![]()

1

Between governmentality and global politics

Introduction

In recent years, the annual gatherings of Western political leaders, global corporate executives, and international financial institutions have not been complete without a crowd in the streets and a parallel conference down the road. Seattle, Geneva, Gothenburg, Genoa: these are all familiar city names, each conjuring up images of protestors and policy, of banners and broken windows, even of injury and death. Until the events of September 11, 2001, politics in the streets was coming to be seen as the greatest challenge to the forward march of global economic integration; some even warned that, if allowed to continue, opposition to the high politics of capitalism might cause the entire edifice to collapse (Notes from Nowhere 2003; Soros 2000). Since the attacks on New York and Washington, DC in September 2001, the so-called anti-globalization movement, renamed by its supporters the “global justice movement,” has been more subdued, perhaps fearful of being tagged as “terrorists” of one sort or another (e.g. Coulter 2003; Hannity 2004). Even so, the issues and problems that motivated the emergence of this movement—human rights violations, environmental destruction, unhealthy working conditions, child labor, violence against women, concern about genetically modified organisms, all of the appurtenances of what Ulrich Beck (1992) has called “the risk society”—have not disappeared. Economic recession and American wars notwithstanding, the workings of globalized capitalism continue to generate these offenses against people, against real live human beings.

On closer inspection, the protests that have attracted the lion’s share of media attention are only the visible tip of what might be characterized as a much larger social “iceberg,” a form of “transnational politics” based on activists stepping in where states and capital fear to tread. A growing number of nongovernmental organizations, social movements, lobbying groups, and even business associations and corporations—what I have called “global civil society” (Lipschutz 1992/93, 1996)—are “crossing” political, cultural, institutional, and territorial borders in an effort to globalize social activism. They are devising and implementing corporate codes of conduct, frameworks, and other rule-based arrangements designed to foster “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) and to fill the regulatory gaps left by governments unwilling or unable to engage in public policy and social regulation (Haufler 2001; Jenkins et al. 2002). In doing this, global civil society actors are not only intruding into what has long been considered the prerogative of sovereign states—international diplomacy and law—but are also transgressing into what has been considered the special preserves of scientists, lawyers, and technical experts—regulation and standard-setting (Braithwaite and Drahos 2000).

Thus, as we shall see in later chapters, the Forestry Stewardship Council has become a global leader in creating regulatory standards for sustainable forestry. UNITE, a garment workers trade union, has been targeting manufacturers whose clothing has been produced under sweatshop conditions. The International Organization for Standardization has formulated a set of environmental standards—ISO-14000—to which corporations can subscribe. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of other similar projects underway, all seeking to smooth down the rougher edges of what seems to be a largely self-regulating global capitalist system (Polanyi 2001; Hardt and Negri 2000). This book is about those issues and problems, the movements and campaigns to which they have given rise and the politics (or lack thereof) of such campaigns, and their intrusion into what have been seen traditionally as the zealously patrolled political spaces of states.

A second theme of this book addresses the tension between politics and markets that arises out of these regulatory campaigns and the corporate responses to them. The global justice movement is often depicted as a knee-jerk, misinformed and Luddite response to the inevitable and necessary economic and social changes of global scale and scope associated with capitalism (Thomas Friedman 1999; for convenience, I shall call these changes “globalization,” and define the term more carefully in Chapter 2). Such changes, it is frequently argued, are necessary if the world—and especially its impoverished regions—is to become more prosperous and its people happier and better off (Bhagwati 2002, 2004). Some disruption and reorganization of social relations are inevitable and necessary as part of this process. Moreover, resistance is both irresponsible and futile, for the alternative—which is never clearly specified—is too awful to contemplate (a common comparison is the sequence of the 1930s and World War II). The world’s poor require succor, and opposition by the global justice movement, as well as the unwarranted regulatory activities of activist campaigners, now stand as a “political” obstacle to improvements in the condition of the poor. Whether or not this view is correct, it is blind to the dynamics of both globalization and consequent social action as they play out on both the global and local stages. Moreover, the stylized setting up of this opposition between “markets” and “politics” obscures an interesting contradiction which convention tends to obscure. As we shall see, later in this chapter and this book, the tricks and tools relied on by both sides largely eschew politics in favor of market-based mechanisms in order to influence and manipulate producer behaviors and consumer preferences. What appears, at first glance, to be “political” is hardly that at all.

In using the term “politics” and “political,” I draw, in part, on Sheldon Wolin’s (1996) nomenclature.1 I do not refer here to the institutionalized procedures of liberal democracy, the rather undemocratic modes of decisionmaking found in international forums, or the behaviors of corporations in respect to their commodity production chains. I mean, rather, something more fundamental, involving the direct participation of people in those social choices having to do with the conditions and making of their own lives, individually and collectively (Arendt 1958; Mouffe 2000; see below and Chapter 8, where I distinguish between distributive and constitutive politics). To be sure, there is much in the way of procedural and managerial debate and contestation within and among countries as well as internationally among interested and concerned individuals and groups. But virtually all of these “politics” have come to be focused on the distributive consequences of contemporary global market conditions and forces under neoliberalism, that is, in Harold Laswell’s (1936) classical definition, as being “about who gets what, when, and how.” Most really existing political systems are not about politics in the democratic and expansive sense I propose in this book. Many do not even offer as much in the way of politics as Laswell’s phrase would suggest.

Indeed, even the contemporary democracies of the Anglo-American and European type are highly structured, stand-off representative arrangements, run mostly by unelected agencies, whose legitimacy is maintained through only a few basic modes of regulated participation. One involves the periodic casting of votes for one of a limited number of candidates or choices (better than pre—1989 socialism or Baathist practice, perhaps, but still quite constrained). Another joins together like-minded individuals who seek fulfillment of their self-interests through various forms of lobbying and public education (forms of collective behavior sometimes viewed as a “threat” to representative democracy; see Huntington 1981). The demos, as it were, has scant chance to engage in any kind of direct participation in or, for that matter, deliberation about representative arrangements, about the issues debated in legislatures, or about the outcomes that result from the actions of their representatives. These were all decided long ago and are not to be revisited. Moreover, if some part of the demos should seek to gain political voice through direct action or participation, as seems to be the case with the global justice movement, it is regarded as a rabble, a mob, and a threat to social stability (e.g. Latour 1999: ch. 7).

The very legitimacy of a democratic system depends, nonetheless, on the widely held conviction that its arrangements are representative, that representation takes place through essentially fair and equitable mechanisms open to broad participation, and that those elected do a fair and impartial job of representing those who did cast their vote, those who voted for other candidates, and those who could not be bothered to go to the polls (Habermas 1975). The claim that each of these principles is fulfilled by really existing democracies is questionable and rightfully under challenge by the global justice movement and others (left, right, center, and out in front). If “politics” is present within democratic states only in a pale, washedout form, how much less is it in evidence among states, in international forums and activities, where representative links are highly attenuated and capital has been gaining an ever-stronger hand? It is this lack of legitimacy, and the absence of the political, that are being protested by the global justice movement and addressed by campaigns for global social policy and regulation.

A third focus of this book thus concerns the perennial question: “What are we to do?” Most analyses of global problematics offer important critical insights into causes and consequences, as well as policies for addressing them, but they rarely take on the normative task of devising a political project. In the final chapter of this book, I attempt to frame such a project. I argue that, before we can “do” anything, we need first to recognize what has gone missing as a result of globalization and map out a restoration of the political, in a thick, participatory sense. How might we restore the political, a small-d democratic politics, not only to global movements but to everyday life? How might we generate a practical process that restores the political not only to the formulation of social policy but also to other activities, especially when governments seem reluctant, and indeed fearful, of doing so? How can we embark on what David Harvey (2000: ch. 9) has called a “dialectical utopia” rather than continue to imagine or fantasize about ideal worlds that, in the face of contemporary reality, appear unachievable?

The dictum that “all politics is local,” attributed to the late Massachusetts Congressman Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, seems especially apposite here. Under conditions of globalization, as we shall see, it might be extended to read “and all local politics is global, too.” By this, I mean to emphasize that the distributive politics of the global political economy has reached into almost all corners of everyday life, exercising a governmental power in which the average person has little voice or freedom. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s work on governmentality (1980), I suggest that what is necessary is not the global wielding of the power to influence, to paraphrase Robert Dahl (1957), but, rather, to produce power “locally.” To make this possible, a restoration of the political to everyday life, and the “acting” on which it depends (Arendt 1958), is essential. I do not refer here to the politics of liberal democracy and its “town hall” meetings. Nor do I mean the Habermasian politics of discursive democracy (Habermas 1984), which is necessary to but not sufficient for such a project. I do mean something more than the politics of global civil society which (Lipschutz 1992/93), as we shall see, feeds more into modest reforms in the institutional manifestations of globalization than the restructuring that is necessary to a truly political project.

To summarize, this book, then, is about the possibilities of meaningful and effective politics under the conditions of globalized capitalism and the hegemonic discourse of markets offered as the answer to all problematics, large and small. I examine a set of collective responses to these problematics, manifested in the transnational regulatory projects undertaken by activists, corporations, and consumers. I offer a critique of the dominant approach found in these regulatory projects—what I call “politics via markets”—and show why such efforts to regulate the social impacts of globalized capitalism cannot ameliorate, much less eliminate, them. Finally, I examine the possibilities of a global politics whose practitioners are schooled in local politics based on the political, philosophical, and practical cross-fertilization among locally situated but socially diverse epistemes.

An “episteme,” as I use the term in this book, is something akin to the “networks of knowledge and practice” about which I have written in earlier works (e.g. Lipschutz with Mayer 1996; see also Ruggie 1975, who draws on Foucault).2 Here, it refers to groups of people who are active in “face-to-face” settings that constitute political community (Arendt 1958) but informed and motivated by what might be understood as a common set of normative views, principles, and goals. Most of the epistemes with which we are familiar—even those that may seem radical by conventional standards, such as some variants of environmentalism (Lipschutz 2003: ch. 2)—are Western, liberal, and economistic. There are nevertheless any number that do not fall into these categories yet are activist, democratic, and materialistic, oriented toward nomos3 rather than demos. Such epistemes have a great deal to offer to contemporary politics and political possibilities, but must be listened to on their own terms. I do not write here of a merging of epistemes, or the colonization of one by another. Rather, I refer to a process of cross-fertilization between different approaches to and views of politics, resulting in a praxis that does not collapse back into the state—although I do not, here, dispense with the state as many might wish to do. I believe that the state will not and must not disappear, although it must be reconstituted and reconstructed. To engage in a truly democratic and active politics, I argue, we must develop a politics that is sensitive to local settings, that is respectful of local agents, and that is aware of the place of the global in the local.

The new global political economy of regulation

This book began its life as a study of civil society projects intended to develop and deploy social and environmental regulations in what are largely un- or underregulated international settings (Chapter 2). Such projects are the focus of Chapters 4 through 6. They are the work of private and semi-governmental groups and organizations based in global civil society (discussed in Chapter 3) and include:

• activist campaigns to embarrass and cajole corporate producers into self-regulation via codes of conduct;

• organizations whose goal is the promulgation of processing and production standards for goods and commodities;

• movements to sanction international trade in certain goods and commodities in order to constrain violence and human rights abuses in particular countries; and

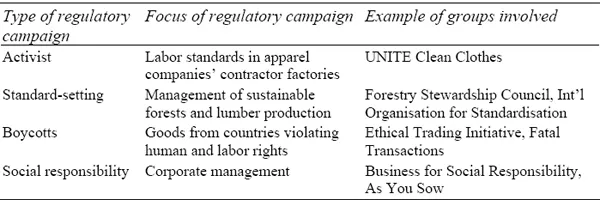

• corporations, corporate associations, and programs seeking to institute “corporate social responsibility” in production and sales of various types of goods and commodities (examples of such projects can be found in Table 1.1).

Why are such regulatory activities deemed necessary, and why are they taking place now? Why are these campaigns so focused on modifying the behavior of producers and consumers? Why don’t those who are concerned about social and environmental conditions focus on changing political regulation in those countries where these problems have emerged?

Some degree of regulation is generally demanded by producers and capitalists, who believe that a “level playing field” and a high degree of legal certainty are essential for economic success. For smaller businesses, regulation may also provide some protection against predatory and monopolistic behavior by larger ones. But “too much” regulation is strongly resisted in the view that it imposes excessive and unfair costs on capital. Consumers tend to demand regulation because they believe it protects them from unscrupulous and rapacious producers and provides safeguards against dangerous activities and products. (Whether regulation actually does such things is not, at this point, of concern, although I do address this question later in this book.) Finally, governments demand regulation—notwith-standing neo-liberal and libertarian rhetoric—in the hope that other governments and actors will act in a predictable, rule-based manner (this hope is at the core of regime theory; Krasner 1982).

Table 1.1 Examples of private international regulation

It is useful, in this context, to distinguish between “constitutive” rules and regulations, which organize and structure markets, and “distributive” (or instrumental) rules and regulations, which govern behavior between parties within markets (Lipschutz with Mayer 1996:36). Conventionally—or, at least, according to standard theories—regulation develops for two reasons.4 First, markets do not emerge “naturally” out of some human propensity to barter and exchange. They are social institutions, based on constitutive “rules of the game,” which develop over time or are created by authoritative bodies. Such rules legitimize markets’ existence and instill normative discipline in those who engage in exchange within them according to distributive rules. Many of the constitutive or structural rules are rarely questioned or examined, but some, such as property rights, are legislated or reified as “natural law.” Such rules do establish the certainty demanded in situations of decentralized exchange, such as markets, but they can also limit the potential for change and flexibility.

Second, many economic activities impose social costs on the general public that accrue to its detriment or generate unjustified benefits to certain private parties. This tendency is sometimes described as “privatization of benefits, socialization of costs.” As explained in Chapter 2, I have borrowed the term “externality” from neo-classical economics to describe such benefits and costs, although other terms and discourses, such as “risk” or even “human rights violations,” have also been applied to the phenomenon of unpaid social costs.5 The creation and existence of externalities are often couched in terms of “market failure,” that is, the failure of markets to include the costs of things that cannot be commodified or valued. Market failure can be remedied, according to the conventional wisdom, by including social costs in the price of a good, but this is not as easy as it sounds.

It is not always evident, moreover, that markets have “failed.” It may be, instead, that they have been organized with the intention of socializing certain costs and realizing private benefits, as is the case when, for example, pension rights are eliminated in the name of “efficiency.” Indeed, under capitalism the very organization of states and markets, as we...