![]()

1

Gangs and the Community

History from below

I shall begin with this proposition – one that is so commonplace that its significance is often overlooked – that in our society, youth is present only when its presence is a problem, or is regarded as a problem. More precisely, the category “youth” gets mobilized in official documentary discourse, in concerned or outraged editorials and features, or in the supposedly disinterested tracts emanating from the social sciences at those times when young people make their presence felt by going “out of bounds,” by resisting through rituals, dressing strangely, striking bizarre attitudes, breaking rules, windows, heads, issuing rhetorical challenges to the law.

(Hebdige 1988:18)

Approaching the subject of gangs outside of any historical context is impossible, yet this “oversight” is precisely what characterizes most gang studies today, particularly those that come increasingly from the field of criminal justice. As Hebdige makes abundantly clear (see above) when he locates youth as a subject/object of investigation, derision and fear in history, it is only when youth are associated with “trouble” that they become worthy of society’s doubtful attention – and there is no greater shorthand for this pejorative association between youth and trouble than “the gang.”

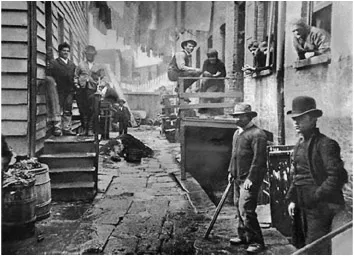

FIGURE 1.1 Bandit roost (59 Mulberry Street in New York City), photo taken by Jacob Riis in 1888.

In this chapter I want to discuss the various aspects of the relationship between the gang and history, drawing on my own research as well as that of numerous colleagues in the gang field and on a corpus of iconoclastic work often referred to as “history from below”1 and its corollary in historical ethnography (see in particular the work of Comaroff and Comaroff 1992). In so doing I want to argue that renditions of the gang without history place the phenomenon at the mercy of empiricist accounts that pay scant attention to the politics of representation in an era of extreme privilege on the one hand, and privation, punishment and cruelty on the other (Giroux 2012). We need to take seriously the literature that has resisted the temptation to reproduce elite readings of deviance and deviants and instead has sought to place such claims in a historically grounded framework of indirect violence (Salmi 1993), competition over material resources and symbolic (mis)representations. Second, I argue that disregarding history’s importance in the making of gangs leads to a failure to understand the multiple contours of development through which a community must emerge, particularly along the fault lines of race and class and the political economy of space. Finally, I argue that, without the historical lens, we will reproduce representations of the gang that serve the hegemony rather than a critical reading or deconstruction of the phenomenon that allows us to see how that hegemony is achieved in the first place. As Howard Zinn (2005 [1980]:11), one of the pioneers of the “people’s history” approach, wrote in the introduction to his acclaimed work:

this book will be skeptical of governments and their attempts, through politics and culture, to ensnare ordinary people in a giant web of nationhood pretending to a common interest. I will not try to overlook the cruelties that victims inflict on one another as they are jammed together in the boxcars of the system. I don’t want to romanticize them. But I do remember (in rough paraphrase) a statement I once read: “The cry of the poor is not always just, but if you don’t listen to it, you will never know what justice is…” If history is to be creative, to anticipate a possible future without denying the past, it should, I believe, emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even if in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together, occasionally to win. I am supposing or perhaps only hoping, that our future may be found in the past’s fugitive moments of compassion rather than its solid centuries of warfare.2

Not too many “saints” in the East End

I suppose coming from a highly marginalized and stereotyped community of East London (Jack London (2011 [1903]) called us the “People of the Abyss” early last century), I am loathe to accept deviance at its face value, particularly when it is said to be a societal threat. Through my own personal history of membership in both “skinhead” street corner groups and the early legions of soccer “hooligans” during the late 1960s it became clear to me that society would always cast the antics of middle-class progeny in sharply different colors and tones than those of the working-class. The “saints” would never be the ones hanging out on my block but the “roughnecks” could be seen in their small gatherings about every 100 yards. As I later learned, the presence of these “street corner societies” had little to do with the roughnecks’ intrinsic properties but everything to do with those who made claims about us, telling the world who and how we were and what we stood for.

At the moment in the United States, despite massive collective and conspiratorial abuses of the financial system by banks, mortgage lenders, insurance companies, accountancy firms, ratings agencies and brokerage houses exposed by the meltdown of 2008 (Will et al. 2013), hardly an upper-class culprit spent a single day behind bars. Bernie Madoff was the exception, not the rule, as his ownership of the massive pyramid scheme became too big to ignore and leave unpunished in the eyes of the public. Yet his lifestyle of rampant illegal drug use, corruption and debauchery, and his working assumptions about the diverse scams of casino capitalism, went unchecked for years because such behavior was normative and shared by many of his fellow players, who happen to shape the rules by which the game is played. Do these bankers and financial titans behave like a gang, meeting secretly over time, having their own clubrooms, organizing and protecting their own territory, carrying out predatory actions against adversaries, showing loyalty to the group and so forth? Many would say they do and that they perpetrate and encourage extraordinary levels of social harm on innocent bystanders far in excess of the injuries caused by so-called “gangs.”

Nonetheless, despite the obvious criminal deviance of the elites we are advised by the FBI that it is the Mara Salvatrucha street gang that is the number one organized crime group in the United States. Strange as it might seem for a street subculture to be accorded such an elevated status, when one thinks of the decades-long investigation and prosecution of the various US mafias by law enforcement agencies or the prolific organized rule-breaking of industrial and financial leaders as mentioned above, nonetheless such obviously dubious claims, made by one of the country’s leading policing agencies, are rarely questioned or considered “an issue.” The obvious politics behind the representation and misrepresentation are hardly ever contested.

And so it goes with most studies of gangs, whose premises are simply taken as given, with gangs usually defined and discovered by legitimated social control agencies and their broad ranks of affiliated “experts,” most often drawn from the police, the criminal justice system or the correctional industry. Thus it is rare for researchers, sociologists or other social scientists to step back and reflect on the processes of epistemology (e.g. categorization and social recognition) and place such “knowledge,” often coming from above, in some historical context such that it can be interrogated by a knowledge and history from below. As social scientists we should not only be asking ourselves whether our theories, categories and definitions are empirically proven but why are these the only data worthy of consideration? Why, for example, is there such a vast criminology of the gang and no criminology of genocide or war (Morrison 2006)? What properties of the group and its members are included or excluded in the analysis? How or why do certain groups get named in the first place? Who or what benefits by this process of naming, discovery and measurement? Such questions, of course, are par for the course in more critical investigative approaches or discourses such as social constructionism and labeling theory in sociology or in cultural criminology, and I shall return to some of these debates later in the book. For now I am simply raising these issues to urge us to think more critically and reflexively about the gang in history, i.e. as a social phenomenon that is said to emerge within the ebbs and flows of social, economic and political currents over time; or as a group or subculture that possesses a set of meanings that are contested and contestable in a world that, as Galeano warns, is increasingly “upside down” and dystopic.

Thus, to think about the gang in history requires us to consciously place the phenomenon we are describing in a set of intersecting, overlapping, unequal power relations where depictions and constructions of the unrighteous are frequently without merit and allowed to go unchecked, especially in the current dominant discourse of crime control, risk management and border protection. As a result the practices of a more or less rational counter-discourse have been growing, even though they might be sometimes difficult to observe when set against the tsunami of orthodox criminological and criminal justice renderings of the gang Other.

The gang in history and the gang with history

In Pearson’s (1987) work on the historical emergence of the “hooligan” we see an excellent example of an historical materialist or realist approach to the construction of a deviant group, in this case the notion of the hooligan. Played out within the processes of a “moral panic,” or what Pearson calls “respectable fears,” Pearson interrogates the presence of the new, dangerous youth “underclass” in Britain (during the 1980s) by carefully going back into the past to uncover periods and instances when a rapidly urbanizing and industrializing England was similarly finding other dangerous “underclasses” as it struggled to cope with the lower orders increasingly transgressing their social boundaries and infiltrating the spaces of the middle and, to a lesser extent, upper classes. The results of his inquiry are prosaically told and serve to describe in some detail how ready members and representatives of the Establishment, often via their media mouthpieces, were to denigrate and condemn the behavior, modes of dress, and organizational capabilities of lower-class youth for their perceived threats to such middle-class strictures as “fair play,” self-control and the “stiff upper lip.”

Thus, the unruly behavior of soccer fans at games, increasingly popular as a mass spectacle at the turn of the century, the drunken comportment of working-class patrons in depraved public spaces such as “pubs,” or the bawdy “music hall” influence on lower-class culture, and last but not least the sight of lower-class men and women improving their lot through pedal power, were all the topic of frequent denunciations. As Pearson (1987:66) puts it:

undoubtedly the most extraordinary aspect of this grumbling against the tendency of the working-class to assert its noisome presence in places it clearly had no right to go, was to be found in the “bicycle craze” of the 1890s.

Pearson goes on to analyze the moral opprobrium against the feckless behavior of working-class youth in the 1920s and 1930s whilst studiously overlooking the deepening conditions of poverty and extreme exploitation during the Depression. In so doing he argues that there is a prevalence of nostalgia for an idealized, often racially pure, past, citing the example of Richard Hoggart (1957) in the 1950s, whose pioneering work on working-class culture also held to a pastoral version of the lower classes as he lamented the influence on youth of “Americanized” mass entertainment via television, film and rock and roll. Although there were, of course, oppositional narratives to these moralizing discourses from more radical and socialist commentators, Pearson reveals a general absence of self-articulated versions of daily life by the perpetrators of these transgressive behaviors, or what we now call a history from below.

Thus Pearson emphasizes that it is incumbent on social scientists to fully engage claims made about the agents of order and disorder by comparing such claims to other, past instances when social outrage was also an issue and thereby to place the present in a more revealing comparative past. Such a context is necessary to demonstrate more fully what the continuity and discontinuities are in terms of the power to represent and to concoct symbols that have lasting influence on both the private and public imaginations. As Pearson (1987:236) reminds us:

The way to challenge the foundation of myth, to repeat, is not to deny the facts of violence and disorder. Rather, it is to insist that more facts are placed within the field of vision … When the cobwebs of historical myth are cleared away, then we can begin to see that the real and enduring problem that faces us is not moral decay, or declining parental responsibility, or undutiful working mothers, or the unparalleled debasement of popular amusements – or any other symptom of spiritual degeneration among the British people. Rather, it is a material problem. The inescapable reality of the social reproduction of an underclass of the most poor and dispossessed.

If we substitute “the hooligan” for “the gang” we have a good example of how important it is to locate deviant subjects within different periods of time and space to make sense of what Gilbert (1986) calls “cycles of outrage.” In Britain this tradition of critical social historical inquiry is prevalent in many of the social sciences and particularly in criminology, but it is less so in the United States where a preference for empiricism, presentism and positivism has generally negated the virtues of an historically grounded orientation.

Nonetheless, when we look at the gang in history we often see something akin to Pearson’s discoveries that compel us to take a second look at our assumptions. For example, in the discovery phase of a social group, the range of social reactions to a set of behaviors, the circumstances under which these behaviors are said to have occurred and the processes that are purported to explain the behavior’s emergence. Therefore, in addition to placing the gang in history, doing our utmost to reveal or at least consider the dominant discourses within which it is emerging, we need to contemplate the gang with history.

For example, in my previous work with Luis Barrios (see Brotherton and Barrios 2004) on the New York Latin Kings and Queens, it was impossible to consider this group in the present without a grasp of its historical development, its claims to history (e.g. it named its branches after ancient indigenous peoples in the Caribbean) and, in particular, its relationship to gang subcultures not only in the New York City area but also in Chicago and later in other cities outside the United States. We found that the language of the group, its style of organization, its codes of conduct and its ideology could only be explained within this historical framework. It was only after seeing the organization within history that we could begin to understand the range of meanings members were attaching to their group experiences and the developmental processes they were describing and we were witnessing.

Yet the study is fairly exceptional in contemporary gang research, where subjects are more typically portrayed as historyless with scant attention paid to: (1) processes of individual social development; (2) the origins of the group or subculture to which the individuals are affiliated; and (3) the long-term development of the community within which the subjects reside, i.e. their setting. Consequently, gang subjects are mostly located outside of any real matrix of dynamic, intersecting structures within which human beings achieve agency and strive to make sense of their lot. In this way, the gang becomes a thing-in-itself, a deviant subspecies made real and evidenced through certain properties with characteristics that researchers suggest contribute to the social reproduction of the lower classes (Miller 1958) at best, or the destruction of community life (Yablonsky 1963) or even Western civilization (Manwaring 2005) at worst. However, any examination of history reminds us that this process is highly contradictory, with the role of gangs in such socio-political processes neither predictable nor absolute, with accommodationist, oppositional and resistance behaviors mixed with individual agency, subcultural innovation and the rituals of conformity and non-conformity playing out in structured yet fluid environments.

Gangs and the community

One way to think about the gang both in history and with history is to understand the group and its members through the experiences of the community. Joan Moore3 in her study of intergenerational Chicano gangs in Los Angeles during the 1970s underscores the need for community context:

The barrios are Chicano by repeated external definition both in the past and continuously in the present. It is no accident that the 350 street murals of East Los Angeles are always built around Mexican and Indian themes. Or that the high schools of the area sponsor and train folklorico dance troupes who perform at many community functions with pride and with applause. “Cultural nationalism” did not have to be invented; it is normal and expressive in the life-patterns of the community itself. The daily, weekly, and yearly rhythms of life in the barrios differ from those elsewhere in Los Angeles. They are geared to a social system that emphasizes a ...