![]()

1

POLITICS OF SPACE

Space is a social morphology; it is to lived experience what form itself is to the living organism, and just as intimately bound up with function and structure.

Henri Lefebvre 1991, 94

The limits of possible spaces are the limits of possible modes of corporeality: the body’s infinite pliability is a measure of the infinite plasticity of the spatiotemporal universe in which it is housed and through which bodies become real, are lived, and have effects.

Elizabeth Grosz 2001, 33

Entering into the worlds of public education in Los Angeles after many years’ absence, I navigated the spaces as a stranger. Often I did not know where to enter, what the protocols were for passing security desks and gaining clearance, where my informants or interviewees were located, or how others would respond to my intruding presence. This outsider vantage point made for frequent uneasiness on my part, but it rendered these sites productively strange to me, for as a body negotiating terrain for the first time, I was acutely aware of symbolic ambiguities, sonic and visual disruptions, and physical obstacles to movement. At each of the dozen schools I visited, from elementary to middle to high schools, I interviewed technology coordinators and had them walk and talk me through (or around) their many technological infrastructures in progress: server rooms, trenches, repair areas, classrooms, computer labs, phone rooms, libraries. Throughout these tours, coordinators would comment on the archaeology of networks in those particular schools, short- and long-term goals, administrative and/or teacher opposition, construction mishaps, contractor disappearance, and, without exception, the politics of the Los Angeles Unified School District. I would take pictures of rooms, watch people interact and bodies flow through spaces, and talk with students, teachers, and administrators. The recurring referent was that of flux, of new socio-spatial orders merging with older ones and of people’s contributions and responses to these alterations.

The dominant architectural leitmotif of most schools in L.A. Unified, some well over a hundred years old, is that of discipline, order, containment, and standardization. These schools are concrete edifices, surrounded by fences (some with barbed wire), and divided into box-shaped classrooms, which contain neat rows of desks or tables, often bolted to the floor. This style is not surprising given the historical and political motivations behind the compulsory schooling movement that inspired the construction of such schools. By 1900, most states had passed compulsory education laws in an attempt to “Americanize” the 18.2 million immigrants who arrived between 1890 and 1920 (Sokal 1987; Brown 1992).

In conjunction with the introduction of psychological aptitude tests, school architecture injected an ideology of scientific rationality (e.g., standardization and differentiation) into education, intended to sort and tame bodies with the goal of combating the perceived risk of anomie that “uneducated” foreigners represented (Chapman 1988). The history of compulsory education can also be read as a positive, progressive effort to include and provide for all students irrespective of their differences or backgrounds. The point of discussing compulsory education here, however, is to comment on how ideologies and rationalities become embedded within built form. Thus, even if one celebrates the inclusive mission of compulsory education, the architectural manifestations remain those of standardization and compartmentalization: every student has a place, but all are also intended to remain in those places.

This older school model, which continues to serve as an architectural template for newer schools, can be linked, without too much strain, to another prominent institutional order that emerged in the early twentieth century: Fordism. Characterized by mass production, mass consumption, vertical integration, standardization, and the interchangeability of parts and workers (Amin 1994; Abu-Lughod 1999), Fordism encapsulates an ideology of rigid economic efficiency that penetrated deeply into private and public domains, such as industry and education.1

If one can judge the promise of the current information technology (IT) “revolution” by its surrounding rhetoric, it is, by contrast, uniquely post-Fordist. IT pundits such as Nicholas Negroponte (1997) proclaim: “Being digital has three physiological effects on the shape of our world. It decentralizes, it flattens, and it makes things bigger and smaller at the same time.” This sentiment is echoed in the media and then rearticulated by those in public institutions like L.A. Unified. For instance, in an interview with a mid-level technologist in the district, he opined:

A society that doesn’t integrate technology, be it industrial or third world, will be a third world society in a matter of a few years…. Where in our society, education has typically been patterned on an industrial model — kid walks in door, spends time, and kid leaves door…. Now what we’ve done is that we have technology that can distribute any kind of education, no matter how sophisticated, to anyone, anywhere in the world, at any time. So what we’ve done now is we’ve said, (a) you don’t have to have money to go to college and get educated, (b) even if you live in the highlands of Ireland and you’re still driving around a donkey and a cart, you can get information to do brain surgery if you need it. So the whole concept of education, delivery of knowledge, and thus producing educated individuals, is now suddenly free for all …. So the whole level of how much you need to know and how fast information changes has accelerated beyond a pace that’s ever been known in history.

These proclamations are post-Fordist in that they espouse a technology-driven change in production concepts and models, away from standardized mass-production and toward specialized just-in-time production, away from geographical boundaries and toward global distribution, away from temporally bounded creation processes and toward rapidly accelerated innovation, away from centralized organizations and toward decentralized collaborative entities, away from a producer paradigm and toward a consumer orientation. As with many similar articulations, these quotes by Negroponte and the district technologist imply that if such changes are embraced, they will lead to universal prosperity, democracy, and equality.

In contrast, many scholars question the presumed benefits of post-Fordism and its globalization context, saying that it is most likely a deleterious extension of capitalism rather than a departure from it, and that it leads to increased disparities between social groups rather than establishing conditions of mutual advantage (e.g., Harvey 1990; Castells 1996; Graham & Marvin 2001). For the present purposes, I would like to put this argument on hold and instead investigate how these two production models (Fordism and post-Fordism) — whether virtual, real, or both — clash, intermingle, and integrate in spatial forms, on the ground, generating new social relations and subsequently shaping the future in unanticipated and unforeseeable ways.

The integration of Fordist and post-Fordist production models in public education is really one of ideological synthesis, where the built world functions as a stubborn palimpsest, a continuously rewritten script whose previous lines, directions, and motivations can never be completely effaced. In this chapter, I observe these clashes through two lenses. First, ideological changes are read through the practices of students and teachers in existing technology classrooms. These snapshots of people in school spaces reveal the continuous reconstitution of mostly static, already constructed spaces, where the actions (and nonactions) of new occupants and new mentalities intermingle with sedimented materialities and institutional histories. I develop the concept of built pedagogy to account for the politics of spaces and their capacity to teach individuals how they should act in the world. Second, ideological changes are perceived through the ongoing redesign of educational spaces by school-site personnel. The process of integrating new information technologies into older school spaces highlights problems of material resistance to technologies that are often celebrated for their flexibility and virtuality.

Recognizing that spaces of education are spaces of cultural reproduction, I next argue that the pressures of globalization, including the valuing of compliant students and workers, are quietly reinforced through material impositions on social development and exchange. In answer to this trend toward self-flexibility demanded of actors in the system, a model of structural flexibility is proposed for the design of polyvalent spaces that empower rather than discipline their occupants.

Syncretic Spaces

The Fordist-informed design of older schools and classrooms makes the integration of IT a difficult endeavor in many ways. As computers and their networks are introduced into classrooms that previously had no machines, they are typically placed along the back and side walls. This design is chosen for purposes of providing easy, safe, and inexpensive electrical and data supply but also so as not to intrude overmuch into the existing territory of classrooms. As a result of these and other social reasons (see Chapter 2), computers are not often incorporated into daily classroom instruction. In other spaces that have previously housed machines, whether computers or typewriters before them, the design layout significantly departs from this periphery model, and computers are centrally deployed on tables lined up in neat rows across the room. The first space that I describe matches this latter layout of centralized computer placement.

Space 1: Computer Classroom at a High School

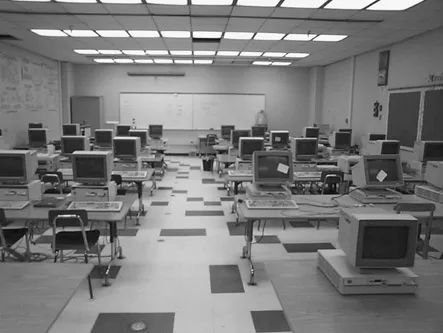

Tucked away behind lockers and colorful student wall murals on the second floor of the high school, this computer classroom is completely devoid of any windows or adornment; it is spare in spite of its relatively large size of roughly 26 by 40 feet, with room for forty students (Figure 1.1). Fluorescent lights glare from above, giving all bodies a yellowish tint, and sounds are muffled as they bounce off the scuffed floor tiles and up into the pockmarked drop ceiling. A sink area in the back of the room indicates a past life for this space, possibly as an arts-and-crafts room or science lab. There are two columns of tables, divided into five rows, with a protective barrier of desks and tables at the front of the room insulating the teacher from the students. All the tables are bolted to the floor to prevent their movement, and several big gouges in the floor tiles betray the destructive results of attempts at bolt removal. Awkwardly, metal-coated power outlets rise out of the floor like symmetrically planted land mines, serving as infrastructural traces of a past technological revolution: the electric typewriter.

The African American teacher in this room laconically greets his mostly Latino students by name as they wander in, and judging from their interchanges, they seem to have a good rapport. Students chat a little in Spanish or hum as they work on their lesson of transcribing a business letter; they peck along with one or two fingers while the teacher remains

Figure 1.1 Centralized computer layout.

mostly concealed behind his barricade of furniture. Occasionally students will get up and wander over to their friends to help them with their work; in order to occupy himself, the teacher removes a large pink feather duster from inside his file cabinet and dusts off the tops of unused machines. Midway through the period, one student coaxingly asks him if it is wrong to have someone else type the drill for him, to which the teacher responds: “Don’t play me like that; I can tell whether you typed it or not too.” With the ice broken, students ask the teacher whom he voted for in the 2000 presidential elections held the previous day (the results being still in dispute). His response: “A person.”

“Which candidate do you think is a better person?” the students press on.

“Ralph Nader, but I didn’t vote for him.”

“Yeah,” students pick up the drift, “only white people and rich people vote for Bush.”

He carefully corrects them, “Conservatives vote for Bush.”

“I want another Clinton,” a male student interjects.

“That’s why Gore didn’t win,” the teacher closes the conversation.

In this exchange, the teacher’s guarded enunciations transmit and mutually reinforce the signals of temperance and caution radiating out from this fortified space; just as the protective barrier of desks distances the teacher from the students, so does his control over the discussion keep personal divulgence and student connection at bay. The space provides a social script for him (and the students) to follow.

As I converse with the teacher after class, it is clear that he feels constrained by the typing-class layout, a remnant from another era. He confides that a cluster configuration would be much better for student collaboration and visibility (since they are now hidden behind monitor screens) and that he thinks other teachers would agree with him and be comfortable with a cluster design. I detect from his tone that he thinks I might have some leverage to make such changes occur, perhaps because I am frequently seen with the school’s technology coordinator and seem to have his confidence. The obstacles to rearranging a room, however, are severe: there is no budget for new furniture, only for new computers; the floor would likely be destroyed in the process of unbolting the existing tables; a new floor could be requested from L.A. Unified, but it would probably take a year or more before it was actually installed; and the labor would be a strain on the school’s limited technology staff of teaching assistants. Regardless of what the teacher says, he seems very comfortable with his current configuration, which grants him symbolic authority over the space.

Space 2: Computer Classroom at a High School

At a high school just outside of downtown Los Angeles, close to where several freeways merge in a maze-like, spaghetti-junction mess, I attend a meeting of technologists after school hours. During a break in the meeting, I take to wandering the halls, where I spy an older Latino teacher working alone in his computer classroom and decide to approach him. He explains to me the evolution of network installation at the high school and, indirectly, of his classroom. The district was using funds from a local bond measure to wire the school, but when contractors accidentally drilled into asbestos, the school had to be closed for 2 weeks of cleanup. Construction then stopped altogether for 9 months while contractors and the district fought over who should be held responsible for the added expenses and potential lawsuits. It took more than a year from the initial health alert for the network to be completed and its ownership to be signed over to the school.

The teacher had a fair degree of autonomy in choosing the actual layout of the room, and he elected to make the “side” of the classroom into its “front,” so that it could contain three long rows and two columns, with an aisle down the center (see Figure 1.2 for a picture of a similar space, not the actual room described). The effect of this configuration is increased visibility: the students can see the teacher and television screens up front without too much strain, and the teacher can easily walk to the back of the three rows and view every student’s monitor screen with one quick glance. Monitors face away from the windows at the front of the room, dissipating any glare problems from the external light. The teacher demonstrates the Apple Network Administrative Toolkit (ANAT) that he has running on the 30 networked computers in the room, showing me how he can “take control” of all the machines at once, a smaller grouping of them, or an individual workstation from his terminal at the front.

Figure 1.2 High-visibility classroom.

Moreover, if he so chooses, he can view the image of any student’s monitor on his computer screen without the student’s awareness and without disrupting his or her activities. The idea behind such technological control is augmented pedagogical attention, not discipline, he stresses, although ANAT can be used that way. My interlocutor confesses that such virtual monitoring is way too cumbersome, so he opts for “walking the aisles” instead.

The teacher continues to explain that this space is designed for instructional activities, lessons of leading and following, rather than those of self-exploration or collaboration. All the same, he does encourage students to engage in the kinds of collaborative projects that would be better served by a cluster arrangement of desks and machines, and he says that students have no problem getting up and walking over to others to see what they are doing and asking them how they are doing it. The range of student activities is determined by the tone of the instructor, he avers, and I agree, but the room does afford wandering and collaboration by means of its spaciousness (it is about the size of the first room described yet contains only one-quarter the number of computer stations and seats).

Space 3: Applied Math and Science Academy at a Middle School

An old wood shop at an L.A. Unified middle school has been converted into a multimedia classroom, and the room’s spaciousness and high ceilings provide a sense of ease and mobility (Figure 1.3). The layout resembles a plus sign (+), creating areas for separate tasks without rigid boundaries. Modular technology stations line the perimeter, leaving the center open for students to work on projects or walk between stations. Ten square tables are set up in this center area; their shape was specifically chosen, I am told, to create a defined sense of shared territory and to discourage too much wandering. (Rectangular tables were attempted first but were too bulky; round tables were tried second but encouraged too much movement.) From this center area, I can easily observe what students a...