1

EXPERIMENTAL BODY IMAGE RESEARCH

Approaching the experimental body image literature, the sheer weight of knowledge at first seems both overwhelming and impenetrable. The experimental body image literature describes hundreds of controlled experiments, producing empirical evidence about body image and women’s body image problems. A closer examination of this research reveals that its knowledge claims about women’s bodies are mainly based on fundamental assumptions that are problematic for the women whom body image researchers would claim to be helping.

The phrase ‘body image research’ misleadingly suggests a comprehensive body of work founded on agreed-upon ontological and epistemological assumptions. In fact, definitions of body image vary greatly and stem from a range of different theoretical orientations, including phenomenology, neurology, experimental psychology, psychoanalysis and feminist philosophy. The focus of my work is on the effect of one important segment of this varied research – the use of the concept of body image in experimental psychology. My interest in this area of body image work stems from its significant social and cultural influence. I argue that scientific psychology’s conceptualisation of body image and its ‘disturbances’ powerfully informs – indeed, forms – contemporary common-sense and popular understandings of the body.

The aim of this chapter is to provide a detailed description of a representative selection of experimental psychological research1 on body image, identifying key researchers, the psychological concepts and methods they utilise, and some of the assumptions underpinning their methods. A critique of this research follows in Chapter 2, which focuses on the potential effects of psychology’s constitution of women’s bodies in body image research.

Historical precursors

One of the first academic psychologists to investigate body image and body perception was the North American psychologist Seymour Fisher (Fisher and Cleveland, 1958). Although only Fisher’s more recent (1986) work is cited by contemporary experimental researchers, his writings about body image span four decades. Fisher’s stance is an unusual mix of a psychoanalytic (Freudian) view of body image combined with a commitment to experimentally validated knowledge. Fisher chastised his contemporaries from the late 1950s onwards, particularly behavioural psychologists, for only paying ‘lip-service to the fact that each person is a biological object’ and therefore ‘regarding people as disembodied’ (Fisher, 1986: xiii). For him, understanding human behaviour depended upon knowledge about ‘body perception’ – people’s feelings and attitudes towards their bodies: ‘I firmly believe we will eventually find that measures of body perception are among our most versatile predictors of how people will interpret and react to life situations’ (Fisher, 1986: xii).

In 1969 Franklin Shontz, anticipating some of the themes of current research, published a series of studies about body-size judgements. He noted that generally people are less accurate in perceiving the width of their own bodies or body parts than the size of ‘non-body objects’. Shontz, like Fisher, considered that the perception of body size was important to experimental psychology. Like Fisher, he also assumed the body was an object, objectively separate from the person doing the judging and able potentially to be perceived in the same way as objects that are not bodies.

Shontz asserted that there are measurable (gender-differentiated) ‘patterns of over- and under-estimation’ that apply to specific areas of the body. He claimed that women usually overestimate the width of their waists more than men do. He attributed this ‘mistake’ to women’s ‘concern over conforming to American standards of feminine beauty, which required a small waist as strongly as they do an ample bust’ (Shontz, 1969; cited in Fisher, 1986: 163).

Prior to Fisher’s work, Sidney Secord and Paul Jourard (1953), working in personality theory, emphasised ‘the individual’s attitudes towards his body’ as being of ‘crucial importance to any comprehensive theory of personality’ (Secord and Jourard, 1953: 343). These researchers believed that the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with one’s body was quantifiable as ‘body-cathexis’. They produced ‘The Body Cathexis Scale’ in order to measure it. Almost a half century later, the scale is still used in experimental body image research to ‘... assess the more complex representations of physical appearance’ (Thompson, 1990: 15). Secord and Jourard tied body cathexis to self-concept, claiming that ‘valuation of the body and the self tend to be commensurate’ (Secord and Jourard, 1953: 346). Low scores for body cathexis were linked with negative personality traits.

In a seminal study of body perception within experimental psychology, Traub and Orbach (1964) investigated visual perception of the physical appearance of the body. They designed an adjustable full-length mirror which could ‘reflect the body of the observer on a distortion continuum ranging from extremely distorted to completely undistorted’. The task for the subject was to adjust his/her reflection until it ‘appears undistorted’ or ‘... so that it looks just like you’. Traub and Orbach were concerned with the distorting effects of the mind on perception, or the ‘confounding of direct perception of the physical appearance of the body with those thoughts, images, attitudes and affects regarding the body’ (Traub and Orbach, 1964: 65). The implicit assumption in these studies was that the mind should ideally be able to perceive the objective body more or less accurately.

There are several epistemological features of the work of these early researchers worth highlighting, since they introduce themes and a framework for understanding the notion of ‘body image’ which has provided the foundation for recent psychological research. The body is viewed as an object of perception objectively separate from the mind of the person doing the perceiving. It is assumed that the body can be perceived accurately or inaccurately. Failure to ‘accurately’ perceive one’s body ‘as it really is’ is understood to be the result of a perceptual or cognitive disturbance within the individual. Implicit in this analysis is the idea of the norm. It is assumed that there is a ‘correct’ way of perceiving the body, and that failure to do so is indicative of pathology, specifically a ‘disturbance’ in ‘body image’.

Body image disturbance and the place of perception

The work of German psychiatrist Hilde Bruch in 1962, on eating disorders, had the effect in the following decades of focusing body image research on disturbance. Bruch worked predominantly with young women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Her observations led her to conclude that ‘What is pathognomic of anorexia nervosa is not the severity of the malnutrition per se ... but rather the distortion in body image associated with it: the absence of concern about emaciation’ (Bruch, 1962: 189). Bruch hypothesised an underlying perceptual ‘disturbance’ which meant that anorexic girls saw their ‘gruesome appearance’ as ‘normal or right’ (Bruch, 1962: 187). She asserted that there was ‘a disturbance in body image of delusional proportions’ present in all patients, which she regarded as an important diagnostic and prognostic sign of anorexia nervosa (Bruch, 1962: 191).

The main significance of Bruch’s work for experimental body image research is her influence on researchers such as Slade and Russell. These researchers, whose work became widely cited in this field, aimed to link perception of body size with eating disorders. In 1973 they carried out a series of studies of ‘the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa’. They considered the research to be important not only in establishing the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa but also in elucidating ‘the pathogenesis of this puzzling illness’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 188).

Slade and Russell’s emphasis on objective experimental methodology reinforced this approach as crucial to doing body image research. Twenty-five years later, others such as Thompson (1990) have been explicit:

In recent years, attempts have been made to manipulate variables in the laboratory and measure the effects on body image indices. These laboratory models of disturbance are of critical importance to the body image field because they demonstrate with the strictest empirical controls the factors that may operate in natural settings to cause body image disturbance.

(Thompson, 1990: 51–2)

As Slade and Russell’s work epitomises research with such ‘strict empirical controls’ – an approach which has come to almost completely dominate the research area – it is worth describing their experimental method in detail.

The aim of Slade and Russell’s first study (1973) was to try to measure how women with anorexia nervosa perceive their body size. Their study compared 14 anorexic patients with 20 ‘normal female controls’, mainly postgraduate psychology students, to test the hypothesis that the anorexic patients would significantly overestimate their size in relation to the control group. Slade and Russell’s ‘objective method... for measuring body image perception’ was ‘the size estimation task’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 190). This task involved the subjects estimating the width across four parts of their body; the face, the chest, the waist at the narrowest point and the hips at the widest point. These measures of ‘perceived size’ were obtained by a ‘visual size estimation apparatus’, which consisted of a movable horizontal bar mounted on a stand. Two lights attached to runners were mounted on tracks set into the horizontal bar. A pulley-device was set up so that when one of the lights was moved outwards (or inwards) from a central point, the other light moved outwards (or inwards) in the opposite direction by the same amount. At the rear of the horizontal bar a measuring instrument was attached, so that the distance between the lights could be noted. Measures of ‘real size’ of the women’s bodies were ascertained by the use of an anthropometer – a body-measuring device. The experiments took place in a darkened experimental room and at no time was the subject informed of the results of her estimates. The measurements were obtained from the subjects while wearing their normal clothes ‘... in order to provide the most natural situation for studying body image perception’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 190).

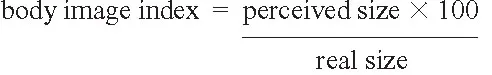

After gathering the data from the 34 subjects, Slade and Russell devised a formula referred to as the ‘body-image perception index’ (BPI), which they calculated as follows:

Using this index, a value of 100 corresponds to ‘accurate perception’ of body size. A value of less than 100 shows that physical size is underestimated, and a value greater than 100 shows that physical size is overestimated.

Slade and Russell used the mean indices (BPI) for the two groups of women in this study to claim that ‘while normal women tend to be remarkably accurate in their body-size estimations, patients with anorexia nervosa exhibit fairly large distortions’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 192). The authors interpreted overestimation of body width on this task as evidence of ‘body image distortion’. Further, Slade and Russell noted that the four perception indices for both groups of subjects showed positive and significant intercorrelations. They claimed as a result that ‘... there is a general factor of body image perception which is observable in both anorexic patients and normals’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 191–2). Their research concretised ‘body image perception’ as a construct which could be both observed and measured, and could indicate some pathology.

Slade and Russell (1973: 192) also investigated the association between ‘body width perception’ and ‘perception of non-body objects’. This experiment was based on the assumption that ‘women’s bodies’ are a stable entity, similar to other inanimate objects. The aim of the experiment was to ascertain whether the (in)ability of individual women accurately to estimate the width of their bodies extended to estimations of the width of non-body objects. If a woman was able accurately to perceive the width of non-body objects (e.g. a vase) then her inability objectively to perceive the width of her own body could not be explained by a ‘general perceptual disturbance’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 193).

According to Slade and Russell, anorexic women did not over-estimate the sizes of non-body objects (10 inch and 5 inch wooden blocks) but they ‘misperceived’ their own body size. Consequently, they claimed that their studies were in line with Bruch’s description of body image as part of the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa. They argued that they had provided ‘a simple means of identifying and measuring this perceptual disturbance’. They had offered ‘... understandings of the causation of anorexia nervosa [and] the pathological mechanisms operating in this illness’ (Slade and Russell, 1973: 197).

Slade and Russell’s (1973) claim to have identified ‘a general factor of body image perception’ and a way of measuring it encouraged further experimental research into body size perception, particularly with groups of women diagnosed as ‘eating-disordered’. The notion of a ‘perceptual disturbance’ as the cause of ‘body image disturbance’ was uncritically accepted and much of the research that followed focused on inventing methods that would measure that disturbance.

Slade and Russell noted that the concept of body image was ‘vague and ill-defined’. The definition they used, still in use today (see e.g. Slade, 1994), was taken from Paul Schilder, the German neuropsychologist, whom they quoted as saying that body image is ‘the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say, the way in which the body appears to ourselves’ (Schilder, 1935: 11; cited in Slade and Russell, 1973: 189).

Their selective use of Schilder’s work omits central features of his complex, theoretical model of the body image. Schilder’s conception of the body image owed more to psychoanalysis than neurophysiology. Freud’s work was an important influence, in particular his conception of libidinal energy and drives. For Schilder, social and interpersonal attachments and investments, as well as libidinal energy, shape a person’s self-image and conception of the body. Far from using an isolated image of the body, such as that employed by Slade and Russell (where a lone body is perceived within a ‘blank’ experimental space), Schilder’s model involves the relations between the body, the space surrounding it, other objects and other bodies. In his model the body image ‘is formed out of the various modes of contact the subject has with its environment through its actions in the world’ (Grosz, 1994: 85). In ‘borrowing’ one aspect of Schilder’s concept, Slade and Russell reduced his theory of the body image to a simple asocial mental representation of the body.

I was into all the depictions of popular culture, movies and literature. I wanted to be a lean, mean, healthy, competent machine, but also I was compelled because of my own sadness and wanting to hurt myself, what springs to mind is Heathcliff, Jane Eyre or some kind of wan heroine, romantic, I think I had that notion about that sickly part of me too. I felt quite sorry for myself and fancied myself as, and I was a bit, out on the moors alone. It didn’t seem right to be healthy and hearty if that was my persona or what I identified with. It’s a fine line when you tip over from being mean and lean to being sick and fragile. I even had different outfits to go with the different personas, the latest Lycra gym gear and then this long black coat I would wear.

Why did Slade and Russell adopt such a narrow and simplistic definition of body image? Schilder’s complex theory of body image rested on different epistemological and ontological assumptions, particularly in terms of the connection between the mind and body/reality, and was not amenable to experimental investigation. The assumptions of Russell and Slade and their reading of Schilder have been important in contributing to definitions of what can be said and thought about body image.

In the years since Slade and Russell (1973) established ‘body image disturbance’ as a construct, it has become officially recognised by the American Psychiatric Association. In 1980 it was included in the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The manual listed ‘Disturbance of body image, e.g. claiming to “feel fat” even when emaciated’ as the second of five necessary diagnostic criteria for anore...