1.1.a Singularity University, Silicon Valley, USA

The Singularity University (SU) starts not from a model of the typical all-purpose university but from a specific, focused, and unifying theme, as expressed in the strap line on their homepage: to “assemble, educate and inspire a new generation of leaders who strive to understand and utilize exponentially advancing technologies to address humanity’s grand challenges” (http://singularityu.org/). Such a thematic view cuts across separate subject areas. It is a direct response to the contemporary moment, in which the rate and the hybrid nature of technological change creates a demand for education across many academic and applied disciplines. As cofounder Peter Diamandis says, he “realised there was no place I could go and learn this stuff without getting a PhD in multiple fields. I said to myself, I bet there’s a great market for an international interdisciplinary university teaching all the exponential technologies” (Rowan 2013).

Cofounded with Ray Kurtzweil in 2008—and linked to his work in The Singularity is Near (2006)—the university is based at NASA’s Ames site. It began as a summer school and is now expanding into a much larger operation, with an intended global reach. Its business model comes from the conventional logic of achieving a high ranking, status, and reputation. Its market is an elite audience, paying large fees for a variety of events and courses, and benefiting from working with world-famous guest speakers, specialist faculty, and having access to high-quality equipment and resources:

The four- and seven-day executive programmes—six this year—help to fund the ten-week graduate-studies programme, in which 80 carefully chosen international students split their time between lessons and “creating projects that will impact humanity”. After about 160 lectures and several days of intensive workshops, they work on business ideas that could potentially affect a billion people. Last year there were 4,000 applicants from 120 countries for the 80 slots. […]

The project is also scaling up. The university recently acquired the Singularity Summit conferences and the Singularity Hub web portal; and it will launch two-day Singularity Summits in various cities. Online education will be “a huge initiative for 2013”, according to Gabriel Baldinucci, in charge of development and strategy. “It will be a paid course. We see ourselves as very complementary to graduate schools.”

(Rowan 2013)

The university has also moved from nonprofit to a for-profit benefit corporation, because a central aim is to create business incubators and take stakes in spun-out companies. Crucially, SU is not accredited and does not plan to become so: “You need to fix your curriculum for that,” says Salim Ismail. “We change ours five times a year! One of the deans at Stanford proudly told me they update theirs every six years. But if you’re doing a master’s degree today in neuroscience or advanced robotics or biotech, by the time you finish you’re out of date” (quoted in ibid.).

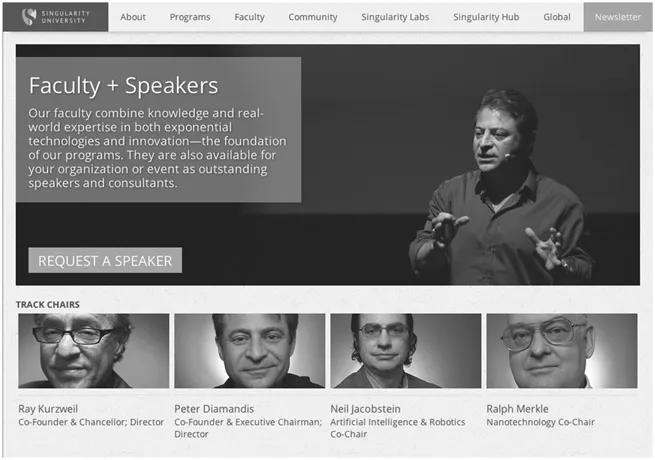

So, here is a university that does not give awards but still promotes itself as a high-quality and innovative educational institution, albeit via the conventional norms of the sector: based on the reputation of its academics and on the excellence of the provision. It is also likely to be successful in competing for, and attracting, high-achieving students who, in turn, will cement its reputation. For Diamandis, “we’re building a university here, a community, a family of people who are thinking about the future. And we’re iterating. This is just the beginning. In a world where the biggest problems on the planet are the biggest market opportunities, why wouldn’t you be focusing on them?” (ibid.). SU, then, competes with the most elite universities worldwide, with a unique selling point (USP) that challenges a reliance on history and tradition to guarantee quality. But unlike the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab, say, that also combines courses with start-up opportunities, SU can be very flexible and adaptable, offering a variety of courses at market prices with fewer overheads or external oversight demands. It cross-subsidizes single semester courses with commercially priced one-off events (in the summer of 2013 $12,000/£7,650 for a seven-day program) and aims to ‘sweat’ all its assets, including offering its faculty up as guest speakers (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Singularity University’s ‘request a speaker’ webpage

The underlying tendency—toward an emphasis on current technologies and interdisciplinary development—is, of course, being reflected elsewhere, often linked as with SU to direct entry into the elite global educational market. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology opened in 2010 and is already the world’s sixth-richest university, with a $10 billion endowment. Like SU, it does away with academic departments, instead having four interdisciplinary research institutes focusing on biosciences, materials science, energy and the environment, and computer science and math.

1.1.b The New College of the Humanities, London, UK

The philosopher A. C. Grayling’s new London-based educational institution, the New College of the Humanities (NCH), also aims for an elite clientele, but this time not so much looking ‘forward’ as ‘backward’ based on precisely the idea of tradition and heritage as a marker of quality. It offers a traditional liberal arts education, reclaimed from what Grayling considers the latest fads and unnecessary bureaucratic requirements of existing universities, to focus on the “study of the humanities [which] provides personal enrichment, intellectual training, breadth of vision, and the well-informed, sharply questioning cast of mind needed for success in life in our complex and rapidly changing world” (NCH 2013: 4). It is framed around the Oxbridge model of small-group teaching, very regular writing tasks and individual tutorials with faculty. Begun in 2012, NCH is still a tiny organization, but has received a lot of media attentio...