Chapter 1

Quality counts

Why a concern for understanding?

At a time when an institution's place in the league tables can be everything, examination grades matter. Who can blame the hard-pressed teacher who, like some latter-day Mr Gradgrind, crams in the facts? Some may see this as the whole point of going to school or all that is achievable in the circumstances. It cannot be denied that knowing some facts and routines is useful but simply adding more is not everything. Collecting information is easy today but understanding it is what really matters. It is not so much the quantity of learning which makes a difference but its quality, how well it is digested and how well it hangs together in ways which we can use to guide what we do in new situations. Understanding may also change our minds, make us less gullible, and let us see other points of view. But none of this comes free, either for the teacher or the learner. It takes effort and time so it is not surprising that understanding can slip into the background.

Many of our daily thoughts and tasks do not call for understanding. For instance, there is no need to understand knots to fasten a shoe lace. Some situations simply repeat themselves and the same response is effective without understanding. But we are often faced with situations that are not like those we have met before. Illness, for instance, varies enormously. How are its symptoms to be interpreted and the illness treated? A kind of knowing that enables a flexible response is what is needed. Knowing what literally understands illnesses has the potential to do that. Halford (1993) has put it in broader terms: understanding offers a cognitive autonomy that helps to free its owner from the inflexible act, from domination and from exploitation. Of course, not all understanding serves a material or practical end: Luke (1996) found himself richer for understanding events like the rising of the sun and how it supports life. Understanding is an economical way of knowing which captures innumerable particulars about the world and reduces them to a coherent, manageable and even satisfying order. We should pursue it with vigour.

‘Doesn't everyone teach for understanding?’ a colleague once asked. Some do, some think they do, and others frequently do not. This book is about how to support understanding in both children and adults. It is for any teacher, experienced or otherwise, who wants learners to do more than reproduce what they have been told.

A thumbnail sketch of some underlying ideas

We all have a natural tendency to try to make sense of the world because knowing what to expect the next time we meet something has survival value (Mithen, 1996; Wolpert, 2003). But this does not mean that the sense we make is exactly like the sense someone else makes. One small boy, having heard the word ‘disciple’, later recycled it as ‘icicle’. Making something meaningful is a very personal thing. We make links between bits and pieces of information until it makes some kind of sense, at least to us. E.M. Forster's epigraph for Howards End is about making connections. The prize is the greater meaning that can flow from the union of isolated thoughts. All it takes is a connection but making it may not be easy. These connections cannot be passed or transmitted from one person to another, learners have to make them themselves. When it results in new connections which the person did not have before, such productive thought is truly creative. On occasions, the created products may also be new to the world and widely valued and, in due course, they may even appear in textbooks for the next generation to re-create for themselves. But, where there are connections to be made, the mental effort has to be supplied by the learner. Fortunately, the process can be supported. In order to talk of supporting understanding, there needs to be some idea of what understanding means. Unfortunately (or interestingly, according to your point of view) understanding refers to a variety of mental conditions and can mean different things in different contexts. This book begins with a basis for an understanding of understanding then it shows how understanding may be supported in diverse contexts.

In Britain, as in many other parts of the world, teachers’ classroom skills largely grow from experience of being taught, watching others teach, and trying to teach. When such experience is sound and when learners and expectations of the teacher change only slowly, if at all, this can work – up to a point. But when these change, the old skills can let the teacher down. Such teaching lacks a basis or a pedagogy which informs the development of new practices (Simon, 1999; Alexander, 2009). In other words, teachers themselves need to understand what good teaching is and what makes a good teacher. In the past, educational psychology has revealed little that was not obvious. For instance, experience soon shows that repetition helps memorization and today's lesson is more likely to be recalled than yesterday's lesson. Similarly, experiments with rats said little about how to help people grasp the meaning of a work of art, a scientific theory or a historical event. More recent developments in psychology, however, have much more to offer. From one perspective, the mind is a little like a library. It behaves like a huge repository for knowledge just as a library is a huge store for books. In the library, books may be taken from the shelves and sorted on a table. If there is room on the table, recent acquisitions may be added, integrated with other books and taken to appropriate shelves for storage. The mind behaves as though it has a working space that serves as its table top. Just like a table, it has a limited capacity. New information may be routed to the working space. Existing knowledge may already be there or be taken from the long-term store and added to it. If there is enough mental capacity, the information and knowledge could be organized, related, integrated, used and returned to the store. Not all new information or new organizations are worth keeping and much may be discarded. Some, however, find their way to the mental shelves and may be taken down and used later. The mind's repository has an enormous capacity but its table, where it does its organizing, relating and integrating, is tiny in comparison. We need to use its space efficiently if we are to relate elements of information and construct understandings of it. It can help if information is presented to us in some organized way, if we have relevant information to hand, and if we have a degree of facility in handling it. Of course, the mind's activity is not confined to its table top and a lot goes on of which we are not aware. In formal education, we usually want learners to reflect on and verbalize their understandings but unconscious mental activity cannot be ignored as it contributes significantly to the conscious processes.

Putting together some inkling of the nature of understanding and ideas about how the mind handles them has led to testable ideas about what might support understanding. As the aim here is to provide a practical framework for supporting understanding, I have drawn on a variety of ideas with the potential to foster understanding in a wide range of learners. Cognition may be modelled in various ways. Just as a house may be described in terms of its rooms and their function, there are micro or macro models of cognition. The library analogy is an example of a macro model. But, at a micro or molecular level, the house may also be described in terms of its bricks and mortar. In the same way, cognition may be modelled by complex networks of interacting units that, some argue, resemble the activity of brain cells (Bechtel and Abrahamsen, 1991; Hill, 1997). For practical purposes, however, macro models of cognition are very useful as they can be applied more or less immediately to the kinds of mental activities that are relevant to understanding (Baddeley, 1993). They largely underpin the explanations offered in this book. Nevertheless, readers may need to remind themselves that such models are only models; they do not necessarily imply that the brain is physically constructed like the model.

Direct support for making mental connections between ideas is, of course, only a part of the picture. Some learners have to be persuaded that what is expected of them is worthwhile otherwise they may not try to understand. Others may not know what counts as understanding. Still others need to learn how to make the best of their thinking so that they can function as independent learners. Even when learning seems to be going well, there is the inescapable fact that no one knows what is in someone else's mind. This means that ways of gauging the quality of learning have to be found. These illustrate that the total learning environment has several components and these components can interact and bear upon the quality of learning. They are not simply additional features that can be ignored in moving from ideas about understanding to ideas about instruction (Hargreaves, 1986; Sternberg, 1986).

The structure of the book

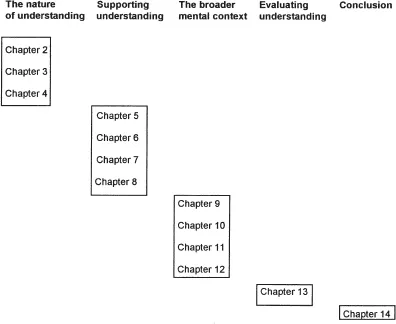

You will not be surprised to find that I think the best way to approach this book is to read it from the beginning through to the end and in the order presented. Nevertheless, recognizing that readers have different interests and needs, other routes through the book are possible. Figure 1.1 shows the structure. Each column represents a more or less self-contained group of chapters and each group might serve as a starting point for a particular interest. The first block is about the value of understanding, what understanding means in different contexts, and understanding as constructing mental relationships. The second block describes mental engagement for understanding and what fosters it, a framework for supporting understanding and the use of analogies, the support provided by surrogate teachers such as textual materials and information technology, and understanding failure. The third block relates to the variety of factors that bear upon a person's learning behaviours, conceptions of understanding, motivation, and self-regulated learning. The final chapters deal with evaluating and assessing understanding and bring various threads together. Most chapters begin with a brief overview and end with a summary and there is a short glossary to help those who prefer to dip into the book. Each chapter ends with an Afterthought which some readers might like to reflect on.

Figure 1.1 A schematic diagram showing the structure of the book

Although not infallible, understanding is a very powerful way of relating to the world. When it slips into the background because examination results and league tables matter more or through lack of time, indolence or ignorance, the loss for each learner could be considerable. Understanding can make learning more durable and more valuable for the learner. It is worth pursuing as a means to an end and as an end in itself.

Afterthought

It's commonly said that if you really want to understand something, teach it. What's teaching got to do with it?

Further reading

While I argue that understanding is a very significant aim of education, there is a broader context, see, for example, R. Marples (1999) The Aims of Education, London: Routledge. Aims of education at any level can be subverted by external and internal forces, see, for instance, K. Farber (2010) Why Great Teachers Quit, London: Sage, and J.C. Knapp and D.J. Siegel (2009) The Business of Higher Education, Volume 3: Marketing and Consumer Interests, Santa Barbara: Greenwood.

Chapter 2

Understanding: a worthwhile

goal

Overview

That understanding is a good thing seems self-evident. Like many things that are self-evident, the reasons are not always made explicit, so some are mentioned here. Given that understanding can be worthwhile and is a requirement of many programmes of study, how can it become a secondary concern? The teaching and learning situation is complex and teachers can be faced with contradictory demands.

What does understanding offer?

We want students to learn. At times, it may be sufficient for them to memorize something and recall it on demand but, at other times, they should understand. Understanding is often assumed to be a good thing and potentially worth more than memorization. Yet, learning things off by heart is often easier and quicker than understanding them. So is understanding worth the effort? What does it have to offer?

First, understanding can satisfy a number of personal needs. For instance, we often feel dissatisfied with merely knowing that event B followed event A. What we are curious about is why B followed A. The historian, Henry Adams, said he did not care what happened, he wanted to know why it happened (Miller, 1996). The questions that arrive on editors’ desks of popular journals such as the New Scientist show a similar inclination (for example, why do boomerangs come back? Why is it more difficult to swim in a pool that is very full?). Ultimately, knowing why things are as they are or happen as they do can help us relate to the world, both natural and physical (Davalos, 1997). Laurie Lee recollected what not understanding was like when, as a child, he found himself alone and surrounded by an incomprehensible, unpredictable world of nature: it made him howl in terror (Lee, 1959). That is not to say that the understanding which helps us relate is always correct, final, absolute or an exact match for someone else's understanding. What it does do, however, is serve the function of giving order to our mental world and of dispelling chaos from it so we can function effectively in the real world.

Second, understanding can facilitate learning. For instance, Hawkins and Pratt (1988), teaching one Christmas in New Zealand, noticed that traditional Christmas cards are potentially meaningless to 9- and 10-year-old New Zealanders. Christmas for them is warm, blue and gold – and without robins. They realized that a teacher cannot assume that the conventional signs and symbols on such cards evoke the same meaning for the child as for the teacher. Adults may take an understanding of them for granted. In the belief that learning is more efficient when reasons are known, they explained this pictorial, cultural shorthand and saw a better grasp of the meanings of Christmas. In the USA, Hiebert and Wearne (1996) carried out a longitudinal study of children learning mathematics as they moved through grades 1 to 4 (6 to 9 years). They were able to show that understanding place value and multidigit addition and subtraction facilitated the invention and modification of ways of solving arithmetical problems. The instruction was not concerned with teaching algorithms but focused on, for example, quantifying sets of objects, examining ways of representing quantities (orally, writing numbers, using objects). Children were encouraged to develop their own procedures and explain them to other children. Underpinning the approach was a belief that children are more likely to understand if they have the chance to construct relationships themselves. One assessment task for the youngest children was to deduce how many teams of 10 players could be made from 64 children. Interviews checked for an understanding of the procedures the children used. Hiebert and Wearne found that understanding helped children make sense of instruction about procedures that came later. There was increased retention and progress was generally more rapid for those who had shown understanding and it also helped the children choose more efficient procedures. When an algorithm was not known, those who understood could often find a solution themselves. Hiebert and Wearne concluded that understanding has real value in enhancing and facilitating learning. But note that, at least in mathematics, this does not mean that understanders will necessarily obtain more correct answers than non-understanders – non-understanders can be quite proficient in using an algorithm. The facilitation is in the speed of learning new procedures, in the flexible use of knowledge in novel situations and in the retention of the learned material. Further support for this conclusion is in Winkles’ (1986) study of the learning of trigonometry amongst 14-year-olds. He compared an ‘achievement’ group with an ‘achievement with understanding’ group. Again, there was evidence of an enhanced ability to think flexibly in the understanding group when dealing with novel problems. In a very different context, Minnaert and Janssen (1992) have also demonstrated the role of understanding in facilitating further learning in their university students of psychology in Belgium.

Third, understanding does not just facilitate further learning, it can also make someone want to learn more (and, conversely, be frustrating when it is absent). Some thoughts on the value of understanding describe a girl's behaviour when she had to memorize the oath Greek boys took 2500 years ago. She saw the oath as meaningless and irrelevant. But when its meaning was explained, she willingly engaged with the task (G.A.B., 1933). Engaging students in learning can, at times, be difficult. Every subject has its disenchanted students who avoid it when they can. An Australian study of children's classroom behaviours found that when learners felt they were developing an understanding of a topic, their engagement increased (Darby, 2005). A teacher who consistently and successfully helps children understand could find that they come back for more.

Fourth, a capacity to respond flexibly in different situations is a valuable one to have. Diagnosing an illness, finding a fault in an electrical circuit, responding to developments in the marketplace or in relationships between people, for instance, can all benefit ...