eBook - ePub

Images of Lust

Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches

James Jerman, Anthony Weir

This is a test

Share book

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Images of Lust

Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches

James Jerman, Anthony Weir

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sexually explicit sculptures may be found on a number of medieval churches in France and Spain. This fascinating study examines the origins and purposes of these sculptures, viewing them not as magical fertility symbols, nor even as idols of ancient pre-Christian religions, but as serious works that dealt with the sexual customs and salvation of medieval folk, and thus gave support to the Church's moral teachings.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Images of Lust an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Images of Lust by James Jerman, Anthony Weir in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Storia dell'arte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Sheela-na-gig

. . . one of those old Fetish figures called ‘Hags of the Castle’ . . .

Windele

. . . or Julia the Giddy, or the Girl of the Paps, or the Whore, or the Idol, or St Shanahan, or Cathleen Owen, or Sheila O'Dwyer . . .

Many names have been given at various times and in different places to the indecent carvings which first came into prominent public discussion among antiquaries in nineteenth-century Ireland. The attempts of philologists and historians to trace the etymology of sheela-na-gig in its many Irish and English spellings are admirably reviewed in the first long book to be written on the subject of these carvings: the doctoral thesis for the University of Copenhagen of Jørgen Andersen, published in 1977 under the title ‘The Witch on the Wall: medieval erotic sculptures of the British Isles’ (Andersen 1977). It gave a catalogue of the then known figures together with a number of chapters of commentary and discussion. Readers curious to know about forms like ‘sile na gCíoch’ could not do better than to turn to Andersen's second chapter. Here we can only say that a great deal of obscurity surrounds the term and its inception. But since sheela-na-gig, the anglicised form of a dubious Irish expression, has gained so wide a currency to indicate the carving which the Shell Guide to Ireland (Killanin & Duigan 1967) calls ‘an obscene female figure of uncertain significance’, we shall continue to use the term (or its shortened form sheela) when we speak of female sculptures. Because our study also takes into account male sexual sculptures, which in France and Spain are more numerous than female, we shall use a more general term when referring to figures of both sexes, namely, ‘sexual exhibitionists’ or simply ‘exhibitionists’.

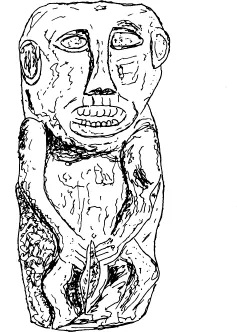

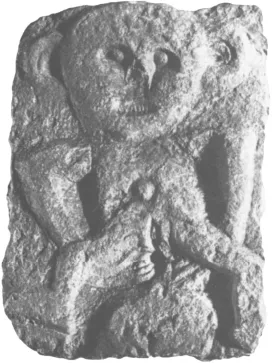

At the outset we would do well to clarify two terms which have often been used in connection with such carvings. The first is the word ‘erotic’. In its purest sense, this word denotes something capable of arousing love or exciting sexual feeling. When applied to a work of art, we expect to sense a sexually-arousing reaction to the piece of work. We cannot think the term is applicable to the exhibitionists we are going to consider. Admittedly these sculptures are sexual and draw attention to the genitalia by a flagrant display often highlighted by the play of the hands; but an equally distinctive feature of the sheela is its repellent ugliness: huge disproportionate head, staring eyes, gaping mouth, wedge nose, big ears, bald pate, herculean shoulders and twisted posture (Fig. 4) As Andersen repeatedly states, the sheela is a frightening hag whose message does not seem to be immoral but is rather aimed at dispelling any sexual predisposition the viewer might entertain. We suggest in this book that the function of sexual exhibitionists is not erotic but rather the reverse, that these extraordinarily frank carvings were more probably an element in the medieval Church's campaign against immorality, and that they were not intended to inflame the passions but rather to allay them (Plates 4, 5 and 6).

Secondly, we pass under review another popular term, used by us as well as others, when describing such sexual carvings – the word ‘obscene’. In the course of this essay it will become apparent that medieval masons did not consider these images to be obscene. Crude, vulgar, not without satirical or sardonic humour, they were executed in the full knowledge that they might shock or give offence. Indeed, that was most probably the intention. But they were not pornographic, or sacrilegious; nor were they inconsequential. In spite of their grossness, their comic exaggeration and impossible postures, they were, in their own small way, serious works. That is not to say that there are never any instances of trivial carvings, the expressions of a mason's virtuosity or humour, but we hope to show that the great majority once formed part of a planned artistic composition, whose several parts combine to create a cumulative effect of high seriousness.

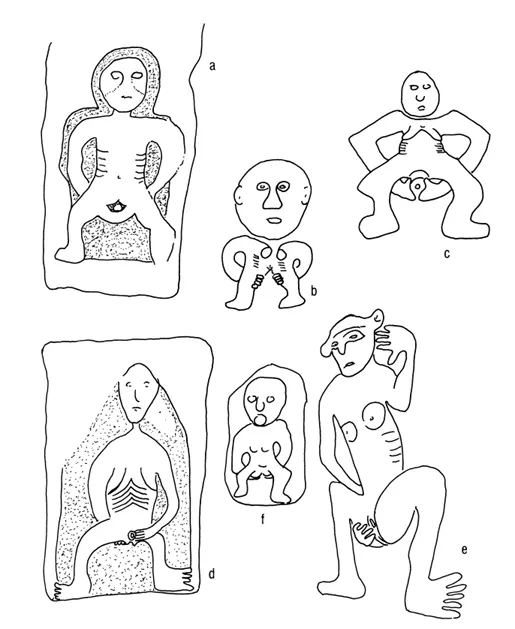

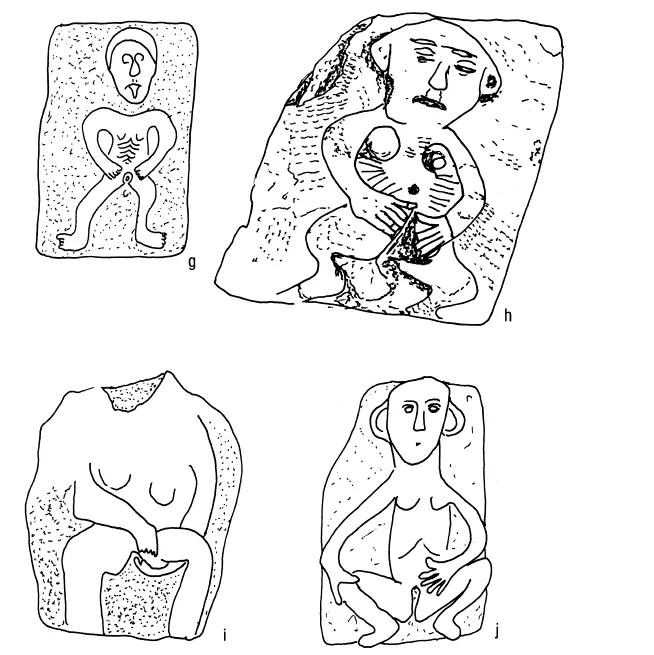

Fig. 2a Insular sheela-na-gigs illustrating the role played by the hands. Type I shows both hands behind the buttocks; Type II only one hand behind; Type III both hands in front; Type IV one hand in front (for a fuller explanation see Jerman, Dundalk 1981). (a) Blackhall Castle, Type I; (b) Doon Castle, Type I; (c) Ballyfinboy, Type I; (d) Clomantagh, Type II; (e) Tullavin Castle, Type II; (f) Lixnaw, Type I.

Over the centuries much medieval carving has been thought so crude as to merit destruction, and, where this has happened, leaving behind in isolation the exhibitionist figures, it is understandable that one should be taken aback by the vulgarity of the decontextualised vestiges. If what survives seems to us obscene, the fault is partly within ourselves, since we have become conditioned by our education and upbringing to misrepresent to ourselves the moral climate that prevailed during the early Middle Ages. (The whole question of ‘obscenity’ in art has been admirably examined by Catherine Johns in her study of the ‘erotica’ in the British Museum (Johns 1982).)

Fig. 2b (g) Cloghan Castle, Type III; (h) Llandrindod, Type III; (i) Killaloe, Type IV; (j) Ballylarkin, Type IV.

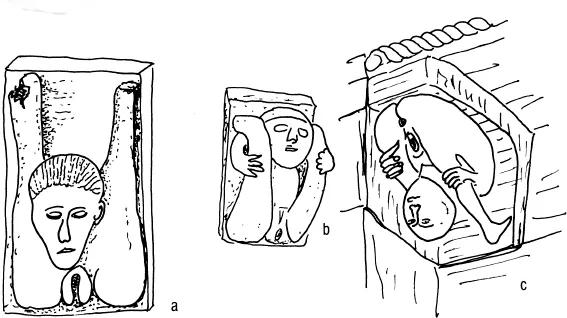

Fig. 3 Some Continental female exhibitionists in the feet-to-ears position: (a) Assouste; (b) Corullón (also displaying anus); (c) Mauriac (upside-down acrobat, also displaying anus).

Fig. 4 ‘Chloran’ from Killua, Westmeath, in the British Museum (Witt Collection), shows typical ugliness.

There is no need to give a history of the discovery of sheela-na-gigs by nineteenth-century antiquarians, since Andersen has done this most admirably (Andersen 1977). He supplies a very full bibliography, covering not only all the discussions of the 1840s, but also the very many articles which have appeared, especially since attention was drawn to the notice of a wider public by the first anonymous list in 1894, and the much fuller list and taxonomy by Dr Edith M. Guest in 1935 (Guest 1935). We need only add a little further historical note of evidence that has recently been brought to our attention (Ross 1983). One of the volumes of the Helicon History of Ireland, The Catholic Community in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries 1981, contains a number of references to sheelas earlier than any so far known. These references occur in diocesan and provincial statutes of the seventeenth century:

1 In 1631, provincial statutes for Tuam order parish priests to hide away, and to note where they are hidden away, what are described in the veiled obscurity of Latin as imagines obesae et aspectui ingratae, in the vernacular ‘sheela-na-gigs’, i.e. at that time priests had begun to take notice of these ‘fat figures of unpleasant features’ and to remove them.

2 ... a Diocesan (Ossory) regulation of 1676 ordering ‘sheela-na-gigs’ to be burned. Bishop Brehan in Waterford was ordering exactly the same thing that year . . .

3 . . . the Kilmore diocesan synod excluded from all sacraments . . . those whom the synod calls gierador – they might perhaps be described as ‘living sheela-na-gigs’.

This last reference gives support to the evidence that in some country districts ‘sheela-na-gig’ was a term used to indicate women of loose morals or simply old hags. These regulations also contain further evidence that many sheelas were destroyed or buried, and that once upon a time there must have been a great many more than we can see today.

Another comment may be made at the outset. If Spanish and French antiquaries and writers of the history of art had shown the same curiosity and interest as their Irish counterparts in studying and cataloguing the hundreds of exhibitionist carvings around them (and to this day they still have not done so), then it is our view that a number of misconceptions might never have arisen:

1 sheelas would not have been regarded as purely insular phenomena;

2 their origin would not have been attributed to pre-Christian fertility or other cults;

3 their function would not have been described as mainly a tutelary, apotropaic one;

4 their dating would have been established in all probability as no earlier than the eleventh century,

5 and their study would not have been relegated to obscure journals but undertaken openly, like that of other sculptures of their period.

As it is, we have had to wait over a century and a half for work like Andersen's. Our own belated contribution aims to show that sexual exhibitionists developed, like so many other Romanesque motifs, from Classical prototypes at a date not earlier, so far as we have been able to ascertain, than the eleventh century, and that their floruit was during the twelfth century; that they are Christian carvings, part of an iconography aimed at castigating the sins of the flesh, and that in this they were only one element in the attack on lust, luxury and fornication; that their horrible appearance is due to the fact that they portrayed evil in the battle against evil; that, in this role of warring against Luxuria and Concupiscentia, two of the Mortal Sins, they flourished in the sculpture of a well-defined area of western France and northern Spain; that they reached the British Isles by a process we shall describe; that they were supported by a number of carvings which at first sight seem to be unconnected with them, and which are better understood when the connection has been made, and that it is possible that the apotropaic purpose sometimes attributed to them is a later development, stemming from the forcefulness of their imagery and the respect with which they were regarded. In all this, the solutions we offer to problems posed by the sheelas and other sexual figures will be simple ones, of the kind that ought to have been expounded long ago. These solutions, which are free of mystification, and are supported by our illustrative material, ought to be more plausible than much of what has been written on the subject.

Plate 4 Sheela from Cavan, similar to ‘Chloran’ (Fig. 4). (Photo: Nat. Museum of Ireland, Dublin)

Plate 5 Sheela at Kilpeck, Type I. The fact that it is not entirely human is significant. Either the sculptor was embarrassed (not likely) or he meant to portray the act as beastly. (Photo: J. & C. Bord)

We have been blinkered in the past by our restricted horizons in the study of the insular carvings. The solution to the problem of what these figures are and why they occur on churches is not to be found at home but on the Continent. Andersen (Andersen 1977) does tentatively suggest the European connection but, since his study was intended to examine only the insular pieces, he did not pursue it; he did, however, mention some 11 in France (none in Spain), 40 or so in England and over 70 in Ireland. A few have come to light since his work was published – we list them in Chapter 10. He states:

There seems to be no great mystery about the origin of the motif in the British Isles; it could well have arrived with other motifs to enrich the repertoire of carvers looking generally towards France and the Continent for inspiration.

And, in describing the corbel table of Saint-Quantin-de-Rançannes, he adds:

It is a context in which we approach the Irish sheelas closely, if we have not in fact found a model for them.

Plate 6 Sheela from Ballyportry Castle. (Photo: Nat. Museum of Ireland, Dublin)

Furthermore, he tells us that he was informed by the Secretary of the Commission d'Inventaire for the Poitou-Charente district that there are over 100 exhibitionists in that part of France alone. Our own by no means exhaustive searches have identified over 70 female exhibitionists in France, some 40 in Spain, an even higher number of male exhibitionists in both countries (we gave up trying to count them), and many other figures allied to them by their sexual display or attributes (e.g. coital couples, simple frontal nudes, anus-showers, acrobatic penis-swallowers, testicle-showers, megaphallic men, and so on). Figures such as grimacers, tongue-protruders, beard-pullers, tress-pullers and mouth-pullers often display their sex organs as well and are therefore exhibitionists (especially when megaphallic). Even if these latter figures are not displaying their genitalia, the fact that they ...