Chapter 1

Introduction

Working in a stressful environment increases the risk both of suffering physical illness or symptoms of psychological distress (Cooper and Cartwright 1994; Cooper and Payne 1988), and also work-related accidents and injuries (Sutherland and Cooper 1991). The substantive body of well-documented research evidence supporting a causal relationship between working conditions, both physical and psychosocial, and individual health and well-being, has legitimised the concept of stress-induced illness and disease. Although it has received less academic interest, there is also research evidence supporting causal links between stressful working conditions and greater accident involvement in various contexts, including company car drivers (Cartwright et al. 1996), transit operators (Greiner et al. 1998), medical practitioners (Kirkcaldy et al. 1997) and veterinary surgeons (Trimpop et al. 2000).

In an increasingly litigious society, recent years have seen a growing number of ‘cumulative trauma’ compensation claims against US employers (National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) 1986); Karasek and Theorell 1990), and later, a number of successful personal injury claims in the United Kingdom (Earnshaw and Cooper 2001). The concept of ‘cumulative trauma’ relates to the development of mental illness as a result of continual exposure to occupational stress; the California Labor Code states that workers are entitled to compensation for disability or illness caused by ‘repetitive mentally or physically traumatic activities extending over a period of time, the combined effect of which causes any disability or need for medical treatment’. In the United Kingdom, the legal implications of stress-induced personal injury were highlighted by the landmark case of Walker v Northumberland County Council (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 The John Walker case

John Walker worked for Northumberland County Council from 1970 until December 1987 as an area social services officer. He held a middle-management position and was responsible for four teams of social services fieldworkers in the Blyth Valley area. Mr Walker was responsible for allocating cases to teams of field social workers and for holding case conferences in respect of children referred to his area of the Social Services Department. During the 1980s the population of Blyth Valley rose, leading to an increase in the volume of work to be undertaken by Mr Walker and his teams, but there was no corresponding rise in the number of fieldworkers. Mr Walker and his teams were increasingly under pressure, and this, of itself and apart from the stressful nature of the work, created stress and anxiety.

Between 1985 and 1987, Mr Walker repeatedly complained (in writing) to his superiors, expressing the need to alleviate the work pressure to which he and his social workers were subject. Mr Walker requested a redistribution of resources from rural areas to urban areas, such as his own. In November 1985, Mr Walker told his superior, Mr Davidson, that the Blyth Valley area should be split in two, and that he did not think he could go on shouldering his then volume of work. Mr Davidson told Mr Walker he was unwilling to make changes at that point, because within two years there was to be a restructuring of social services in the county. Mr Walker indicated that in that case he could go on, but he could not go on beyond two years. During 1986 the workload continued to increase and in November 1986 Mr Walker suffered a nervous breakdown.

In March 1987, Mr Walker returned to work, having negotiated for assistance to be provided for him on his return. However, support was provided only on an intermittent basis and was withdrawn by early April. During his absence a substantial backlog of paperwork had built up, which took Mr Walker until May to clear. In the meantime the number of pending cases continued to increase and Mr Walker began to experience stress symptoms again. By September 1987 he was advised to go on sick leave and was diagnosed as affected by a state of stress-related anxiety. He suffered a second mental breakdown and was obliged to retire from his post for reasons of ill-health.

Source: adapted from Earnshaw and Cooper (2001).

The judge held that the council was liable for Mr Walker’s second nervous breakdown, but not for his first. In this case, the judge expressed the view that the employer’s duty of care extended beyond physical injury to ‘psychiatric damage’ and that the employer ‘has a duty to provide his employee with a reasonably safe system of work and to take reasonable steps to protect him from risks which are reasonably foreseeable’. Earnshaw and Cooper (2001) note that, under English law, employers cannot avoid liability due to the particular susceptibility of individuals, once they are aware of such susceptibility: ‘once employers are put on notice that a given individual is susceptible to psychiatric harm, they will be liable if it is foreseeable in the circumstances that that individual will suffer such harm’ (Earnshaw and Cooper 2001: 47). A number of international bodies have recognised the potential harmful effects of stressful working environments, including the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Cox and Griffiths (1996) argue that organisations need to assess the risk posed by ‘psychosocial hazards’ as well as physical hazards. Psychosocial hazards are ‘those aspects of work design, and the organisation and management of work, and their social and organisational contexts, which have the potential for causing psychological or physical harm’ (Cox et al. 1993, 1995). Although much legislation governing health and safety requires risk assessment of the effects of physical hazards on health and safety outcomes, more recently attention has been focused on assessing the risk of psychosocial hazards on health outcomes (Cox et al. 1995; Cox and Griffiths 1996). In 1993 the European Framework Directive on Health and Safety at Work stated that the employer has ‘a duty to ensure the safety and health of workers in every aspect related to the work’, although a minority of European countries have special legislation relating to psychosocial hazards.

Despite the increased awareness of the potentially harmful effects of occupational stress and psychosocial hazards, the focus has been largely directed at physical and psychological health and well-being. There has been little emphasis on the physical effects of psychosocial hazards, in terms of work-related accidents and occupational injuries. Although there is an assumption within many models of stress that frequent and/or severe accidents are a behavioural outcome of stressful working conditions, there is little explicit discussion of the relationship between occupational stress and work-related accidents. When the full range of negative implications are considered both in terms of ill-health and occupational injuries, the business costs associated with occupational stress are extremely high.

Costs associated with occupational stress

Employees are increasing aware of the impact that occupational stress is having on their work, health and well-being. The International Social Survey Program, conducted in fifteen OECD countries, found that 80 per cent of employees report being stressed at work (OECD 1999). The UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) estimates that 20 per cent of employees admit to taking time off work because of work-related stress and 8 per cent consult their general practitioner on stress-related problems (Earnshaw and Cooper 2001). A survey on working conditions by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions showed that 57 per cent of European workers consider their health is negatively affected by work and 28 per cent felt that their health and safety was at risk (Paoli 1997). Occupational or workplace stress accounts for a high proportion of sickness absence. The HSE estimates that 60 per cent of all work absences are caused by stress-related illnesses, totalling 40 million working days per year (Earnshaw and Cooper 2001). Schabracq et al. (1996) estimate that about half of all work absences are stress-related. The costs associated with sickness absence are high, for example, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) estimates that in financial terms, sickness absence costs some £11 billion per year in the United Kingdom, of which it has been estimated that about 40 per cent is due to workplace stress. This amounts to approximately 2–3 per cent of gross national product (GNP), or £438 per employee per year (CBI 2000).

It is estimated that occupational stress is involved in 60–80 per cent of accidents at work (Sutherland and Cooper 1991). When work accidents and injuries are included, the costs associated with occupational stress escalate further. Although in the United States alone, 65,000 people die each year from work-related injuries and illnesses (Herbert and Landrigan 2000), work-related fatalities are relatively rare, compared to the numbers of employees injured at work, who subsequently take sickness absence. Dupre (2000) estimated that in approximately 50 per cent of work accidents that occurred in Europe (in 1996) absence from work ranged between two weeks and three months. In Australia the average absence for compensated injuries was two months in the period 1998–9 (National Occupational Health and Safety Commission 2000). It is estimated that 80 million working days were lost in the United States due to workplace accidents in 1998 (US Bureau of the Census 2000). Work accidents are damaging not only for those involved, but also for their employers. Work injuries cost Americans $131.2 billion in 2000, a figure that exceeds the combined profits of the top 13 Fortune 500 companies (National Safety Council 2001). In the United Kingdom, it has been estimated that work accidents cost employers £3–7 billion per year, equivalent to approximately 4–8 per cent of all UK industrial and commercial companies’ gross trading profits (Health and Safety Executive 1999).

This brief overview indicates the enormity of the costs associated with stress-related illness and accidents, and highlights the potential benefits of successfully managing the risks of occupational stress. There are often hidden business costs that are incurred as a result of work-related illness and injuries, including the costs of training and recruitment of temporary cover for absent employees.

The nature of occupational stress

Contemporary definitions of stress tend to favour a transactional perspective; this emphasises that stress is located neither in the person nor in the environment, but in the relationship between the two (Cooper et al. 2001). Within this perspective the term ‘stress’ refers to the overall transactional process, not to specific elements, such as the individual or the environment. Stress arises when the demands of a particular encounter are appraised by the individual as about to exceed the available resources and, therefore, threaten well-being, and necessitate a change in individual functioning to restore the imbalance (Lazarus 1991). Stressors refer to the events that are encountered by individuals, while strain refers to the individual’s psychological, physical and behavioural responses to stressors (Beehr 1998).

Stressors

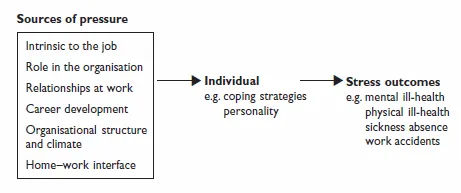

Sources of occupational stress were categorised by Cooper and Marshall (1976) as intrinsic to the job; role in the organisation; relationships at work; career development; organisational structure and climate; home–work interface (see Figure 1.1). These broad categories have been supported by later research, including Cox (1993) and Cartwright and Cooper (1997). Those that are ‘intrinsic to the job’ will include physical aspects of the working environment, such as noise and lighting, and psychosocial aspects, such as workload, and will vary in importance depending on the job, e.g. health care professionals experience high workload, the need to work long hours, time pressures and inadequate free time (e.g. Wolfgang 1988; Sutherland and Cooper 1990); while money- handling and the threat of violence at work are stressors for bus drivers (Duffy and McGoldrick 1990). Sources of pressure are derived not only from factors inherent in the job itself, but also from the organisational context, such as the structure and climate of the organisation (e.g. management style, level of consultation, communication and politics). Research shows that organisational stressors can have more impact, even in seemingly ‘stressful’ jobs, than factors intrinsic to the job, e.g. the police (Hart et al. 1995) and teaching occupations (Hart 1994). Hart et al. (1995) found that hassles associated with police organisations (e.g. communication, administration) were the main predictor of psychological distress among police officers.

Figure 1.1 The occupational stress model.

Source: adapted from Cooper and Marshall (1976).

Sparks and Cooper (1999) emphasise the need to measure a broad range of stressors, in order to reflect specific situations. A number of empirical studies have found that job-specific stressors are important in predicting outcomes for particular occupations (e.g. anaesthetists; Cooper et al. 1999), and that generic stressors vary between occupational groups (Sparks and Cooper 1999). Furthermore, significant differences have been found between work groups and departments within organisations, reflecting perceptions of different subcultures (Cooper and Bramwell 1992).

Sparks et al. (2001) identify four sources of stress of particular importance, due to the changing nature of the modern business world: job insecurity, work hours, control at work and managerial style. Recent trends in working practices across Europe have witnessed an increase in work pace (Paoli 1997) and the emergence of alternative work schedules, with some workers completing work shifts in excess of eight hours (Rosa 1995), while others work compressed schedules so that a working week of 36–48 hours is completed in three or four days (Sparks et al. 2001). In Europe, it is an increasingly common practice to base work schedules on weekly, monthly or yearly work hours (Brewster et al. 1996). Although EU legislation on working hours (European Commission Working Time Directive 1990) has resulted in a slight decline in annual work hours, in other countries, particularly where labour markets have been deregulated (e.g. United Kingdom, United States, New Zealand) work hours have increased (Bosch 1999). The OECD (1999) survey found that 35 per cent of UK employees work more than 40 hours per week. A meta-analytic review of the literature found significant relationships between long work hours and employees’ mental and physical ill-health (Sparks et al. 1997).

Cooper (1999) notes that the psychological contract between employer and employee is being undermined to the extent that employees increasingly no longer regard their work as secure. A European survey (International Survey Research (ISR) 1995) conducted across 400 companies, located in seventeen different countries, revealed that employment security declined significantly between 1985 and 1995. This trend is reflected in employee perceptions of job insecurity, which are having serious effects on health and well-being in European workers (Borg et al. 2000; Domenighetti et al. 2000). North American employees are experiencing similar effects, for example, McDonough (2000) found that, for Canadian workers, perceived job insecurity was significantly associated with reduced general health and increased psychological distress.

Role of individual factors

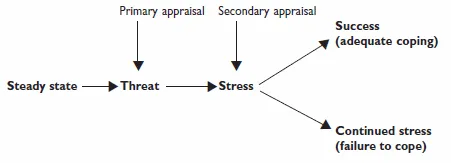

Occupational stress has been defined by many researchers (e.g. Cox 1978; Cummings and Cooper 1979; Quick and Quick 1984) as ‘a negatively perceived quality which as a result of inadequate coping with sources of stress, has negative mental and physical health consequences’. There are two key dimensions of this definition: in order for an individual to experience stress symptoms, first, the source of stress must be ‘negatively perceived’, and second, the individual must display ‘inadequate coping’ (see Figure 1.2).

The experience of stress symptoms is therefore both subjective and dependent on individual differences. If a source of stress is positively perceived, e.g. as a challenge to be overcome, then the individual will not experience negative outcomes. However, some individuals are predisposed to perceive themselves in a negative light, that is, they are high in ‘negative affectivity’ (Watson and Clark 1984), and are, therefore, more likely to perceive job situations as stressful. Research studies have found that individuals high in negative affectivity (NA) are more likely to report stress symptoms (Spector and O’Connell 1994; Moyle 1995; Cassar and Tattersall 1998). Parkes (1990) suggests that NA has a moderating influence on the stress–strain relationship, making high NA individuals more vulnerable to perceived stress, a hypothesis that has found empirical support (Moyle 1995; Cassar and Tattersall 1998). Research has suggested that workers with particular personality traits are more vulnerable to stress: a more ‘external’ locus of control (Spector 1986; Newton and Keenan 1990; Rees and Cooper 1992) and Type A behaviour pattern (Newton and Keenan 1990). Other personal characteristics, such as age and sex, may also affect vulnerability to stress (Jenkins 1991).

Figure 1.2 The Cooper–Cummings framework model.

Source: adapted from Cartwright and Cooper (1997).

Stressors do not act on a passive individual; he or she is likely to take action to cope with sources of pressure. It is when these coping strategies fail that an individual will experience negative stress outcomes, such as physical or mental ill-health. Proactive, task- focused coping styles, which deal with the problem itself (e.g. improving time management skills to cope with a heavy workload) are likely to be more effective than reactive, emotion-focused coping styles, which aim to mitigate the side-effects (e.g. smoking or drinking alcohol to reduce feelings of anxiety or depression). Koeske et al. (1993) differentiate between two types of coping: control coping (e.g. ‘took things a day at a time, one step at a time’; ‘considered several alternatives for handling the problem’; ‘tried to find out more about the problem’) and avoidance coping (e.g. ‘avoided being with people in general’; ‘kept feelings to myself’; ‘drinking more’). In a longitudinal study looking at newly appointed case managers (dealing with challenging patients), they found that control coping had a significant buffering effect over time against the negative consequences of stress; the exclusive use of avoidance coping strategies, in the place of control coping, had detrimental effects. The coping strategies that individuals adopt will depend on a variety of factors including personality, experience and training, for example, Koeske et al. (1993) found that avoidant copers tended to demonstrate a more external locus of control (LOC). Hurrell and Murphy (1991) argue that individuals with an internal LOC suffer from fewer stress symptoms, as they are more likely to define stressors as controllable and take proactive steps to cope with them; however, in ...