![]()

Part I

The context of global leadership

![]()

1 The rise of globalization

Recently, one of the authors (Stewart Black) was giving a presentation on global leadership, and during the Q&A session, someone from the audience asked, “When did all this globalization start?”

Feeling a bit feisty, Stewart responded with a question of his own, “Do you want an approximate point in time or do you want the day, month, and year?”

Not to be outdone, the participant emphatically replied, “Day, month, and year, please.”

How would you answer this question? When did globalization start? Ten years ago? Twenty years ago? Fifty years ago? Is there a single event and date to which you would point as the beginning of globalization?

Without hesitation, Stewart replied, “Globalization began on the sixth day of September, 1522.”

“September 6, 1522? Where did you come up with that date?” queried the persistent participant.

“That was the date on which the surviving 18 men of the original 237-member crew of Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition arrived back in Spain, after circumnavigating the globe for the first time in the history of mankind,” Stewart concluded. Or so he thought.

After the session was over, a different participant came up and offered an alternative start date of globalization. He argued that, while it was true that Magellan was the first to circumnavigate the world, Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, the father and uncle of Marco Polo, opened the world up to systemic international trade in 1260 with their travels to and trade with Asia over 250 years before Magellan. “Marco Polo then subsequently built upon the pioneering trade routes of his father and uncle but he got most of the credit and fame,” the participant concluded.

Whether one points to the first circumnavigation of the globe by Magellan or the major international trade expeditions by the Polos, the key issue is that globalization has been going on for some time—arguably for centuries. Given that globalization is, in principle at least, not new, several questions spring to mind:

• If globalization in principle is not new, is there anything new and different under the globalization sun today? Or are the pontificating globalization gurus just trying to put old wine in new bottles?

• Assuming that there are in fact some things that are new and different about globalization today versus the past, why should we care about them?

• Assuming that there are compelling reasons to care about the new aspects of globalization, what does it take to be an effective global leader today and tomorrow?

• Assuming that there are certain capabilities that can indeed make one more or less effective at global leadership, how can we systematically develop those capabilities in ourselves and others?

For us, these are not just idle questions. Rather they have been the driving force of our research and consulting for nearly two decades. As a consequence, they are the core questions that we will address in this book—but not all in this first chapter. In this first chapter we take on the first question: What’s new about globalization today versus the past? In Chapter 2 we address the second question: Why should we care? In Chapters 3–7, we address the question: What does it take to be an effective global leader? In Chapters 8–10, we examine the question: How can we systematically develop ourselves and others to be effective global leaders? As we will explain in more detail in Chapter 3, the answers to these questions across all the chapters of this book are based on years of systematic field research which we have conducted, and on a combined experience base of over 50 years working as consultants with companies and their senior leaders trying to understand and meet the challenges of globalization and global leadership. On the basis of this significant base of research and practice, we hope that you will find the answers to these key questions both rigorous and relevant; we believe you will.

Common globalization path

In addressing the question of what’s new under the globalization sun, we have developed a simple but robust framework that helps put globalization in context. While on a micro level the details of every company’s globalization journey are unique, at a more macro level our research shows that there is a general development path that many, if not most, companies follow. The simplicity and power of the framework and the commonality of the path stem from the fact that there are two fundamental mechanisms by which all companies can grow outside their home market.

First, companies can move things (e.g., components, products, knowledge, people, etc.) from one place to another to create and capture value. For convenience, we label this movement “trade.” For example, you can make a product in one country and sell it in another. Or, as another example, you can take a leader from France and move her to Singapore where she can apply her skills and capabilities in the new location and create and capture value for you there.

Second, companies can make financial investments directly in a foreign locale to build up capabilities there. For convenience, we label this activity “investment” or “foreign direct investment (FDI).” For example, you can invest in building a factory or a service center in a given country. As another example, you can invest time and money identifying and building up leadership capabilities in a given locale.

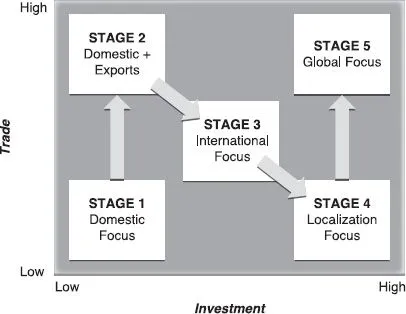

Each of these two mechanisms (i.e., trade and investment) constitutes an axis in a two-dimensional model. The two dimensions are conceptually independent and do not need to move in unison or in opposition. Therefore, companies could emphasize or deemphasize each dimension to any degree and in any sequence they wanted. Despite this independence and a myriad of possible paths and sequences, it is interesting that the majority of companies follow a common path through this two-dimensional space. As we examined the common pattern across companies, we discovered that it did not happen by accident but was the outcome of common economic and psychological drivers that were strong enough to largely trump industry, country, or even company differences. The outcome is a 5-stage path to globalization depicted in Figure 1.1. In the subsequent subsections, we describe the nature of each stage and the drivers that tend to move companies from one stage to the next.

Stage 1: domestic birth and focus

Until recently, it was virtually impossible for a firm to be born global. Instead firms were born or started in a given country and usually spent much of their life, and certainly their early life, in their “birth country.” To appreciate this, you only need to look at today’s largest firms. Most were born 30, 40, and some over 100 years ago. For example, if you take the Fortune Global 500, which is a list of the largest 500 companies in the world by revenue, virtually every one of them started in a particular country and started there many decades ago. For example, General Electric (GE) was born in the United States in 1892. Michelin was started in France in 1888. Toyota was founded in Japan in 1937. Siemens was established in Germany in 1847. Nokia was born in Finland in 1865. Even 50 years after each company was started, every one had more than 80 percent of their assets and employees based in their home market.

Figure 1.1 Five stages on the path of globalization

In their early days, these and most companies focus on competing and growing at home. After all, if you don’t focus on competing where you are born, you are unlikely to survive long enough to compete, let alone thrive and grow, somewhere else. However, as companies focus on their home market and are successful there, they can start to run into growth limits. For example, if you are a top executive at Gillette and after 50 years of growth since the company’s founding in 1901 you have 70 percent of your home razor market and you still want to grow, it is natural for you to think about expanding internationally and therefore consider moving out of Stage 1. In fact, the faster company executives want to grow the firm and the smaller the home market, the greater and the earlier the catalyst to leave Stage 1. However, even if the company resides in a country with a large domestic market, eventually, as the home market matures and saturates, growth rates decline. Granted, to reach this point of diminishing growth can take decades. For example, GE spent its first 80 years primarily focused on its domestic market with more than 90 percent of its sales coming from the United States. If company executives are content with and accept declining growth rates, the company could stay in Stage 1 indefinitely. However, most company executives, especially those of public companies, are not willing to accept these declining growth rates, and so they start to think about leaving Stage 1.

Stage 2: export focus

If it is accepted that growth rates at some point are likely to stall out and then decline if a company just stays in Stage 1, why do most companies typically move from a domestic focus to exports? Why don’t they jump straight into making big investments in foreign markets? In our research, we found that there are two principle forces that move most companies from Stage 1 (domestic focus) to Stage 2 (exports). One force is mostly grounded in economics and the second primarily in psychology.

Economic drivers

The economic driver of movement from Stage 1 to 2 is fairly straightforward. For manufactured goods with any degree of economies of scale, it just makes economic sense to get full utilization out of existing capacity, capture the economies of scale, lower per-unit costs, increase margins, and make more money by exporting. However, we need to stress that for most firms, the increased profits do not primarily come from the exports themselves. Yes, exports bring greater revenue and with that hopefully increased profits. However, the greatest capture of the increased margins due to the greater capacity utilization and economies of scale that exports provide is in domestic sales. For example, when Toyota started to move into exports in the early 1960s, domestic sales were five times greater than exports. Therefore, the increased capacity utilization and enhanced margins that exports provided to all the cars Toyota produced had their greatest benefits for cars produced for domestic sales, which as we mentioned were five times those of cars produced for exports.

Conversely, if Toyota had gone straight to building a factory abroad, say in the United States, for example, the economies of scale, capacity utilization, margin benefits, etc. could not have been applied to or captured in Toyota’s domestic sales in Japan; they would have been limited to the production and sales out of their new factory in the United States. This is partly why Toyota didn’t invest in building a car factory outside of Japan for more than 25 years after it started exporting cars. As we already pointed out, early in the process of moving out of Stage 1, domestic sales are always larger and usually much, much larger than international sales. Therefore, moving from Stage 1 directly into Stage 3 or Stage 4 by investing directly in foreign markets typically doesn’t make as much economic sense as going for exports (i.e., moving into Stage 2). In addition, unless your products have a terrible weight-to-value ratio, such as bricks or cement, the savings captured through economies of scale typically are much larger than the shipping and other transaction costs associated with exporting. As a consequence, exports not only allow you to win the big prize of capturing the economy of scale benefits on domestic sales but also enable you to make money on the exports themselves.

In addition to the economic incentive to capture returns via the economies of scale on tangible assets like plant and equipment, there are also economic incentives to capture returns on economies of scale related to intangible assets. For example, after years of working and succeeding at home, a company typically builds up intangible assets, such as knowledge of and relationships with existing suppliers, employees, regulators, and the like. Exports in Stage 2 allow you to leverage those intangible assets and thereby enhance your return on investment (ROI) relative to the investments you have put into building up those intangible assets. To put it more simply, exports increase your ROI on intangible domestic assets because exports give you increased revenues without having to make much new investment in your intangible assets.

If we return to our example of Toyota, in addition to already having the plant and equipment to make cars at home in Japan for export to the United States and elsewhere, it already knows and has relationships with its workforce. Those workers know the Toyota way of manufacturing. Toyota already has relationships with suppliers and its suppliers know how to work within the “Toyota Way.” To make more cars for export, Toyota doesn’t really need to make any new investments in these intangible but very valuable assets. The numerator (i.e., revenues) goes up without much increase in the denominator (i.e., investments in intangible assets), and therefore the return improves. It is simple math that any executive can understand and is naturally incentivized to pursue.

In contrast, if Toyota moved out of Stage 1 by building production capacity in the United States, it would have to make significant investments not just in tangible assets like plant and equipment but in intangible assets as well. For example, it would have to invest time and money into figuring out how to effectively work with U.S. autoworkers and their unions. Given that the structure and orientation of U.S. autoworker unions are quite different from Japan’s, Toyota would have to invest significant time and money into building up the intangible asset of understanding and working effectively with U.S. autoworker unions. This increased investment actually delivers a double negative effect. First, it causes Toyota to lose out on the ROI benefits of leveraging existing investments into its intangible asset of good working relations with Japanese unions that exports would have provided. Second, the greater this increased investment into understanding and working with U.S. unions, the lower the near-term ROI relative to its expansion in the United States and, all other things being equal, the longer it would take Toyota before it passed the breakeven point on those investments.

Thus, leaving one’s home turf (Stage 1) via exports (Stage 2) for Toyota and many, many firms provides a much better ROI (especially early on) than leaving via the other alternatives (i.e., Stage 3, 4, or 5). Bottom line: exports can cut per-unit costs and grow revenues and profits all at the same time by leveraging both existing tangible and intangible assets. Therefore, moving from a domestic focus next to e...