1

Introduction

Vogliamo un mondo fatto per la gente,

di cui ciascuno possa dire “È mio”!

dove sia bello lavorare e far l’amore,

dove il morire sia volonta di Dio.

“25 aprile 1945”

Tragic, backward, hopeless, downtrodden, static, passive: such adjectives dominate scholarly literature on the Italian peasantry (see app. A for definition) even to the present day. Although there is some truth in all these words, they fail to capture the self-image and world view of rural Italians. Vigorously and occasionally successfully, the Italian peasantry responded to a bewildering variety of innovations over the past two centuries. Many of these innovations, linked to what all too casually is called modernization, were imposed from without; the impetus for other changes, however, came from within villages, towns, and hamlets. In these rural communities individuals and, more often, families applied time-tested values in an effort to make sense of the volatile realities of life. Villagers made no sharp distinction between traditional and modern; rather, like Dilsey, they endured. And if alterations of their surroundings were largely beyond their control, had it not always been that way?

Four words capture the essence of the Italian peasant’s response to life: fortuna, onore, famiglia, and campanilismo. Because so much of the past was beyond human understanding, because the present was uncontrollable, and because the future was unpredictable except for those with magical powers, fatalism (fortuna) dominated the peasantry’s world view. When a southern Italian contadino remarked that “fatalism is our religion; the church just supplies the pageantry of life,” he used the word “fatalism” in two different senses. The concept of fate as preordination or cosmic determination emerges at all levels of speculation on what the species is about, and judged in terms of theological debate on God and man, peasant attitudes may be characterized as poorly articulated and gloriously ambivalent. Only partially related to fate as predestination is the concept of fatalism as a “generalized sense of powerlessness” and a major dimension of alienation. Indeed, for most students of modernization (and its students all too easily become its advocates), fatalism is the bete noire that explains resistance to change or, in the view of a recent scholar working with data on Latin America, that allows post hoc rationalization of individual and societal failure.

My own use of the term “fatalism” to describe in part the world view of Italy’s peasantry involves neither philosophical questions of predestination nor value judgments about responses to change. Rather, I refer to the sum total of all explanations for outcomes perceived to be beyond human control. Fatalism begins with the mysteries of God, Mary, and the saints, but it goes well beyond Roman Catholic doctrine. It explains why one man is a day laborer and another a shoemaker or a landowner. It accounts for outbreaks of typhoid fever and malaria, crop failures, abundant rainfall, the success of immigrants to America or Argentina, and even the refusal of aged and burdensome parents to die. Confronted with the assertion that becoming a shoemaker is a matter of individual effort and the control of malaria a result of improved knowledge of disease transmission, the peasant nods wisely and readily concedes that fate works in myriad ways.

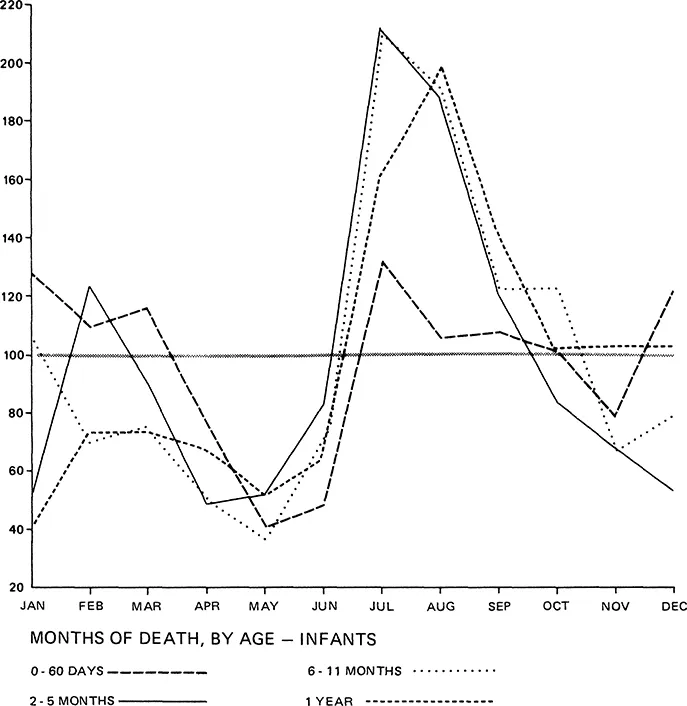

Above all, the persistence of fatalism in rural Italy until virtually our own time, especially in southern Italy (the Mezzogiorno), reflected an accurate assessment of that society’s inability to control or even to explain life and death. The clustering of deaths in seasonal cycles, and of births and marriages as well, gave a structural rhythm to life. But this pattern, regular for the village as a whole, encompassed a series of uncontrollable events for the individual and the family. Only with the conquest of unpredictable death, until “passing away” became something that happened mostly to old people who had lived their full measure of time, did contadini act as if they might usefully and knowingly measure and plan the future.

Onore (honor, respect, dignity) has meaning only within the context of fortuna and famiglia. Fate determines how much hunger a family suffers, how many of its infants and children die, whether its efforts will result in good situations for its marriageable members. But the villager does not sit idly by to await the uncontrollable outcome of fate. For every happening some response is required, and it is the pattern of such responses that establishes onore. The shame suffered by the Sicilian family whose unmarried daughter becomes pregnant is no mere cinema cliche. The loss of onore, which extends even to the girl’s second cousins, arises not from fate but from a human failing—their families did not properly chaperone the young couple—and therefore it can be rectified by family action: the children must marry. Villagers will snicker and attribute the weakness to a vague genetic failing, but the onore of both families is nonetheless restored. The struggle to maintain onore in the area of sexual behavior may make excellent cinema script, but it is only a small part of the total effort required. Respect and dignity come with continued support of one’s immediate family at a level appropriate to one’s station in life. For women especially, respectability means devout attendance at mass without becoming a bizzocca (house nun); it means strictly observing mourning customs, accepting fully the request to be a godparent, and, above all, responding to the sudden needs of the extended family.

La famiglia is at the center of Italian life; it is not only a convenient way to provide for the proper raising of children but also the society’s basic mode of organization. The individual without family is anomic; groups larger than la famiglia are secondary. In politics, in work, in the economy, in religion, in love, indeed in all of life, perceptions exist and decisions are made primarily in terms of family. In a political struggle the well-organized family sees to it that it has members in the opposing factions. Thus, when the outcome is determined, at least one member will be on the winning side and in a position to shield other members from possible retaliation. Although not always worked out in a cold and calculated manner, this system aided many families in the bitter partisan struggle in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Campanilismo, the unity of everyone who lives within the sound of the village church bell, is secondary only to family in the code of rural Italy. In some cases campanilismo involves specific and highly valued rights—for example, to the allocation of firewood from communal forests or to the gathering of mushrooms, chestnuts, and berries. In most cases, however, communal landholding gave way centuries ago to private plots, and village unity rests upon less tangible factors. Nonetheless, and despite the increasing intrusion of regional and even national government in education, public safety, road building and the like, loyalty to place of birth remains strong. Often this loyalty is expressed in sharply negative characterizations of nearby places. The natives of a Sicilian village describe five surrounding towns as, respectively, (1) struck by evil spirits, (2) mentally backward, (3) filled with cuckolds, (4) perfumed, and (5) a haven for gangsters. Campanilismo finds positive expression in high rates of marriage between local boys and girls and in the tendency of immigrants in distant lands to establish enclaves restricted to fellow villagers or townsmen.

Together these four values served to define the peasant’s self-identity and to circumscribe his behavior. The transition from peasant to rural proletarian, I shall attempt to demonstrate, involved transformations in each of these values. Spatial self-identity (campanilismo, Gemeinschaft) gave way to class and to national perception (irredentismo, Gesellschaft). Action taken in terms of family came into conflict with individualism. Interpersonal relations became defined less by honor and reciprocal obligation than by legal codes and cash transfers. Fatalism yielded to anthropomorphism. Fate, honor, family, and village are more than cultural codes but less than universal psychological realities. The chapters that follow trace the impact of demographic change upon rural Italian culture primarily, though not exclusively, through these four values.

In the introduction to his recent fine study, A History of Italian Fertility during the Last Two Centuries, Massimo Livi-Bacci expressed a deeply felt need “to link the results of demographic analysis with the pace and patterns of the cultural modifications in the Italian society. Unfortunately,” he continued, “we have done little more than acknowledge a need for a higher level of knowledge in this field.” I hope that the present study contributes to fulfilling precisely this need. Because the main focus is on culture, there are some organizational decisions about the following chapters that may confuse or even dismay historical demographers. Findings on natality, nuptiality, and mortality are not grouped as such. Instead, they appear arrayed in various chapters according to the cultural question under consideration. For example, data on mortality appear as part of an analysis of changing perceptions of time and again in a chapter on work. Perhaps the index will help.

Nor is the organization strictly chronological and periodized from 1800 to 1970. Rather, I have tried to capture at least partially the rural view of history, of what has happened in the Italian countryside over the past two centuries. This history, then, begins with the immutable, with matters perceived to be beyond human control: wind, rain, soil, and stones. The following chapter, “Past,” forgoes a full narrative history of each of the four communities under intense study in order to concentrate on peasant perceptions of the past as a determinant of the present and future. Chapter 4 presents the basic demographic data and links these to seasonal agricultural rhythms of time. Beginning with the chapter on family and continuing with the one on work, the main focus is on human institutions perceived as mutable and even as agencies of change but that for the most part have functioned in quite the reverse way. The next two chapters, on space and on migration, deal with behavior which peasants view as fundamentally initiative, controllable, and of their own doing. The final chapter finds the future in the past.

Before proceeding to the study proper, some readers may wish to know a bit more about the research base upon which it rests. Thus far I have made no reference to regional, climatic, and cultural distinctions. Italy is a highly varied land, as are its people; I hope to give this variety due attention by distinguishing developments in different regions. Specifically, my analysis deals with four villages or rural towns: Albareto in Emilia-Romagna, Castel San Giorgio in Campania, Rogliano in Calabria, and Nissoria in Sicily (see fig. 1). These four communities in no sense constitute a random sample of all Italy, and several interesting regions are excluded entirely. Reasons for my choices are made clear in the acknowledgments; in essence, I took what I could get. The problem, then, is the relationship between these four villages and “rural Italy” or the Italian peasantry.

Fig. 1.

Italy: locations of Albareto, Castel San Giorgio, Nissoria, and Rogliano

Would that I could beg the question by dismissing “rural Italy” as a stylistic shorthand to avoid repeating four hard-to-remember names. (One of my students had the good sense to dissuade me from using the computer-processing acronym that still haunts me—NARC.) No, when I write “rural Italy” I mean to state a conclusion based on primary research on four communities and not contradicted (unless otherwise noted) by the preponderance of scholarly work on other parts of rural Italy. I do, with many historians and a fairly strong consensus of anthropologists, believe further that rural Italian culture, at least to the line of the olive trees, should be viewed as Mediterranean. Albareto is north of this line and serves throughout this study as a reminder of the complexity of the Italian versus Mediterranean distinction. Of course the conclusions are tentative, set forth within a paradigm not because that paradigm is proven or even provable but in order to make sense of things. Four villages are only a start; the fifth, sixth, and nth are to be welcomed.

Finally, a note is in order concerning levels of evidence. Although I do not share fully the notion of a “hierarchy of reliability” set forth by those distinguished cliometricians Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, there are varying kinds of evidence in the chapters that follow. Often, seemingly stronger evidence exists on less interesting or consequential points and vice versa. For example, data on age at first marriage are abundant and highly reliable; findings from one community may be compared against another and changes over time may be traced and studied. Thanks to Livi-Bacci’s work, it is relatively easy to place local findings—how “typical” they are—within the national scene. Calculation of standard tests of statistical significance is straightforward, although interpretation is made problematic since the communities do not constitute random samples. Nonetheless, I am confident about the accuracy of the age at first marriage data graphed herein. But there are more tantalizing questions: what impact did changing marital ages have on modes of choosing a spouse, on familial relationships, parental authority, household economy, and conception control? Statistical findings often show what is to be explained or yield perimeters of what is possible, results that are useful but limited. Wherever it has seemed appropriate, I have gone beyond numerical findings and asked questions for which the evidence is literary, oral, or visual. Local proverbs, several familial stories passed through four generations, and a government report on declining parental authority support, but hardly constitute certain proof for, my contention that rising female nuptial ages reflected a shift from familial to individual marital choice. Partly as a matter of style, but more importantly because I reject the idea that historical evidence is strictly hierarchical, findings based on non-statistical material are not relegated to the subjunctive, the conditional, or the ubiquitous “perhaps.” No one recognizes better than an author just how tentative many conclusions must be.

More than a decade ago a scholar writing about the Italian South asked, “How Would You Like to be a Peasant?” Such rhetorical questions, sympathetic though their intention may be, reflect a limitation in many academic approaches to understanding the peasantry. A peasant is born, not trained, elected, or chosen. Not until the last generation or two was it possible for more than a few peasants to decide successfully to become something else. Only the nostalgic arrogance of weekend farmers and the well-intentioned bungling of developmental planners are served by acting as if nonpeasants might be what thay are not and as if peasants ought not to be what they are. The question for peasants was not contentment but survival, not self-fulfillment but familial obligation, not advancement but stability. Within admittedly narrow constraints, however, peasants struggled to master their world or at least to function within it. Antonio Gramsci’s wry comment in his ninth prison notebook captures well one essence of peasant history.

Prima tutti volevano essere aratori della storia, avere le parti attive, ognuno avere una parte attiva. Nessuno voleva essere “concio” della storia. Ma può ararsi senza prima ingrassare la terra? Dunque ci deve essere Taratore e il “concio.” Astrattamente tutti lo ammettevano. Ma praticamente? “Concio” per “concio” tanto valeva tirarsi indietro, rientrare nel buio, nell’indistinto. Qualcosa è cambiato, perchè c’è chi si adatta “filosoficamente” ad essere concio, chi sa di doverlo essere, e si adatta.

My study, then, concerns not the ploughmen of history but its fertilizer.