The idea that a more integrated administrative system improves government spans the twentieth century. Court reformers in the United States have advocated a unified structure, especially for the state courts, but for the federal courts as well. The central aim of reformers has been to consolidate all courts in a state into a single hierarchy under the supervision of a state supreme court. A true judicial branch would thus be constructed.

Consequently, the legislative branch would fund the courts apart from the executive branch or any local jurisdiction’s budget. The reform view also holds that the judicial branch should be staffed by judges selected on the basis of merit instead of on political partisanship. Coupled with the supervision of the state supreme court, the emphasis on merit-based professionalism suggests more effective court operations and judicial discipline than a decentralized, politically oriented system could produce.

Blease Graham introduces and catalogs the broad traditions of twentieth-century reform ideals. He identifies the “reform spirit” of late nineteenth-century American progressivism and connects Taylor’s scientific management and Weber’s ideal bureaucracy to the reform question. Simplicity and flexibility are the goals of scientific operations and a unified, centrally directed structure holds the promise of enhanced responsibility and efficiency. Whether or not the goals of reform are achieved has led to more and more concern about evaluating actual outcomes. Evaluations provide fertile evidence for political support or opposition to reform proposals and spur alternatives to elementary applications of reform principles.

Revisions of scientific principles and the prescriptive approach to management structures have resulted in a contemporary policy-oriented approach to court management. Philip Dubois and Keith Boyum pursue the policy debate in detail. They distinguish several types of court reform: judicial infrastructure, dispute management and case processing, and secondary or court-related reforms.

Judicial infrastructure issues deal with the basic organization, structure, and administration of court systems. The number and jurisdiction of courts, the judges assigned to them, and the selection, oversight, and removal of judges are key issues. The politics of court reform emerge from proposals for change in these areas. Court reformers also aim to improve the timeliness, efficiency, and economical management of legal disputes. Professional court administrators have been instrumental in better case processing. So have been attempts to reduce the flow of cases into the system through such nonadjudicative means as arbitration, mediation, or neighborhood justice centers. Court-related reforms include activities that have an effect on the judiciary apart from concerns about court operations or court efficiency; special treatment for drug crimes is an example. Throughout the discussion, Dubois and Boyum clarify why some policy changes have succeeded and why others have not.

Donald Dahlin supplies a progress report on exchanges between the normative model of the court reformers and the political realities promoted by opponents and critics. He offers a decentralized, consultative model and a contingency model as equally useful reform approaches. Among the insights generated by Dahlin is that there is no one best model of court organization and management. Also, Dahlin maintains that continued court independence requires a systems perspective on external relations, a centralized authority of some type, and the constant application of the wider management literature. The results will be increased emphasis on variables rather than models and increased efforts to collect data to assess the workings of relevant variables in court systems.

The chapters in this section illustrate the rich background and the current controversies in court reform. These controversies are not likely to be settled conclusively, but in the pursuit of court reform, advocates, analysts, scholars, and critics have opened paths for the ongoing development of a more productive and suitable court system.

I. Introduction: New Demands on Court Officers and Structures

Federal and state courts today are achieving increasing public recognition in the face of rising demands. For example, the New York Times refers to a federal district court judge 44who shuns robe and bench” as “innovative” (Lubasch, 1991, A14.1-5). The reported innovation may be more symbolic than substantive—this judge neither sits at the traditional judge’s desk or bench nor does he wear a black robe; he sits at a conference table and wears a business suit. The judge says that people should feel comfortable in the courthouse, yet his hallmark has become handling difficult cases, such as asbestos injury trust funds or compensation for persons exposed to Agent Orange while serving in Vietnam. The reporter notes that the judge is creative but that “higher courts have reversed him more often than one might expect for a judge of his stature” (Lubasch, A14:3).

State court judges are facing similar tides of complex legal challenges in the 1990s. Neal Peirce observes, with respect to environmental law cases

Instead of probate and property claims, their honors suddenly [find] themselves wrestling with basic hydrology and geology, site-evaluation issues, wetlands and site remediation—subjects rarely, if ever, taught when today’s judges were in law school (1991:1580).

He concludes that current state court administration practices, such as rotation of state judges, create problems for handling long-term environmental cases. As a consequence, there is pressure on states individually to reorganize courts so they will be able to handle, if nothing else, the actions of the more than 20,000 environmental lawyers in the country.

Environmental law is just one of many newly developing pressures for increased state court activities. A longer list includes illegal drug trade, children in poverty, increased percentage of elderly persons, poverty cycles, and weakening family structure (Zweig et al., 1990). The growth of such issues can be seen in the surge of specialty materials in law libraries and in the offerings of legal research services, which can be discovered, for example, through a look at the new topics in the Index of Legal Periodicals. These innovative issues and their complexity represent extensive new demands to reorganize and simplify existing federal and state court structures.

But the political realities of American federalism continue to dictate a dual national and state court structure. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor observes that our court system is a judicial federalism in which ‘‘federal law is in fact developed and interpreted by all 50 state court systems as well as by our federal courts’’ (1989:8). The administration of justice, through the administration of civil and criminal court cases, is “largely left to state and local governments” (Adrian and Fine, 1991:363).

Overall, the prospects appear ominous, since disorder and fragmentation, especially in state courts, may be dominant. Henry R. Glick observes that

state courts usually are loose networks of semiautonomous trial and appellate courts. Individual judges and court clerks have been free to manage their courts as they see fit, without much interference or direction from state supreme courts or court administrators (1982:17).

Other scholars and observers assert that state courts are the least changed branch today (Buchsbaum, 1989). But, state courts may also be understudied and overlooked centers of policy development (Baum, 1989). Indeed, it is possible that state courts are significant policy actors emerging from a long dormant period. State courts may, within a specific state on a specific issue, actually impose more rigorous standards than basic federal policy (Kincaid, 1988).

Today’s awakening state court structures face extraordinary levels of case activity that can lead to “hand wringing” (McLaughlan, 1991). For example, in 1989, the fifty state court systems, along with that of the District of Columbia, processed more than 17 million civil suits and over 12 million criminal cases, not counting 1.4 million juvenile cases or 67.2 million traffic or ordinance-related cases (Lazarfeld, 1991:3). With respect to capacity, federal courts have an equally heavy load. Federal district courts in 1988 handled 239,600 civil actions and 43,500 criminal cases (Statistical Abstract, 1990:183).

Increased or innovative judicial performance along with more fitting development of judicial skills are among the ways to deal with such heavy demands on court structures. But, court reform is more than innovation by a single judge in a specific court or improved performance by many judges in a new and difficult area of litigation. The reform and modernization of national and state courts in the twentieth century has focused primarily on the larger problems of reshaping structures and improving performance.

Federal and state courts are separate but related systems that are connected by constitutional developments, statutory provisions, and politics (Ball, 1980; Jacob, 1978). Reformers have promoted structural and management changes in both. Federal court reform issues have included better management of cases through increased numbers of judges, better realignment of districts, development of professional court managers, and the creation of special courts. Prevailing issues in each of the fifty state court systems include whether or not to add an intermediate appellate court, how to improve the office of state court administrator, whether or not to unify the judicial branch budget, and how to relieve caseloads (Bowman and Kearney, 1986).

Reform proposals have usually advocated a “systems” approach and have included extensive debate about structural redesign as well as procedural changes. Generally, these reforms have recommended court unification in the following specific ways:

Structural unification: consolidation and simplification of existing courts and development of specialized courts with respect to the new central court.

Administrative centralization: a single manager promotes uniformity in rules, assignments, and use of managerial personnel, as well as in financial matters.

Unified budgeting: a central budget at the state level gives all courts a resource base. If the budget is free from executive modification, then states have a more independent judicial branch (Abadinsky, 1991:165-169).

If realized over often strong opposition, these structural reforms should lead to improved performance. A more efficient, more flexible, more responsible implementation of state and federal judicial functions is the expected result.

The general background and selected aspects of court reform are discussed in the following sections of this chapter. The purpose of the discussion is to describe selected aspects of the reform tradition. This introductory chapter provides a general, illustrative overview and descriptive background for the detailed examination, analysis, and treatment in subsequent chapters.

II. Background for Court Reform

A. Pound’s Alarm Bell

The legal community first heard the alarm for court reform in Roscoe Pound’s 1906 keynote address to the American Bar Association (ABA; Pound, 1937a). While not an entirely new message, Pound’s remarks were shocking to many and challenged what might be termed “the genteel complacency of the established legal profession.” The criticisms in Pound’s speech sound like a lecture in the classical “principles” of public administration. He condemned fragmented court structures, duplication through concurrent jurisdictions, and wasted judicial resources. Pound’s reform proposals emphasized an improved, unified court structure along with administrative simplicity, flexibility, and responsibility. These general proposals reflect the “reform spirit” of American progressivism and apply F. W. Taylor’s “principles of Scientific Management” to the organizational and managerial problems of judicial administration.

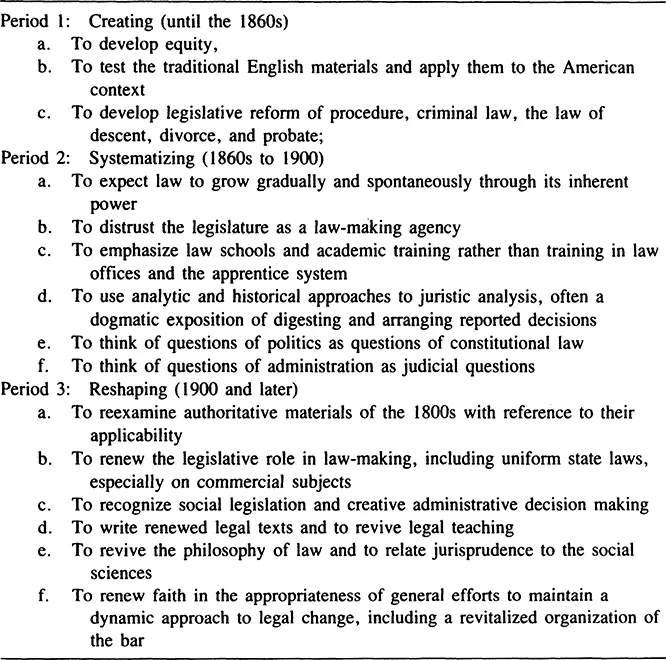

In a later work, Pound (1937b) recognized three general periods in the development of American law: (1) a creative period lasting to the Civil War, (2) a period of systematizing from the Civil War to the end of the century, and (3) a period of reshaping, destined to be a new creative era, since 1900. The major tasks and characteristics of each period are presented in more detail in Table 1.

Pound’s views were derived during a general period of reform politics in the United States. Reform concerns have affected virtually every aspect of American social and political life since the early twentieth century. Following in the next part is a broad discussion of this significant influence on American court structures.

B. The Reform Context

The political momentum for reform came from the Populists (Goodwyn, 1978; Hicks, 1961), who had practically disappeared by 1900, but whose principles were carried forward by Theodore Roosevelt’s Republicanism and W. J. Bryan’s Democratic ideals (Hofstadter, 1955). The new age of widespread political reform was more than the separate, populist movement of farmers; it was a broader aggregation of political interests, or progressivism.

Progressivism was backed in particular by urban middle classes as well as by many wealthy individuals and significant groups from labor. It was in part a reaction to the rise of big business after the Civil War and in part a reaction to growing labor unions and rising support for European socialism. Progressivism was a way to stop or moderate the significant new concentrations of power in business and unions while simultaneously preserving some political power for small business.

For the Progressive reformers, a proper role for government was to reflect the majority will and to break what they saw as the often corrupt hold of business on government. Generally, the Progressives believed that the state should intervene for desired social ends and not be a passive mask for hidden political powers. The state had to be a regulatory agency so that the small businessperson, the farmer, and the laborer could flourish. It had to be a protective agency so that women, children, and other groups in need in a “harshly competitive” world could also make their way.

Table 1 Dean Roscoe Pound’s Characterization of Major Periods in the History of American Law

Pound’s advocacy of a reshaped and reformed court system accommodated the reform movement’s idealism and zeal to court system architecture and operations. His opinions promoted the necessity for making the values of political reform and rational administration a political reality, even when legislators, executives, and fellow jurists ignored or disagreed with them.

C. The Foundations of Administrative Reform

Pound’s vision of court reshaping was more than a revived attitude for judicial decisionmakers; it was also a new court structure that had the capacity to manage the new, diverse, pathfinding workload of the reform agenda (Hays, 1978). A separate, scientifically oriented administration based on a rational structure ...