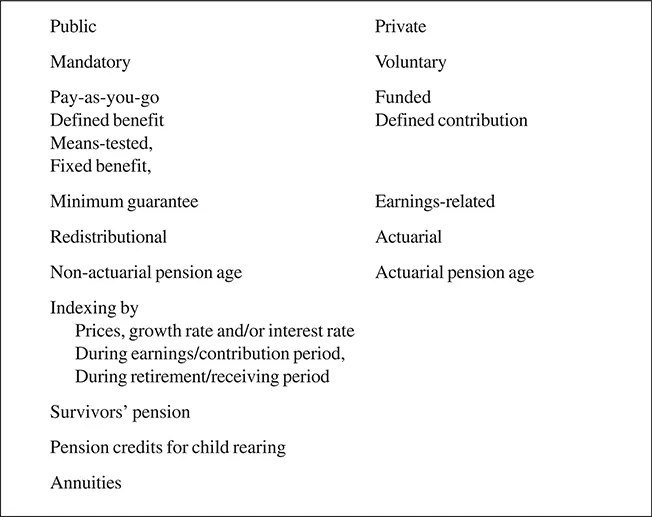

Public-Private

In the debate public-private is often confused with the mandatory-voluntary dichotomy, implicitly assuming that a public system is mandatory and a private one voluntary. But nothing prevents a public system from being voluntary or a mandatory system from being handled by the private sector. In fact, a number of examples show this.

The choice between public and private administration is a question of efficiency. For example, competition between companies in the private sector improves efficiency however, advertizing costs may be high thus reducing the gains from competition. Comparatively, public systems are usually uniform, i.e. not differentiated according to costs/risks. This being the case, a system that does not differentiate between different risk groups has to be mandatory as the premium of the insurance is set to reflect the risk of average individual; in this case of a pension system to the risk of an individual’s living a long life. Contrarily, if such a system was voluntary, only individuals who expect to live longer than average would buy the insurance. As a result, by its nature a mandatory pension system redistributes income to individuals with longer than average life expectancies. Besides being efficient, uniform systems cost less than differentiated systems as risk dispersion information is not needed.

Private systems can, of course, also be uniform as long as they are mandatory. However, the raison d’être for a private company is to make profit. Differentiating premiums and benefits in accordance with risk differences, i.e. making the insurance actuarial, seems to be one way of doing this. However, public systems may also be actuarial.

In the face of the problems the pay-as-you-go systems are up against due to aging, privatization is often called for as a remedy. Privatization is here often confused with increased funding which, again, can take place in a public as well as in a private system.

Political risk is often assumed to be smaller in a private system than in a public one. This risk is rather a question of transparency than which sector is handling the insurance. An unsustainable system, be it private or public, has to be reformed and a restricted number of parameters can be used for this purpose. In a private system the claims are protected by a formal contract that might have to be renegotiated. In a public system, especially a pay-as-you-go system, the claims are protected by an (implicit) social contract between generations. Either of them can, and sometimes has to be, changed.

The choice of public-private in itself does not have any gender effect.

Mandatory-Voluntary

A mandatory system forces people to save for old age, particularly those who might otherwise be too short-sighted to save on their own. Another reason for mandatory pensions is to avoid free-riders. This group may be destitute in retirement because of the lack of savings with tax payers having to support them.

In a voluntary system, premiums or annuities have to be differentiated in accordance with risk; otherwise low risk individuals will find it profitable not to join the insurance. That is, individuals who think they have shorter than average life expectancies will not join the insurance. If there is asymmetric information (the seller and the buyer not having the same information on risk) the insurance market may not be able to differentiate in accordance to risk and may not reach an efficient solution (Arrow 1974, Barr 1998). A solution to this problem is to make the system mandatory. When risks (risks vary according to sex, health, region etc) in different groups are known; i.e. when it is possible to differentiate the premiums or annuities, no efficiency reasons exist to make the system mandatory. However, if the intention is to have a common risk pool of men and women, then the system has to be mandatory. If the premiums are the same for men and women, they will be set to reflect women’s longer life expectancy. This means men, on average, will pay more into the system than they receive in benefits and, therefore, will not join. In this respect a mandatory system favors women since life expectancy of women is higher than that of men.

If the system is to be used for redistribution, it has to be mandatory.3

A mandatory system poses a restriction on the choice of consumption profile over a lifecycle by delaying some consumption until old age. This restriction is more likely to be binding in low-income groups than for high-inco...