- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Framer Framed brings together for the first time the scripts and detailed visuals of three of Trinh Minh-ha's provocative films: Reassemblage, Naked Spaces--Living isRound, and Surname Viet Given Name Nam.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Interviews

4 Film as Translation

A Net With No Fisherman*

DOI: 10.4324/9780203699416-4

MacDonald: You grew up in Vietnam during the American presence there. This may be a strange question to ask about that period, but I'm curious about whether you were a moviegoer and what films you saw in those years.

Trinh: I was not at all a moviegoer. To go to the movies then was a real feast. A new film in town was always an overcrowded, exciting event. The number of films I got to see before coming to the States was rather limited, and I was barely introduced to TV before I left the country in 1970. Actually, it was only when the first television programs came to Vietnam that I learned to listen to English. Here also the experience was a collective one since you had to line up in the streets with everyone else to look at one of the TVs made available to the neighborhood. I had studied English at school, but to be able to follow the actual pace of spoken English was quite a different matter.

M: Did you see French films in school?

T: No. A number of them were commercially shown, but during the last few years I was in Vietnam, there were more American than French films. My introduction to film culture is quite recent.

M: Reassemblage seems to critique traditional ethnographic movies—Nanook of the North, The Ax Fight, The Hunters ... I assume you made a conscious decision to take on the whole male-centered history of ethnographic moviemaking. At what point did you become familiar with that tradition? Did you have specific films in mind when you made Reassemblage?

T: No. I didn't. You don't have to be a connoisseur in film to be aware of the problems that permeate anthropology, although these problems do differ with the specific tools and the medium that one uses. The question of limit in writing, for example, is very different from that in filmmaking. But the way one relates to the material that makes one a writer-anthropologist or an anthropological filmmaker needs to be radically questioned. A Zen proverb says “A grain of sand contains all land and sea,” and I think that whether you look at a film, attend a slide show, listen to a lecture, witness the fieldwork by either an expert anthropologist or by any person subjected to the authority of anthropological discourse, the problems of subject and of power relationship are all there. They saturate the entire field of anthropological activity.

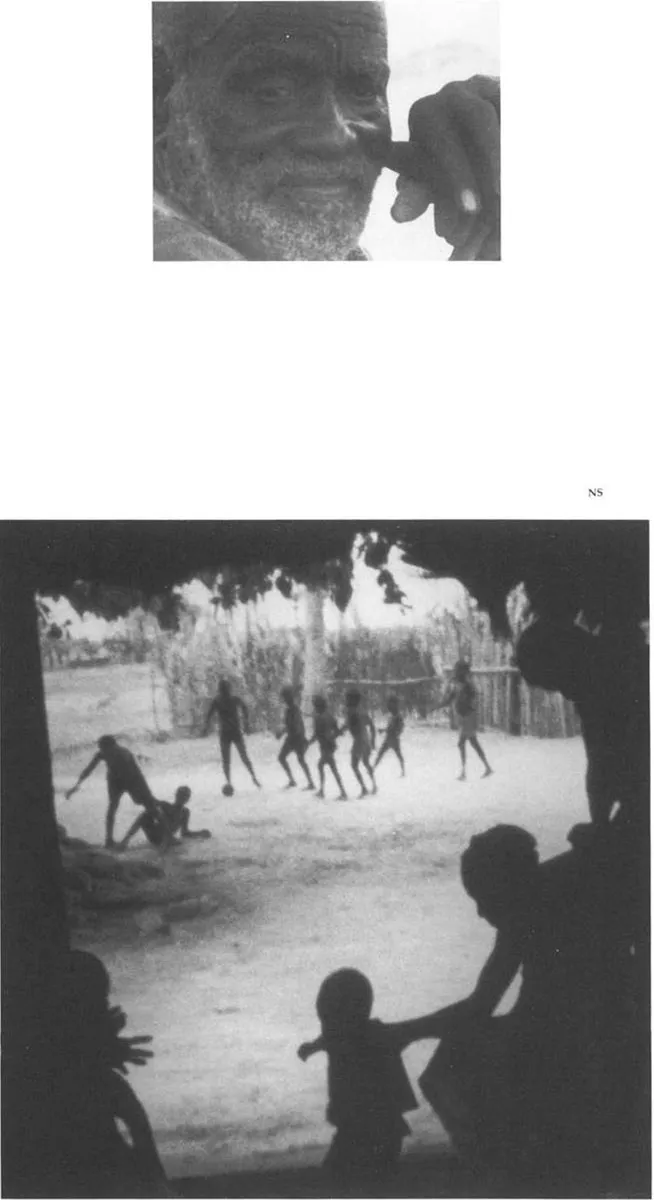

I made Reassemblage after having lived in Senegal for three years (1977–80) and taught music at the Institut National des Arts in Dakar; in other words, after having time and again been made aware of the hegemony of anthropological discourse in every attempt by both local outsiders and by insiders to identify the culture observed. Reassemblage was shot in 1981 well after my stay there. Although I had by then seen quite a number of films and was familiar with the history of Western cinema, I can't say this was a determining factor. I had done a number of super-8 films on diverse subjects before, but Reassemblage was my first 16 mm.

M: You mentioned you were looking at films before you went to Senegal. Were you looking at the way in which Senegal or other African cultures were portrayed in film?

T: No, not at all. Despite my having been exposed to a number of non mainstream films from Europe and the States at the time, I must say I was then one of the more passive consumers of the film industry. It was when I started making films myself that I really came to realize how obscene the question of power and production of meaning is in filmic representation. I don't really work in terms of influence. I've never been able to recognize anything in my background that would allow me neatly to trace—even momentarily—my itinerary back to a single point of origin. Influences in my life have always happened in the most odd, disorderly way. Everything I've done comes from all kinds of direction, certainly not just from film. It seems rather clear to me that Reassemblage did not come from the films I looked at, but from what I had learned in Senegal. The film was not realized as a reaction to anything in particular, but more I would now say, as a desire not to simply mean. What seems most important to me was to expose the transformations that occurred with the attempt to materialize on film and between the frames the impossible experience of “what” constituted Senegalese cultures. The resistance to anthropology was not a motivation to the making of the film. It came alongside with other strong feelings, such as the love that one has for one's subject(s) of inquiry.

M: So the fact that you found a film form different from what has become conventional as a means of imaging culture was accidental. . ..

T: Not quite accidental, because there were a number of things I did not want to reproduce in my work: the kind of omniscience that pervades many films, not just through the way the narration is being told, but more generally, in their structure, editing and cinematography, as well as in the effacement of the filmmakers, or the invisibility of their politics of non-location. But what I rejected and did not want to carry on came also with the making of Reassemblage. While I was filming, for example, I realized that I often proceeded in conformity with anthropological preoccupations, and the challenge was to depart from these without merely resorting to self-censorship.

M: Often in Reassemblage there'll be an abrupt movement of the camera or a sudden cut in the middle of a motion that in a normal film would be allowed to have a sense of completion. Coming to the films from the arena of experimental moviemaking, I felt familiar with those kinds of tactics. Had you seen much of what in this country is called “avant-garde film” or “experimental film?” I'm sorry to be so persistent in trying to relate you to film! I can see it troubles you.

T: [Laughter] I think it's an interesting problem because your attempt is to situate me somewhere in relation to a film tradition, whereas I feel the experimentation is an attitude that develops with the making process when one is plunged into a film. As one advances, one explores the different ways that one can do things without having to lug about heavy belongings. The term “experimental” becomes questionable when it refers to techniques and vocabularies that allow one to classify a film as “belonging” to the “avant-garde” category Your observation that the film foregrounds certain strategies not foreign to experimental filmmakers is accurate, although I would add that when Reassemblage first came out, the experimental/avantgarde film world had as many problems with it as any other film milieus. A man who has been active in experimental filmmaking for decades said for example, “She doesn't know what she's doing.”

So, while the techniques are not surprising to avant-garde filmmakers, the film still does not quite belong to that world of filmmaking. It differs perhaps because it exposes its politics of representation instead of seeking to transcend representation in favor of visionary presence and spontaneity which often constitute the prime criteria for what the avant-garde considers to be Art. But it also differs because all the strategies I came up with in Reassemblage were directly generated by the material and the context that define the work. One example is the use of repetition as a transforming, as well as rhythmic and structural, device. Since the making of the film, I have seen many more experimental films and have sat on a number of grant panels. Hence I have had many opportunities to recognize how difficult it is to reinvent anew or to defamiliarize what has become common practice among filmmakers. It was very sad to see, for example, how conventional the use of repetition proved to be in the realm of “experimental” filmmaking. This does not mean that one can no longer use it, but rather that the challenge in using it is more critical.

I still think that repetition in Reassemblage functions very differently than in many of the films I have seen. For me, it's not just a technique that one introduces for fragmenting or emphasizing effects. Very often people tend to repeat mechanically three or four times something said on the soundtrack. This technique of looping is also very common in experimental music. But looping is not of any particular interest to me. What interests me is the way certain rhythms came back to me while I was traveling and filming across Senegal, and how the intonation and inflection of each of the diverse local languages inform me of where I was. For example, the film brought out the musical quality of the Sereer language through untranslated snatches of a conversation among villagers and the varying repetition of certain sentences. Each language has its own music and its practice need not be reduced to the mere function of communicating meaning. The repetition I made use of has, accordingly, nuances and differences built within it, so that repetition here is not just the automatic reproduction of the same, but rather the production of the same with and in differences.

M: When I had seen Reassemblage enough to see it in detail, rather than just letting it flow by, I noticed something that strikes me as very unusual. When you focus on a subject, you don't see it from a single plane. Instead, you move to different positions near and far and from side to side. You don't try to choose a view of the subject; you explore various ways of seeing it.

T: This is a great description of what is happening with the look in Reassemblage, but I'll have to expand on it a little more. It is common practice among filmmakers and photographers to shoot the same thing more than once and to select only one shot—the “best” one—in the editing process. Otherwise, to show the subject from a more varied view, the favored formula is that of utilizing the all-powerful zoom or curvilinear travelling shot whose totalizing effect is assured by the smooth operation of the camera.

Whereas in my case, the limits of the looker and of the camera are clearly exposed, not only through the repeated inclusion of a plurality of shots of the same subject from very slightly different distances or angles (hence the numerous jump-cut effects), but also through a visibly hesitant, or as you mentioned earlier, an incomplete, sudden and unstable camera work. (The zoom is avoided in both Reassemblage and Naked Spaces, and diversely acknowledged in the more recent films I have been making.) The exploratory movements of the camera—or structurally speaking, of the film itself—which some viewers have qualified as “disquieting,” and others as “sloppy,” is neither intentional nor unconscious. It does not result from an (avant-garde) anti-aesthetic stance, but occurs, in my context, as a form of reflexive body writing. Its erratic and unassuming moves materialize those of the filming subject caught in a situation of trial, where the desire to capture on celluloid grows in a state of non-knowingness and with the understanding that no reality can be “captured” without trans-forming.

M: The subject stays in its world and you try to figure out what your relationship to it is. It's exactly the opposite of “taking a position”: it's seeing what different positions reveal.

T: That's a useful distinction.

M: Your interest in living spaces is obvious in Reassemblage and more obvious in Naked Spaces. You also did a book on living spaces.

T: In Burkina Faso, yes. And in collaboration with Jean-Paul Bourdier.

M: Did your interest in living spaces precede making the films or did it develop by making them?

T: The interest in the poetics of dwelling preceded Reassemblage. It was very much inspired by Jean-Paul, who loves vernacular architecture and has been doing relentless research on rural houses across several Western and non-Western cultures. We have worked together as a team on many projects.

Reassemblage evolves around an “empty” subject. I did not have any preconceived idea for the film and was certainly not looking for a particularized subject that would allow me to speak about Senegal. In other words, there is no single center in the film—whether it is an event, a representative individual or number of individuals in a community, or a unifying theme and area of interest. And there is no single process of centering either. This does not mean that the experience of the film is not specific to Senegal. It is entirely related to Senegal. A viewer once asked me, “Can you do the same film in San Francisco?” And I said, “Sure, but it would be a totally different film.” The strategies are, in a way, dictated by the materials that constitute the film. They are bound to the circumstances and the contexts unique to each situation and cultural frame.

In the processes of emptying out positions of authority linked to knowledge, competence and qualifications, it was important for me in the film to constantly keep alive the question people usually ask when someone sets out to write a book or in this case, to make a film: “A film about Senegal, but what in Senegal?” By “keeping alive” I mean, refusing to package [a] culture, hence not settling down with any single answer; even when you know that each work generates its own constraints and limits. So what you see in Reassemblage are people's daily activities: nothing out of the ordinary; nothing “exotic”; and nothing that constitutes the usual focal points of observation for anthropology's fetishistic approach to culture, such as the so-called objects of rites, figures of worship and artifacts, or in the narrow sense of the terms, the ritualistic events and religious practices. This negation of certain institutionalized cultural markings is just one way of facing the issues that such markings raise. There are other ways. And while shooting Reassemblage, I was both moved by the richness of the villagers’ living spaces, and made aware of the difficulty of bringing on screen the different attitudes of dwelling implied without confronting again and differently what I have radically rejected in this film. This was how the idea of making another film first appealed to me. Naked Spaces was shot three years later across six countries of West Africa, while Reassemblage involved five regions across Senegal.

M: Reassemblage takes individual subjects—people, actions, objects—and provides various perspectives on them; Naked spaces enlarges the scope but uses an analogous procedure. You deal with the same general topic—domestic living spaces—and explore its particular manifestations in one geographic area after another. And the scope of the view of particular spaces is enlarged too: you pan across a given space from different distances and angles (in Reassemblage the camera is generally still, though you filmed from different still positions). There's a tendency to move back and forth across the space in different directions to rediscover it over and over in new contexts.

T: The last description is very astute and very close to how I felt in making Naked Spaces. Although I would say that the procedure is somewhat adverse (even while keeping a multiplicity of perspectives) rather than analogous to the one in Reassemblage, the immediate perception is certainly that of an enlarged scope; physically speaking, not only because of the way the film works on duration and of the variety of cultural terrains it traverses, but also because, as you point out, of its visual treatment. In Reassemblage, I avoided going from one precise point to another in the cinematography. I was dealing with places and was not preoccupied with depicting space. But when you shoot architecture and the spaces involved, you are even more acutely aware of the limit of your camera and how inadequate the fleeting pans and fractured still images used in Reassemblage are, in terms of showing spatial relationships.

One of the choices I made was to have many pans; but not smooth pans, and none that could give you the illusion that you're not looking through a frame. Each pan sets into relief the rectangular delineation of the frame. It never moves obliquely, for example.

M: It's always horizontal. . . .

T: Or vertical.

M: And it's always referring back to you as an individual filmmaker behind the camera. It never becomes this sort of Hitchcock motion through space that makes the camera feel so powerful.

T: In someone else's space I cannot just roam about as I may like to. Roaming about with the camera is not value-free; on the contrary, it tells us much about the ideology of such a technique.

M: It's interesting too that the way you pan makes clear that the only thing that we're going to find out about you personally is that you're interested in this place. Much hand-held camerawork is implicitly autobiographical, emotionally self-expressive. In your films camera movement is not autobiographical except in the sense that it reveals you were in this place with these people for a period of time and were interested in them, rather than in what they mean to your culture.

T: There are many ways to treat the autobiographical. What is autobiographical can often be very political, but not everything is political in the autobiographical. One can do many things with elements of autobiography. However, I appreciate the distinction you make because in the realm of generalized media colonization, my films have too often been described as a “personal film,” as “personal documentary” or “subjective documentary.” Although I accept these terms, I think they really need to be problematized, redefined and expanded. Because personal in the context of my films does not mean an individual standpoint or the foregrounding of a self. I am not interested in using film to “express myself,” but rather to expose the social self (and selves) which necessarily mediates the making as well ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations, Filmography and Distribution.

- Film scripts

- Interviews

- Select Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Framer Framed by Trinh T. Minh-ha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Screenwriting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.