![]()

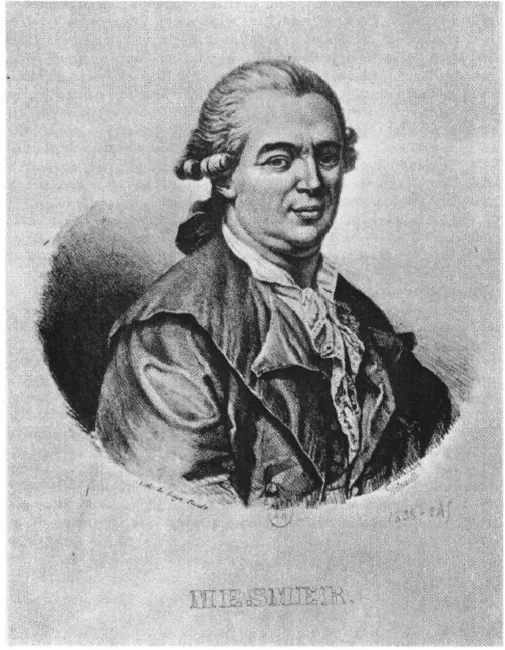

Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–7815). Although always a controversial figure, modern hypnosis began with him and his disciples, who called it animal magnetism. From the collection in the Institute for History of Medicine, Vienna. Copy courtesy of Henri F. Ellenberger.

PART I. Pain and Hypnosis

| Chapter 1. | Hypnosis |

| Chapter 2. | Pain |

| Chapter 3. | Controlling Pain |

| Chapter 4. | Hypnosis in Pain Control |

The scientific foundations upon which the understanding of hypnosis is based have become much firmer in the last two decades. In the course of research, much has been learned about the effectiveness of hypnotic procedures in the alleviation of pain.

To keep all in perspective, the account begins with an orientation to hypnosis, and then turns to pain—knowledge about it and theories to explain it. The more usual methods of controlling pain—drugs, surgery, physical medicine, and psychological procedures—are reviewed. The evidence for hypnotic relief of pain is then examined, in the light of experimental evidence gathered under well-developed methods of control and measurement.

![]()

1 Hypnosis

It is possible to discuss the relationship between hypnosis and pain with confidence because of the advances in the understanding of hypnosis that have occurred in the last two decades. With the establishment of research laboratories working continuously on problems of hypnosis, and of professional societies composed of those interested in a scientific basis for its clinical use, hypnosis must now be considered as a serious topic in psychology and in the healing arts.

Hypnotic-like behavior has been reported from the dawn of history, and such behavior can be observed today in the rites of cultures little influenced by modern civilization. The early origins are shrouded in mystery and magic; for our purposes we may begin two centuries ago, with Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), an Austrian physician who came to prominence in Paris. His form of hypnosis under the name of animal magnetism was important enough to be known as mesmerism (with a small m), a name still heard occasionally as a synonym for hypnosis.

Disparaging remarks have been made about Mesmer because of the dramatic manner in which he conducted his therapeutic sessions in Paris in the late 1700s. The patients sat around a baquet—a tub filled with water and iron filings—holding onto iron rods through which the magnetic influence might reach their bodies. The master himself would appear in his elegant silk robe, assisting in the transfer to the patients of the marvelous animal magnetism exuding from him. The patients would eventually go into convulsions, and would then be taken to a recovery room where they became normal again, hopefully rid of their complaints. A committee of inquiry was set up in 1784 by the King of France, composed of leading scientists of the day, including Benjamin Franklin, ambassador from the young United States. Using good experimental designs, the committee showed that the “magnetic” influence could be transferred as well by wooden rods as by iron bars, and that the influence upon the patient, although present, was a result of the imagination. Hence Mesmer was discredited, although his methods and theories lived on.

Mesmer was obviously wrong in his theory, but two things may be said in his defense. In the first place, he was attempting to use modern physical science to replace some of the superstition of his day. It may be remembered that this was the Age of Enlightenment in France, the time when Diderot's famous Encyclopedia was appearing. Second, even though the results were produced by imagination, they were indeed being produced; we shall note later how important imagination has become in the interpretation of hypnosis.

The first point—that he was trying to use modern science, even if he did not use it well—can be documented by a controversy he had with Father Johann Joseph Gassner (1717-1799) an exorcist of the time. Father Gassner was a Catholic priest in a small village in Switzerland; through the Church's practices of exorcism, he got rid of “the Evil One” and cured himself of headaches, dizziness, and other disturbances that had been troubling him. He then began to exorcise others within his parish, and by 1774, patients began to come to him from miles around. He soon received invitations to practice elsewhere. There was much opposition to Gassner, for many of those participating in the enlightenment wished to be rid of practices that they considered irrational. The Prince-Elector Max Joseph of Bavaria appointed a commission of inquiry in 1775 and invited Mesmer to show, if he could, that the results of exorcism could be obtained as well by “naturalistic” methods. Mesmer was able to produce the same effects that Gassner had produced—causing convulsions to occur and then curing them. He declared that Gassner was an honest man, but that he was curing his patients by animal magnetism without being aware of it. Mesmer won the day, and Gassner was sent off as a priest to a small community. Pope Pius VI ordered his own investigation, from which he concluded that exorcism was to be performed with discretion.

Mesmer was not prepared to consider the role of imagination, the explanation which the Royal Commission had proposed, because psychology was not then far enough advanced for imagination to be taken seriously in relation to science. However, despite a temporary setback, mesmerism spread to other parts of the world. Among its adherents in the United States, one to be remembered is Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866), who cured a bedridden invalid later to become famous as Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), the founder of Christian Science.

Undaunted by scientific objections to their explanations, later mesmerists were impressed by the results they could achieve, most dramatically in relieving pain in major surgery. An English surgeon, John Elliotson (1791–1868), reported in 1834 on numerous surgical operations performed painlessly under mesmeric sleep; in 1846 a Scottish doctor, James Esdaile (1808–1859), reported on 345 major operations performed in India with mesmerism as the sole anesthetic. General chemical anesthetics were not yet in use; ether was introduced in 1846, chloroform in 1847. The opposition to surgery under mesmerism was intense, and the practice died out rapidly after the chemical anesthetics became available.

Hypnosis was rescued from oblivion by another English physician, James Braid (ca. 1795–1860), who wrote in the 1840s. Braid divorced himself from the mesmerists, relating hypnosis to “nervous sleep;” he eventually gave it the modern name of “hypnotism.” He never broke with the medical profession and was a far less controversial figure than Elliotson. In some sense, hypnosis as we know it began with Braid, who used it widely in his medical practice, even treating his own pains with self-hypnosis.

Despite the moderation of Braid's views, hypnosis declined again until another revival occurred in France. Here we find two schools of thought in disagreement about hypnosis—that of the Salpêtrière, headed by Jean-Martin Charcot (1835–1893), and the Nancy school, led by Auguste Ambrose Liébeault (1823–1904) and Hippolyte Bernheim (1840–1919). From them we are led to Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), a name more familiar today.

Charcot was the most distinguished neurologist of his day; the fact that he gave demonstrations of hypnotic phenomena in his clinic and explained hypnosis neurologically gave it scientific respectability. Charcot presented his findings on hypnosis in a paper read in 1882 before the French Academy of Sciences—the same academy that had assisted in the earlier rejection of mesmerism. Charcot believed that hypnosis was essentially hysterical and that its major manifestations were limited to those who suffered some abnormality of the nervous system. He was wrong in this, but because he linked hypnosis to disease, his findings became acceptable to his scientific colleagues. Freud spent some time with Charcot in 1885–1886, while Charcot emained interested in hypnosis. The Nancy school, on the other hand, regarded hypnosis as an entirely normal phenomenon and attributed it to the influence of suggestion. History has proven the Nancy school more nearly correct. Freud wished to learn from both sides and, in fact, translated the works of both Charcot and Bernheim into his native German.

Because both Charcot and Bernheim were medical men of sound reputation, their disputes were considered as part of normal scientific discussion; hypnosis now became a matter of scientific interest and investigation. This interest was soon so general that the First International Congress for Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnotism was held in Paris in 1889. The list of participants includes many distinguished names, such as the American psychologist William James, the Italian psychiatrist and criminologist Lombroso, and the psychiatrist Freud, who did not establish psychoanalysis until later.

At this peak of interest in hypnosis in the 1880s, academic psychologists took their places along with the clinicians. It was most natural for William James, in 1890, to include a chapter on hypnotism in his classic Principles of Psychology; Wilhelm Wundt, often called the father of modern experimental psychology, wrote a book on hypnotism; Wilhelm Preyer, important in the history of child development, had his book also; and there were many others in many languages. Several journals devoted to hypnosis appeared, and long bibliographies were assembled to help keep abreast of the flood of books and articles. By 1900, however, it was almost all over.

In Vienna, Freud, along with Joseph Breuer (1842–1925), had begun to use hypnosis successfully in psychotherapy with patients then classified as hysterical. The result was their classic book, Studies in Hysteria, published in 1895. By the time the book appeared, however, Freud had rejected hypnosis. He had already substituted his method of free association and psychoanalysis; only the couch remained from his hypnotic practice. This was another blow to hypnosis, for because of their psychological orientation, Freud's followers might have been sympathetic to the use of hypnosis had not a kind of taboo been set up against it.

Pierre Janet (1859–1947) was Charcot's successor, although too independent to be thought of as a disciple. He had a large share in developing the theory of dissociation of personality as an aspect of hypnosis, and had followers in the United States early in this century—particularly Morton Prince (1854–1919), founder of the Psychological Clinic at Harvard. Janet lived a long life and was aware of the fluctuations of interest in hypnosis. In one of his books, published in English in 1925, he remarked that hypnosis was quite dead—until it would come to life again.

The new life for hypnosis began at the end of World War I. Treatment of soldiers with “shell shock” from trench warfare by English psychologist William McDougall (1871–1944) and others brought hypnosis to the attention of scientists. An important milestone in the experimental study of hypnosis was reached when Clark Hull (1884–1952) began experimentation as a professor at the University of Wisconsin, and later at Yale University. Hull published a classic book on Hypnosis and Suggestibility in 1933. This work, meticulous in its use of scientific controls and statistical tests, stands even today as a model for scientific method as applied to hypnotic phenomena. Unfortunately Hull, like Freud, abandoned hypnosis once he had worked successfully with it; few of his students followed up this interest, despite his listing more than one hundred studies that needed doing but that he had not gotten around to. But enough work was done that when Weitzenhoffer reviewed the experimental literature twenty years later, he could cite 508 references, many of them, of course, preceding the date of Hull's book.

A resurgence of interest followed World War II and the Korean War. Psychiatry was more advanced by this time than it had been in World War I; many psychiatrists found advantages in hypnotherapy, in part because it could achieve results more quickly than the methods of psychotherapy in which they had been trained. Dentists, too, found that they were able to use hypnosis when their normal supplies of local anesthetics might not be available. Clinical psychologists, drawn into service, also found hypnosis useful. After the war years, societies related to clinical and experimental hypnosis were established, with journals to publish research findings and case material. Specialty boards were established so patients could be directed to hypnotic practitioners with adequate credentials. Both the British Medical Association and the American Medical Association passed resolutions stating that training in hypnosis might appropriately be given in medical schools. Research laboratories were established at some leading universities, with support from government agencies and private foundations. Hypnosis was now on firmer ground and could advance without the sharp fluctuations of interest that had occurred in the past.

We are now prepared to consider the knowledge about hypnosis that has accumulated through the research efforts of recent decades, following this awakened interest.

Hypnotic Responsiveness

It has long been known that, quite apart from the skill of the hypnotist, people differ in the degree to which they are responsive to hypnosis. Records kept on nearly 20,000 cases by various investigators in the nineteenth century showed that roughly 10 percent of the subjects were refractory or essentially nonsusceptible to hypnosis; about 30 percent reached only a drowsy-light state; another 30 percent reached a moderate state; and the rest reached a deep state, often called “somnambulistic” by analogy with sleep-walking. The figures differed widely from one investigator to another, however, because there were no standard measurements. Intensive efforts in recent years have been devoted to producing better tests of hypnotic responsiveness, and then to finding personality characteristics related to scores on these tests. As with nearly all human measurements, subjects would be expected to vary in their responsiveness from one end of the scale to the other, with more people achieving intermediate scores.

The construction of a hypnotic responsiveness scale is logically very simple. The person to be studied is first given a brief standard induction of hypnosis, of the kind that long experience has shown makes a person feel hypnotized if he is responsive to these induction procedures. Two favorite methods of induction are the eye closure method and the hand levitation method. In the eye closure method, the subject stares at a small target, such as a tack on the wall, while the hypnotist suggests relaxation, drowsiness, and eventually, eye-closure. The intent is that the subject should hold his eyes open as long as possible and have the feeling of involuntary action as the eyes “close of themselves.” Once the subject's eyes are closed, the assumption is that he has become lightly hypnotized; further suggestions are given to make the involvement in hypnosis more profound. When the hand levitation method is employed, the subject is told to concentrate on a hand in his lap. He is then instructed to note that the hand is getting light and is beginning to lift, to move up toward his face. The subject becomes relaxed, his eyes close, and, when his hand touches his face, he is comfortably hypnotized and the hand descends slowly to his lap. There are many variations, but if a standardized test is desired, the suggestions follow a standard pattern and are given in a uniform manner.

Following such a routine induction, the subject's hypnotic responsiveness is tested by giving him suggestions to which hypnotized persons are known to respond. For example, the subject may be told to hold his arms out in front of him at shoulder height, with his hands about a foot apart, palms facing inward. Placing the hands in this position is merely a cooperative response, made as well by the less hypnotizable as by those more highly hypnotizable. Next the subject is given the suggestion that his hands are moving together involuntarily, as though an external force were acting upon them. For many people, the hands begin to move together; then they report that it does indeed feel as if the hands are being attracted toward each other, or being pushed together. If the hands move some specified amount—say to within 6 inches of each other—that item is “passed” as an indication of responsiveness. In a standardization test with college students, 70 percent passed this item, making it an “easy” item. Others are much harder. In one such item, the subject is told to place the palms of his hands together and to interlock his fingers. He is then given the suggestion that the hands will be so tightly locked together that he will be unable to open them when he is told to do so. He is then told, “Try to open your hands. Go ahead and try.” Only one-third of the students tested in a standardization sample were unable to open their hands in the 10 seconds allowed—half as many as had their hands move together in the easier item above. By collecting together a dozen such tests of hypnotic responsiveness and observing varied performances, a larger sample of hypnotic responsiveness may be obtained. Age regression (return to childhood); hallucinating something not present; performing an act at a signal when out of hypnosis (posthypnotic suggestion); forgetting what was done in hypnosis until a release signal is given (posthypnotic amnesia)—these represent other kinds of performance that may be called for....