eBook - ePub

The Uncertain Mind

Individual Differences in Facing the Unknown

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Uncertain Mind

Individual Differences in Facing the Unknown

About this book

This book discusses individual differences in how people react to uncertainty. The authors show that while some people are relatively comfortable dealing with uncertainty and strive to resolve it (uncertainty-oriented), others are more likely to avoid uncertainty, preferring the familiar or the known (certainty-oriented). They go on to examine the implications of an uncertainty orientation for understanding processes of self-knowledge, social cognition and attitude change, achievement, motivation and performance, interpersonal and group processes, and issues relating to physical and psychological health concerns. Research is discussed which links this uncertainty orientation to each of these issues, raising important practical and theoretical questions for each. The book also considers possible implications for people of both orientations of living in times that may be characterized as being uncertain.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Uncertain Mind

The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers. -Erich Fromm

May you live in interesting times. -Curse from the ancient East

Uncertainty and Society

The twentieth century has been colored by the principle of uncertainty, taken both in its original Heisenberg meaning of 1927, to refer to a fundamental incommensurability, and in its broadest sense, as a general characteristic of the life of modern man since Einstein’s miracle year of 1905 and the killing of the archduke in 1914. Along with relativity, uncertainty is a sort of charismatic concept, exciting those who filter conventional concepts and data through its perspectives. (Fiddle, 1980, p.3)

The notion that uncertainty has become a major characteristic of the 20th century is borne out by numerous books and articles on the subject. The Library of Congress lists 725 books published from 1968 to 1997 with the word uncertainty as part of the title. These include books on uncertainty modeling, coping with uncertainty in the face of chaos, self-organization and complexity, uncertain motherhood, economics, dynamic timing, bargaining, trade reform, leadership, risk management and risk taking, environmental policy, medical choices, multidisciplinary conceptions, emerging paradigms, political science and science policy, and information and communication. In the discipline of psychology, the PsycLit 2 database lists 3,278 books, chapters, and journal articles published between 1987 and July of 1999 in which uncertainty is a key word.

It is no stretch of the imagination to envision concerns with uncertainty carrying over into the 21st century. On a broad scale, pressures toward globalization are challenging people’s notions of their group identity. Where people previously might have identified themselves ethnically or nationally, there are now pressures to broaden this perspective (exemplified best, perhaps, by the birth of the European Community and also reflected in various other trade blocks). Other major international changes setting an atmosphere of uncertainty have also been occurring, with the fall of the Berlin wall, the break-up of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, the return of Hong Kong to China coupled with the massive immigration of Pacific Rim people to North America, the nature of the relationship between Israel and surrounding Arab nations, and so on. In the face of these uncertainties, it is interesting to note a fairly strong tendency, at least for some, to reject new notions. The seeming increase in overt racism in Europe, extreme reactions against the peace process (including the assassination of an Israeli leader), tribal wars in the former Eastern block, and possibly a renewed support for communism in Russia may all reflect difficulties that many people seem to be having dealing with uncertainty.

In the Western world, and certainly in North America, there has been a “swing to the right” in recent years, a return to a more fundamentalist, authoritarian structure. This return may be a reflection of people’s hopes of controlling uncertainty wrought by globalization, industry downsizing or restructuring, national debt concerns, the immigration trends blamed for increased taxation, and limited resources for health and education, to name a few possibilities. In contrast to the many people in the so-called fabulous fifties, present-day North Americans no longer seem to feel assured of a safe and secure future. Many people’s parents and grandparents could expect to work at the same company as long as they wished, send their children to the schools they wanted (or at least get an excellent education for their children at minimal costs), own a house, and plan wisely and securely for their retirement. Those days are gone, and with them went the certainty that those who “did the right thing” would have a happy and secure future.

The swing to the right seems to come with government and various political parties promising to restore what they view as important values (such as “family values”), bring budgeting under control, cut services to new or illegal immigrants, cut taxes, and promote jobs. Not coincidentally, they often refer to the “good old days” of relative certainty and stability, either directly or indirectly. In the Canadian province of Ontario, one premier was elected with what he called his “common sense revolution.” In the United States, the Republicans won both houses of Congress for the first time in some 40 or 50 years with its simplistic “contract with America.” In California, severe legislation against the immigrant population was passed. In North America (as in parts of Europe), the “skinheads” have emerged as a neo-fascist and dangerous force against immigrants. It also seems that antigovernment and racist groups have gained popularity, increasing their support by people looking for simple solutions to complex problems.

When one thinks about these various issues of current importance, it is tempting to consider this era as relatively unique in the degree of uncertainty many people face, perhaps approximated in modern times only by the Industrial Revolution Era. During the Industrial Revolution, the nature of work changed for many people, and increasingly larger cities replaced smaller communities. Other examples may have been more specific to countries or regions, such as the economic uncertainty that seems to have characterized Germany following World War 1, and was possibly at least one factor that paved the way for Nazism.

Smith (1995) described issues such as these as a concern for the great majority of people, and saw the rise of postmodernistic, antiscientific views as emanating from a middle-class perspective (p.406). Here, as well, we see the concern with uncertainty as pervasive. He wrote,

As a middle-class intellectual, like most other social critics, I am most alert to features of our own middle-class-life world that threaten our morale—the prevalent cynicism about politics, indeed, about most social institutions; the shallowness of the mass media and the chaos of contemporary attempts at high art and literature; the inescapable climate of sensationalism focussed on sex and violence; the unnegotiable clash between fundamentalism and absolutism on the one hand and nihilistic relativism on the other; the uncertainty about all standards, whether they concern knowledge, art, or morals—or the utter rejection of standards; and the fin de siecle sense of drift and doom. It is the experience of the Euro-American elite that is evoked when we apply the label “postmodern” to our present predicament. (Smith, 1995 p.406)

Increasingly popular postmodern approaches that argue against absolutes pose challenges to the “certainty” of the scientific method itself! Uncertainty is thus a concept that reaches beyond the laboratory walls of academia, and is at the very heart of scientific concern. The suggestion that these myriad issues can best be understood in terms of uncertainty and people’s reaction to it may itself seem like a simplistic attempt at accounting for vast uncertainties. Indeed, people’s responses to uncertainty do not offer a complete explanation for all of these issues, but it seems that these responses indeed play a surprisingly important role in accounting for vast uncertainties. Subsequent chapters present evidence supporting the importance of dealing with uncertainty in determining what people do and centralize the importance of examining the different ways people handle uncertainty.

People’s ways of coping with uncertainty, which seem to form along a continuum, are referred to as their uncertainty orientation. At one end are those who find uncertainty a challenge. These people are called uncertainty-oriented because approaching and resolving uncertainty has become part of their way of thinking about the world. At the other end of the continuum are those who view uncertainty as something to be avoided. These are the certainty- oriented, who cling to the familiar, predictable, and certain as their ways of thinking about the world. What follows is a brief character description of each of our two exemplars.

Uncertainty- and Certainty-Oriented People

The Uncertainty-Oriented Person

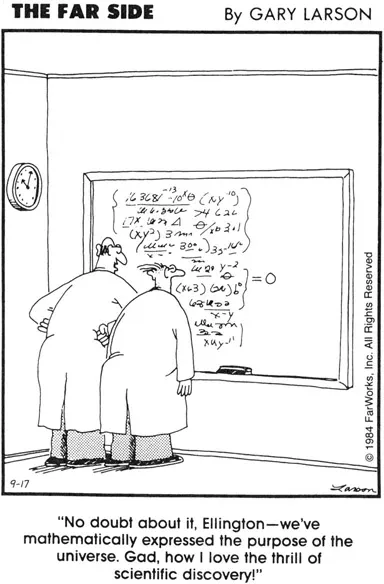

Figure 1.1 is a caricature of an uncertainty-oriented (UO) person. In this cartoon, the two scientists are excited by a new discovery—the meaning of the universe. Although they have proven mathematically that the universe is meaningless (i.e., = 0), they are nonetheless thrilled that they have resolved the ultimate uncertainty. What is important to them is not how this information makes them feel (referred to as affective value of information); all they care about is that they have resolved the uncertainty. This caricature captures the essence of the UO because UOs are driven by what there is to be learned from a situation. To the extent that a situation provides new information or resolves uncertainty about their ability, opinions, and understanding of the world, UOs are motivated to think effortfully and to act vigorously. This means that UOs have a positive orientation toward novel or uncertain situations; to them these situations can be seen as an opportunity to learn something new about themselves or about the world.

From a psychodynamic perspective, one might view the UO as one who likely made it through the oral, anal, and phallic stages of development relatively successfully, thus developing a basic trust in the world, a sense of autonomy, and a desire to explore new worlds (see Erikson, 1959). From a social cognition perspective, one might view this person as one who developed a self-regulatory style of uncertainty resolution and who resolves uncertainty by mastering uncertain situations. As yet, the uncertainty-orientation literature has provided no hard data to support either perspective, but from either, this person is seen as being oriented toward learning about the self and the environment. The UO accesses situations that offer information. The UO is the “need-to-know” type so readily advocated by rational or Gestalt psychologists. Anything dealing with the process of understanding, particularly understanding of the self or the self in relation to others, is important to this individual. Self-assessment, social (and physical) comparison, causal searches and attributions, possible selves, self-concept discrepancy reduction, self-confrontation, social justice, and equity are all common characteristics in this person. Because the UO is open to new beliefs and ideas, he or she is likely to be tolerant of others, regardless of race, color, creed, gender, or ethnic background.

FIGURE 1.1. A caricature of the uncertainty-oriented person. THE FAR SIDE © 1985 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Although the UO is one who approaches uncertainty (i.e., wants to find out new things and achieve understanding of the self and the world), he or she is not without affective needs, desires to attain, or fears to avoid. This person may wish to succeed or be loved and wanted in order to feel good or may wish to avoid failure or social rejection in order to avoid feeling bad. Power, materialism, approval, control, and sexual gratification are also needs that may vary in strength and will operate in conjunction with the relevance of uncertainty for the UO. As is discussed later, both one’s desires and one’s fears are greatest in uncertain situations—those situations that are most important for the UO. If the UO is also success oriented, then it is success in uncertain situations that will be most positively motivating for this person. However, if the person is also failure threatened, then it is failure in uncertain situations that will be most negatively motivating (i.e., anxiety and fear evoking) for that person. This would work for any other positive or negative source of motivation and adds a great deal to the complexity and multiply determined behavior of the UO. Motives do not operate in a vacuum, nor do personality dimensions act by themselves.

The Certainty-Oriented Person

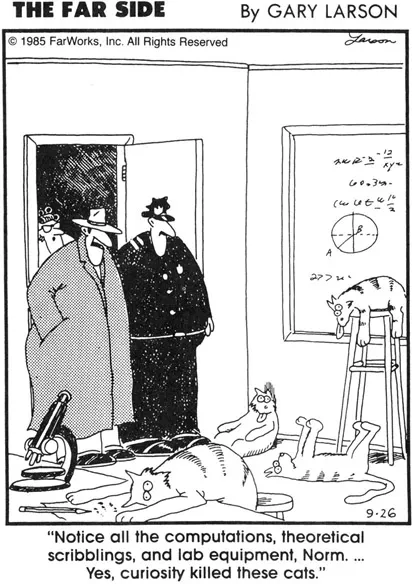

Figure 1.2 is a caricature of the certainty-oriented person (CO). In this cartoon, the detective is telling the police officer that “curiosity killed these cats.” The expression curiosity killed the cat, which appears to be unique to North America, is similar to the Northern Europe, “If you put your nose too close to the pot it could get burned.” Both of these sayings suggest that curiosity or inquisitiveness is bad. It does not matter what the affective value of the information is likely to be. Whether one could feel good or bad about some information she or he might discover, all this person cares about is that she or he should not look in the first place. In other words, one should not try to resolve or deal with uncertainty.

FIGURE 1.2. A caricature of the certainty-oriented person. THE FAR SIDE © 1984 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Although this cartoon is a caricature of what is conceived as the CO personality, its caption captures the essence of the CO person. For COs, it is certainty and maintaining clarity that is important, and confusion and ambiguity are to be ignored or avoided. Thus, to the extent that a situation provides familiarity and certainty about their ability, opinions, and understanding of the world, these people will be motivated to think eflortfully and to act vigorously. From a psychodynamic perspective, the CO likely did not make it through the oral, anal, and phallic stages of development very successfully. Consequently, this person developed a basic mistrust in the world, a lack of a sense of autonomy, and a desire to adhere to predictable and familiar worlds. From a social cognition perspective, the person may have developed a self-regulatory style of uncertainty avoidance. This involved only attending to basic rules or fundamental laws of human behavior that will help avoid uncertainties in one’s life. What is important from either perspective is that this person is oriented toward maintenance of present clarity about the self and the environment. This person assesses situations that offer no new information (and thus do not threaten potential confusion). COs typify the psychodynamic type so close to Freudian or psychoanalytic views of personality and so readily dismissed by rational or geslalt psychologists. Again, it is only a different style of self-regulation. Anything dealing with the process of understanding, particularly understanding of the self or the self in relation to others, is ignored by this individual. Self-assessment, social (and physical) comparison, causal searches and attributions, possible selves, self-concept discrepancy reduction, self-confrontation, social justice, and equity are all characteristics that this person has little concern for. Because the CO is closed to new beliefs and or ideas, he or she is likely to be intolerant of others who are different (or appear to have different beliefs) with respect to race, color, creed, gender, or ethnic background.

Although we can think of the CO as one who finds certainty relevant (wanting to adhere to what is already known or understood about the self and the world), he or she is not without affective needs, desires to attain, or fears to avoid. Just like the UO, he or she may wish to succeed or be loved and wanted in order to feel good or may wish to avoid failure or social rejection in order to avoid feeling bad. Power, materialism, approval, control, and sexual gratification are also needs that may vary in strength and will operate in conjunction with the relevance of certainty for the CO. One’s desires and even one’s fears are greatest in certain situations—those most important for the CO. If the CO is also success oriented, then it is success in situations of certainty that will be most positively motivating for this person. But if the person is also failure threatened, then it is failure in situations of certainty that will be most negatively motivating for that person. This would work ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Uncertain Mind

- 2 The Uncertain Mind and Self-Identity

- 3 The Uncertain Mind in Thought

- 4 The Uncertain Mind in Action

- 5 The Interpersonal Context

- 6 Health and Uncertainty Orientation

- 7 The Uncertain Mind: Looking Back and Moving Forward

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Uncertain Mind by Richard M. Sorrentino,Christopher J.R. Roney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.