- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Attitudes and Psychophysical Measurement

About this book

Published in 1982, Social Attitudes and Psychophysical Measurement is a valuable contribution to the field of Cognitive Psychology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Attitudes and Psychophysical Measurement by B. Wegener in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Experimental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| I | APPROACHES TO SUBJECTIVE MAGNITUDE |

| 1 | Psychophysical Measurement: Procedures, Tasks, Scales |

Lawrence E. Marks

John B. Pierce Foundation Laboratory

and

Yale University

1. INTRODUCTION

Having been asked to review psychophysical scaling procedures, I take the task quite literally, by which I mean to review certain basic topics, that is, to view them again—to take another look at them with the hope that examining them from a new perspective perhaps will give new insight into some of the complicated issues and perplexing problems that continue to beset psychophysics. Reviewing can mean taking a very fresh look; it can even mean reconsidering premises that previously may have seemed obvious. What I want to review are those methods that call upon people to make quantitative or quasi-quantitative judgments about their subjective states (about sensations, perception, attitudes, or whatever). By and large, these methods are magnitude estimation and magnitude production on the one hand, and various types of rating (numerical, adjectival, graphic) on the other.

The Enterprise of Scaling

The modern enterprise that Fechner may be said to have begun is the quantification of mental events. Interested as I always am in historical precedents, I pass along to you a passage in the Republic (IX, 587), where Plato (1961, p. 815) engages in a bit of psychological quantification. As Plato reports it, Socrates computes the relative happiness of king and tyrant, the result being that the king—the just king, that is—is said to be 729 times as happy as the tyrant (ratio of 36:1). Whether one wants to consider this as an antecedent or precursor to the method of ratio estimation is debatable, but surely it is an early attempt to quantify what we would call psychological values.

The use of mathematical symbolism to represent sensations or other internal, psychological events—the quantification of sensation that goes by the name psychophysical measurement—is really a most congenial part and parcel of the more general enterprise of science, much of which makes use of mathematics as a model, or, if you will, as a kind of metaphor. But it is interesting to note that the type of psychophysical measurement that forms much of the subject matter of this conference doubles or maybe even squares this metaphor; for when the subject matter of a science consists of “quantitative judgments” made by people, the metaphor is carried one step farther. When we study such judgments, we are examining people’s metaphorical behavior, and when we quantify sensation by quantifying quantitative judgments, we are constructing metaphors for metaphors. It is good to keep in mind that many, maybe most, such quantitative judgments are metaphorical extensions through language or other symbolic systems, these systems being the media and sometimes the messages of many of our metaphors. In a sense, comparing the validity, reliability, or whatever other properties of different scaling methods is much like saying: “What are the good metaphors?”

If posing the question this way—in terms of “good metaphors”—makes one uneasy, perhaps this malaise will be relieved by considering that the criterion for “good” is, in some opinions anyway, largely pragmatic. Good metaphors are useful metaphors. Good psychophysical scales are useful psychophysical scales—scales that play a useful role in laws and theories of behavior. I do not think this is a very controversial point of view. It probably has the distinct advantage of being virtually tautological and, despite Plato or Keats, surely more defensible for application to the realm of science than other potential criteria for “good” such as simplicity or beauty. (Which is not to say that many a scientist’s Weltanschauung does not rest on the latter criteria. See Marks, 1978c, especially chaps. 5 and 6.)

It’s time to get into the real business. The remainder of this paper is divided into two major parts. In the first part, I give an overview of magnitude and rating procedures, pointing out in particular some of the problems and difficulties that befall their use and beset the interpretation of their results. In the last part of the paper, I present some new data in a context that, I hope, persuades you to review some of the old controversies.

2. PSYCHOPHYSICAL SCALING METHODS

Magnitude and Rating Procedures

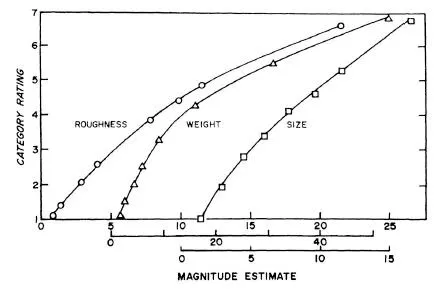

Let me introduce here what is one of the main issues considered in this paper— the relationship between results obtained with magnitude procedures and with rating procedures. In certain respects, the methods of magnitude estimation and category rating do not appear so very different. They both ask subjects to try to assign numbers to psychological values. This makes it all the more puzzling why the two methods so often yield systematically different results—the well-known concave downward curve when ratings are plotted against the corresponding magnitude estimates. A few examples appear in Fig. 1.1.

What I would like to suggest is that, when these procedures do yield such a discrepancy, the discrepancy results from the two methods inducing the subjects to interpret the two tasks in (psychologically) different ways, with the consequence that the relative psychological values of the sensory/perceptual elements can differ. To those of us who have found the disagreement between rating scales and magnitude scales puzzling, one reason that we find it so is because we have made, implicitly at least, an assumption about converging operations—that in an ideal system the operations that define magnitude estimation and category rating will converge, nay should converge, on a single psychophysical function. Although sometimes they do—in some studies with continua like pitch, apparent position, length—more often they do not, especially with continua like loudness, brightness, weight, and size.

As an aside, let me mention that not everyone seems to find the relation a puzzle (Eisler, 1963, 1978). In fact, the experimental results that Eisler reported in 1963 are particularly instructive in this regard. He obtained magnitude estimates and category ratings of apparent length, which showed the systematic nonlinearity between them: The magnitude estimates were nearly proportional to physical length, whereas the category ratings were negatively accelerated functions of length. (As I just indicated, ratings and estimates of length are often collinear, as in the study by S. S. Stevens & Guirao, 1963, but not in this case.)

FIG. 1.1 Category ratings (seven-point scale) of roughness of sandpapers, heaviness of weights, and size of circles, plotted against the corresponding magnitude estimates given to the identical stimuli. The same 12 subjects performed both tasks on all three continua. Data from Marks and Cain (1972).

FIG. 1.2 Lines with relative physical lengths of 1, 6, 86, and 91 units.

Consider for a moment what subjects might be doing when they judge lengths of, say, 1, 6, 86, and 91 physical units (Fig. 1.2). When the method is magnitude estimation, the subjects give numbers approximately in the proportions of 1, 6, 86, and 91. But, when the method is rating on a 10-point scale on which 1 is defined by a 1-unit line and 10 by 91-unit line, a 6-unit line is often put in category 2, whereas an 86-unit line is often put in category 10. Thus, the magnitude estimates suggest that the differences between psychological values of 1 and 6 units and between 86 and 91 units are equal, whereas the ratings suggest they are not. My synthesis of this antinomy is as follows: I would suggest that, yes, the two psychological differences are unequal, as the ratings suggest, but also that the two differences between the pairs of psychological magnitudes are equal, as the magnitude estimates suggest.

Perhaps this statement itself is puzzling, so let me expand. Pairs of stimuli, such as lengths, can form a perceptual relationship that is readily identified as a psychological interval or difference. The pair 1–6 has a different value on this psychological scale than has the pair 86–91, and this difference expresses itself in the unequal spacing on the category scale. The perceptual relation on which the pairs differ is a psychological interval, but a psychological interval is not necessarily equal to a linear difference between psychological magnitudes. Some relevant data appear later.

Problems with the Methods of Psychophysics

Let me start off with a review of some of the features—both the good and the bad features—of magnitude and rating procedures. And if I seem to emphasize the latter at the expense of the former, it may be partly because, in actuality, the bad often seem to be intrinsically so much more appealing than the good (Satan after all is by far the most interesting character in Milton’s Paradise Lost) and also because there are problems with all methods of psychophysics, and these problems must be taken seriously and dealt with at some point.

Every method has advantages and disadvantages of various sorts. With magnitude estimation and magnitude production, there is a basic uncertainty (variation) in the range of the responses, e.g., in the range of numbers assigned when the procedure is estimation, in the range of stimulus settings when the procedure is production. Such uncertainty generally cannot occur with rating procedures because the ranges of both stimuli and responses are set by the experimenter. But rating procedures have their own kind of uncertainty (variation), which manifests itself in the distribution of responses to stimuli within the (fixed) ranges.

Estimation Versus Production. It is well-known that procedures of magnitude estimation and magnitude production tend to give results that differ systematically. S. S. Stevens and Greenbaum (1966) argued that subjects show a general tendency to contract the range of whatever variable they control. This compressing of range expresses itself, for example, in the expon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- INTRODUCTION:

- PART I: APPROACHES TO SUBJECTIVE MAGNITUDE

- PART II: PSYCHOPHYSICAL MEASUREMENT IN SOCIAL APPLICATION

- PART III: DIFFERENCES AND RATIOS IN SENSORY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOPHYSICS

- Author Index

- Subject Index