![]()

PART ONE

COMPLEXITY THINKING

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

WHAT IS “COMPLEXITY”?

EVERYTHING SHOULD BE AS SIMPLE AS POSSIBLE,

BUT NOT SIMPLER.

–Albert Einstein1

Early in the year 2000, prominent physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking commented, “I think the next century will be the century of complexity.”2 His remark was in specific reference to the emergent and transdisciplinary domain of complexity thinking, which, as a coherent realm of discussion, has only come together over the past 30 years or so.

Through much of this period, complexity has frequently been hailed as a “new science.” Although originating in physics, chemistry, cybernetics, information science, and systems theory, its interpretations and insights have increasingly been brought to bear in a broad range of social areas, including studies of family research, health, psychology, economics, business management, and politics. To a lesser—but accelerating—extent, complexity has been embraced by educationists whose interests extend across such levels of activity as neurological processes, subjective understanding, interpersonal dynamics, cultural evolution, and the unfolding of the more-than-human world.

This sort of diversity in interest has prompted the use of the adjective transdisciplinary rather than the more conventional words interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary to describe complexity studies. Transdisciplinarity is a term that is intended to flag a research attitude in which it is understood that the members of a research team arrive with different disciplinary backgrounds and often different research agendas, yet are sufficiently informed about one another’s perspectives and motivations to be able to work together as a collective. This attitude is certainly represented in the major complexity science think tanks, including most prominently the Santa Fe Institute that regularly welcomes Nobel laureates from many disciplines.3 By way of more specific and immediate example, as a collective, our (the authors’) respective categories of expertise are in mathematics, learning theory, and cognitive science (Davis) and literary engagement, teacher education, and interpretive inquiry (Sumara). This conceptual, methodological, and substantive diversity is not simply summed together in this text. Rather, as we attempt to develop in subsequent discussions of complex dynamics, the text is something more than a compilation of different areas of interest and expertise.

The transdisciplinary character of complexity thinking makes it difficult to provide any sort of hard-and-fast definition of the movement. Indeed, as we develop later on, many complexivists have argued that a definition is impossible. In this writing, we position complexity thinking somewhere between a belief in a fixed and fully knowable universe and a fear that meaning and reality are so dynamic that attempts to explicate are little more than self-delusions. In fact, complexity thinking commits to neither of these extremes, but listens to both. Complexity thinking recognizes that many phenomena are inherently stable, but also acknowledges that such stability is in some ways illusory, arising in the differences of evolutionary pace between human thought and the subjects/objects of human thought. By way of brief example, consider mathematics, which is often described in terms of certainty and permanence. Yet, when considered over the past 2500 years, mathematical knowledge has clearly evolved, and continues to do so. Even more contentious, it is often it is assumed that, while ideas may change, the universe does not. But, the viability of this sort of belief is put to question when ideas are recognized to be part of the cosmos. The universe changes when a thought changes.

The fact that complexity thinking pays attention to diverse sensibilities should not be taken to mean that the movement represents some sort of effort to embrace the “best” elements from, for example, classical science or recent postmodern critiques of scientism. Nor is it the case that complexity looks for a common ground among belief systems. Complexity thinking is not a hybrid. It is a new attitude toward studying particular sorts of phenomena that is able to acknowledge the insights of other traditions without trapping itself in absolutes or universals.

Further to this point, although it is tempting to describe complexity thinking as a unified realm of inquiry or approach to research, this sort of characterization is not entirely correct. In contrast to the analytic science of the Enlightenment, complexity thinking is not actually defined in terms of its modes of inquiry. There is no “complexity scientific method”; there are no “gold standards”4 for complexity research; indeed, specific studies of complex phenomena might embrace or reject established methods, depending of the particular object of inquiry.

It is this point that most commonly arises in popularized accounts of complexity research: The domain is more appropriately characterized in terms of its objects of study than anything else. In an early narrative of the emergence of the field, Waldrop5 introduces the diverse interests and the diffuse origins of complexity research through a list that includes such disparate events as the collapse of the Soviet Union, trends in a stock market, the rise of life on Earth, the evolution of the eye, and the emergence of mind. Other writers have argued that the umbrella of complexity reaches over any phenomenon that might be described in terms of a living system—including, in terms of immediate relevance to this discussion of educational research, bodily subsystems (like the brain or the immune system), consciousness, personal understanding, social institutions, subcultures, cultures, and a species.

Of course, the strategy of list-making is inherently problematic, as it does not enable discernments between complex and not-complex. To that end, and as is developed in much greater detail in the pages that follow (particularly, chaps. 5 and 6), researchers have identified several necessary qualities that must be manifest for a phenomenon to be classed as complex. The list currently includes:

• SELF-ORGANIZED—complex systems/unities spontaneously arise as the actions of autonomous agents come to be interlinked and co-dependent;

• BOTTOM-UP EMERGENT—complex unities manifest properties that exceed the summed traits and capacities of individual agents, but these transcendent qualities and abilities do not depend on central organizers or overarching governing structures;

• SHORT-RANGE RELATIONSHIPS—most of the information within a complex system is exchanged among close neighbors, meaning that the system’s coherence depends mostly on agents’ immediate interdependencies, not on centralized control or top-down administration;

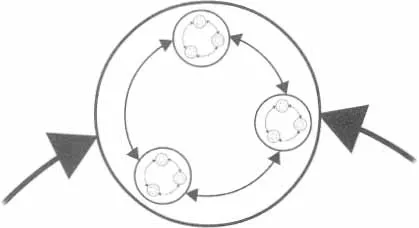

• NESTED STRUCTURE (or scale-free networks)—complex unities are often composed of and often comprise other unities that might be properly identified as complex—that is, as giving rise to new patterns of activities and new rules of behavior (see fig. 1.1);

• AMBIGUOUSLY BOUNDED—complex forms are open in the sense that they continuously exchange matter and energy with their surroundings (and so judgments about their edges may require certain arbitrary impositions and necessary ignorances);

• ORGANIZATIONALLY CLOSED—complex forms are closed in the sense that they are inherently stable—that is, their behavioral patterns or internal organizations endure, even while they exchange energy and matter with their dynamic contexts (so judgments about their edges are usually based on perceptible and sufficiently stable coherences);

• STRUCTURE DETERMINED—a complex unity can change its own structure as it adapts to maintain its viability within dynamic contexts; in other words, complex systems embody their histories—they learn—and are thus better described in terms of Darwinian evolution than Newtonian mechanics;

• FAR-FROM-EQUI1IBRIUM—complex systems do not operate in balance; indeed, a stable equilibrium implies death for a complex system.

FIGURE 1.1 FIGURATIVE REPRESENTATION OF THE NESTEDNESS OF COMPLEX UNITIES

We use this image to underscore that complex unities are composed not just of smaller components (circles), but also by the relationships among those components (arrows). These interactions can give rise to new structural and behavioral possibilities that are not represented in the subsystems on their own.

This particular list is hardly exhaustive. Nor is it sufficient to distinguish all possible cases of complexity. However, it suffices for our current purposes—specifically, to illustrate our core assertion that a great many phenomena that are currently of interest to educational research might be considered in terms of complex dynamics. Specific examples discussed in this text include individual sense-making, teacher—learner relationships, classroom dynamics, school organizations, community involvement in education, bodies of knowledge, and culture. Once again, this list does not come close to representing the range of phenomena that might be considered.

Clearly, such a sweep may seem so broad as to be almost useless. However, the purpose of naming such a range of phenomena is not to collapse the diversity into variations on a theme or to subject disparate phenomena to a standardized method of study. Exactly the contrary, our intention is to embrace the inherent complexities of diverse forms in an acknowledgment that they cannot be reduced to one another. In other words, these sorts of phenomena demand modes of inquiry that are specific to them.

Yet, at the same time, there are distinct advantages—pragmatic, political, and otherwise—to recognizing what these sorts of phenomena have in common, and one of our main purposes in writing this book is to foreground these advantages. But first, some important qualifications.

WHAT COMPLEXITY THINKING ISN’T

One of the most condemning accusations that can be made in the current academic context is that a given theory seems to be striving toward the status of a metadiscourse—that is, an explanatory system that somehow stands over or exceeds all others, a theory that claims to subsume prior or lesser perspectives, a discourse that somehow overcomes the blind spots of other discourses. The most frequent target of this sort of criticism is analytic science, but the criticism has been leveled against religions, mathematics, and other attitudes that have presented themselves as superior and totalizing.

Given our introductory comments, it may seem that this complexity science also aspires to a metadiscursive status—and, indeed, it is often presented in these terms by both friend and foe. As such, it behooves us to be clear about how we imagine the nature of the discourse.

To begin, we do not regard complexity thinking as an explanatory system. Complexity thinking does not provide all-encompassing explanations; rather, it is an umbrella notion that draws on and elaborates the irrepressible human tendency to notice similarities among seemingly disparate phenomena. How is an anthill like a human brain? How is a classroom like a stock market? How is a body of knowledge like a species? These are questions that invoke a poetic sensibility and that rely on analogy, metaphor, and other associative (that is, non-representational) functions of language.

In recognizing some deep similarities among the structures and dynamics of the sorts of phenomena just mentioned, complexity thinking has enabled some powerful developments in medicine, economics, computing science, physics, business, sociology … the list goes on. But its range of influence should not be interpreted as evidence of or aspiration toward the status of a metadiscourse. In fact, complexity thinking does not in any way attempt to encompass or supplant analytic science or any other discourse. Rather, in its transdisciplinarity, it explicitly aims to embrace, blend, and elaborate the insights of any and all relevant domains of human thought. Complexity thinking does not rise over, but arises among other discourses. Like most attitudes toward inquiry, complexity thinking is oriented by the realization that the act of comparing diverse and seemingly unconnected phenomena is both profoundly human and, at times, tremendously fecund.

An important caveat of this discussion is that complexity thinking is not a ready-made discourse that can be imported into and imposed onto education research and practice. That sort of move would represent a profound misunderstanding of the character of complexity studies. Rather, educational researchers interested in the discourse must simultaneously ask the complementary questions, “How might complexity thinking contribute to educati...