- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Imperialism and Resistance

About this book

A unique critique of the new economic and military imperialism of the United States and its allies in the twenty-first century.

Inspired by the anti-globalization and anti-war movements, in which the author himself has played a crucial role, this is also an accessible introduction to the huge changes in global politics since the dominance of the American Empire with the end of the Cold War. It covers the key areas of:

- the nature of the new imperialism

- the economic power of the US

- globalization and inequality

- wars in the post Cold War era

- oil and empire

- resisting the new imperialism.

This lively, provocative and practical book is an essential guide to the politics of the new world order, which also offers constructive suggestions on how the global resistance movement should develop. It is important new reading for activists, students and all those wanting to understand and challenge the new imperialism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imperialism and Resistance by John Rees in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

International Relations1 Arms and America

The shock to the international state system caused by the collapse of the Eastern bloc in 1989 is a root cause of the instability now endemic in global politics. The bi-polar architecture of the Cold War world fixed all power relations in their place from the Second World War until the East European revolutions. The US is now attempting to create a new imperial order, but the process is contested and dangerous.

This is a seismic shift in the landscape of world politics. If we were to reach for historical parallels then only the rise of European colonialism up to the First World War or the fall of the Iron Curtain across Europe after the Second World War would be appropriate in scale and consequence. To fully grasp this enormity a review of Cold War imperial rivalry is necessary.

The Cold War

The United States emerged from the Second World War as the only major power whose civilian economy had grown at the same time as its military economy. In every other combatant nation, Allied or Axis, the civilian economy had been ravaged for the sake of waging war. The US penetration of the global market advanced at the cost of enemies and allies alike everywhere from the Far East to the European heartlands of capitalism. As direct European colonial administration gave way to the wave of national liberation struggles and the emergence of independent states in the Third World, so US-led military alliances, client states and economic domination replaced them in many parts of the globe.

The exception, and it was a huge exception, was in Russia itself and those areas of Eastern Europe where the Nazis had been driven out by force of Russian arms. At Yalta and subsequent conferences this military reality became an agreed division of Europe by the major powers. After the 1949 revolution China also fell beyond the direct reach of the western military and western corporations.

For the entirety of the Cold War period the kind of struggle between the major powers that had given the 20th century two world wars was transformed into a different kind of battle for superiority. In the first instance the superpowers battled it out in hot wars in every corner of the Third World. From South-East Asia, through Africa and Cuba, all the way to Chile every battle was fought under the banners of West and East, Capitalism and Communism.

The main form of direct conflict between the US and Russian superpowers was the arms race. The arms race was not only about the sheer military might of the contending armed forces. It was about economic muscle. In a nuclear arms race, in an arms race that was also a space race, in a race where weapons superiority means technological superiority, the scale and sophistication of the contending economies was the decisive factor.

A rough military parity between the superpowers emerged that would deter either side from beginning a conventional war in Europe. However there was never an economic parity. Russia industrialised later and its economy was always smaller than that of the United States. The Russian and some of the Eastern European economies were for a considerable period faster growing than most of their western competitors. State control insulated them from the vagaries of the world market and allowed them to concentrate resources on building or rebuilding their industrial strength. Over the longer term, however, the reconstruction of the world market and the pressure of the arms race undermined the viability of the state dominated economies in Eastern Europe.

By the time Ronald Reagan embarked on the Star Wars project in the 1980s the explicit goal was as much to exert economic pressure on Russia as it was to develop a weapon the Russians could not match. The economic resources expended in research and manufacture were as important as the efficacy of the weapons produced.

The arms race also took its toll on the US economy. The cost of winning the arms race was borne overwhelmingly by the US, but the benefits were felt not just by the US but by all those western economies who participated in the long post-war economic boom underpinned by arms spending. At the height of the Reagan arms boom the US was spending 7 percent of GNP on the military but the other NATO countries were spending half that figure.1 This kind of disparity, which existed throughout the Cold War, meant that German and Japanese capital, for instance, grew in the world market at the expense of the US.

Moreover, as the size of the world economy grew so the scale of arms spending necessary to underpin the boom grew as well. The US was reaching the limit of what it could afford to spend on arms not just relative to its competitors but also relative to the total amount needed to sustain global growth. These fissures in the world system were apparent from the 1970s when global growth rates began to fall to half what they had been at the height of the post-war boom. From this moment on boom and bust cycles assumed greater severity than at any time in the post-war years.

By the end of the Cold War the US had economically undermined the East European economic structure by means of the arms race, but the scale of arms spending needed to do this had also eroded its own economic advantage over its western rivals.

At the start of the 21st century the US certainly remains the most powerful economy in the world but it no longer so exceeds its rivals that it can determine the course of events by the use of its economic weight, as it did through the Marshall Plan at the end of the Second World War. Multilateral economic institutions like the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO, enjoy US support in a way that their political and military counterparts no longer do. This is not because the US is somehow more naturally collaborative in the economic field but simply because the relative decline of the US economy obliges it to be so.

There is no similar decline in the relative power of the US military. In fact, quite the reverse: US military power emerged from the Cold War more overwhelmingly dominant on a global scale than it has ever been.

It is in this contradictory couplet–relative economic decline and absolute military superiority–that much of the meaning of US strategy in the 21st century is to be found.

The United States and the post-Cold War world

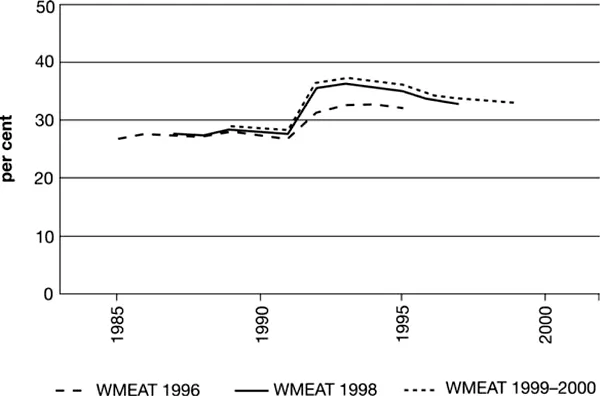

The end of the Cold War was supposed to herald a new world order of peace and prosperity. The rationale for high arms expenditure, the nuclear stand-off between the superpowers, was over. Indeed there was a fall in the proportion of national wealth devoted to arms spending.

The global proportion of Gross National Product (GNP) spent on arms declined from 5.2 percent in 1985 to 2.8 percent in 1995. Over the same decade the percentage of GNP spent by the US on arms fell from 6.1 percent to 3.8 percent. In the same years NATO countries cut arms spending from 3.5 percent to 2.4 percent. In Britain the figure fell from 5.1 percent to 3 percent.2 But the fall in the percentage of GNP spent on arms is not the whole story.

The fall in US arms spending was not as sharp as in other states. So the proportion of US spending as a total of all nations’ arms expenditure rose dramatically at the end of the Cold War.

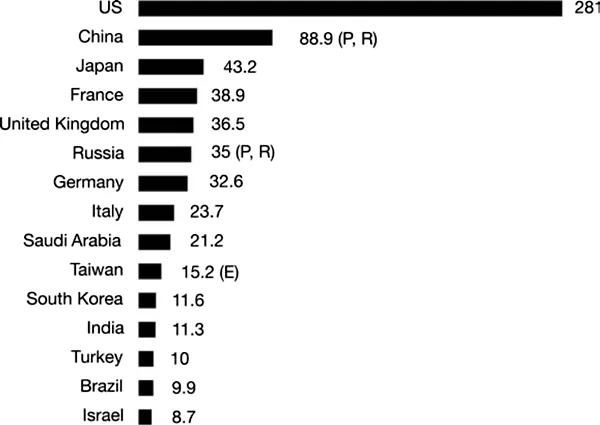

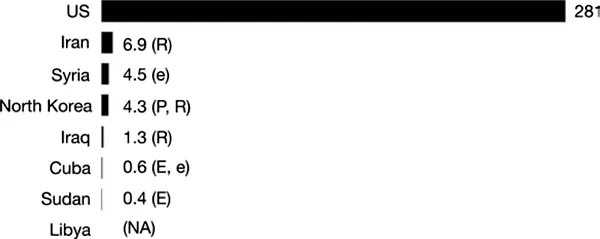

The result was a massive shift in the military balance of power in favour of the United States. Nowhere was this shift more decisive than in the relationship between the US and the so-called ‘threat states’.

The general shift in the military balance can be seen inTable 1.1, again highlighting the especially dramatic advantage that the US now enjoys over the ‘threat states’.

Figure 1.1 US military spending as a percentage of world military spending, 1985–19993

Figure 1.2 Top 15 nations, as ranked by military spending in billions of US dollars in 1999.4

(E): Estimate based on partial or uncertain data; (P): Value data converted from national currency at estimated purchasing power

(E): Estimate based on partial or uncertain data; (P): Value data converted from national currency at estimated purchasing power

Figure 1.3 US and some potential enemy nations, as ranked by military spending in billions of US dollars in 1999.5 (e): Major share of total military expenditures believed omitted, probably including most expenditures on arms procurement; (E): Estimate based on partial or uncertain data; (NA): Data not available; (P): Value data converted from national currency at estimated purchasing power parity; (R): Rough estimate

The study from which Table 1.1 is drawn concludes ‘Despite post-Cold War spending reductions, the United States and its friends and allies today have a spending edge over potential adversaries that is far greater than existed during the Cold War’.6 Moreover, ‘the burden of defense borne by the United States, its allies, and close friends is today more equitably distributed among the members of this group–even though the United States continues to devote more of its GNP to defense than is the average for the group.’

As the full reality of this situation emerged during the 1990s sections of the US ruling class began to formulate a strategy adequate to the new balance of power. This was no incidental matter. It was clear to US policy makers that they possessed overwhelming military might. Clear too that the collapse of the East European bloc meant that a third of the globe that had been closed to western corporations and military strategists since the Second World War was now, literally, open for business. However, it was by no means clear how to go about exploiting this situation nor was it clear how dangerous, both internationally and domestically, the new world order would be for US rulers.

Table 1.1 US military spending as a fraction of spending by selected groups of states, 1986 and 1994

The first Gulf War in 1991, for instance, demonstrated the power of US arms–but it also revealed that those directing US foreign policy were keen to stress multilateralism, including the involvement of the United Nations. Indeed, the US entered the first Gulf War on a programme very much borrowed from the Cold War. The US air-land battle plan was drawn from existing NATO strategy in Europe. The US had long realised that it would face a Warsaw Pact army in Europe that outnumbered NATO forces. In order to compensate for this imbalance it had developed the idea of carpet-bombing the rear echelons of the enemy, destroying reserves, cutting off the front line troops and disrupting supplies.

A similar plan already existed to meet a Russian thrust into Iran, should one materialize. Norman Schwarzkopf, the US commander in the Gulf War, simply took this strategy over for use against the Iraqi army. But in the transition there were some important alterations in plan and circumstance. Firstly, the air-war component was massively enlarged until it became the largest and most devastating air assault ever conducted. The US flew 88,000 sorties against Iraq in six weeks. They dropped more munitions in that time than were dropped on Germany in the whole of the Second World War.7

Secondly, the targets were not the rear of the army of another superpower, but the cities of a third world country. Stephen Pelletiere, the CIA’s senior political analyst during the Iran-Iraq war concludes: ‘In the Iraqi case, the strategy was massaged, so to speak, by the air-war theorists… into a strategy of bombing the Iraqi homefront into submission… the Americans took a style of war meant to be used against the army of a fellow superpower (Russia) and turned it against a third-rate power, shifting the focus to the Iraqis’ homefront.’8

Similarly, the ideological justifications for war in 1991 and throughout the rest of the decade presented an incoherent admixture of elements drawn from the Cold War world and the post-Cold War world. Already in 1991 Saddam Hussein was a ‘new Hitler’, just as Nasser had been in 1956. In the United States’ Latin American adventures the ‘war against drugs’ emerged as a contender for the role of the leading ideological justification for war. The ‘war on terror’ was periodically in use as well. Before the attack on the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 none of these notions had the general ideological force that anti-communism had provided during the Cold War.

Indeed, the major difference between the Gulf War and the Cold War era lay not on the side of the United States but on the side of Iraq. It may or may not be the case that Saddam believed he had the acquiescence of the United States for the attack on Kuwait. But what he knew for certain was that there was no longer a Russian veto on his actions in the way that there would have been throughout the Cold War period. The Cold War bi-polar world held ‘rogue states’ in check by agreement between the superpowers. Now that dangerous stability was gone. The US fought the first Gulf War because it wanted no post-Cold War challenges to its power. This was immediately true in the Middle East but in the wider frame the US wanted the war to send a message to European and other ruling classes that it was still the world’s effective policeman. Ever since the rulers of the United States have been grappling with the question of how to contain future challenges to its power, hence its obsession with rogue states.

So through the first attack on Iraq and long before the attack on the twin towers the neo-conservatives in the American foreign policy elite were formulating a strategy for the US in the post-Cold War world.

The roots of US strategy

Henry Kissinger surveyed the post-Cold War world from the point of view of the US ruling elite and came to this conclusion: ‘Geopolitically, America is an island off the shores of the large landmass of Eurasia, whose resources and population far exceed those of the United States. The domination by a single power of either of Eurasia’s two principal spheres–Europe or Asia–remains a good definition of strategic danger for America, Cold War or no Cold War. For such a grouping would have the capacity to outstrip America economically and, in the end, militarily’.9

Increasingly throughout the 1990s voices were raised within the US establishment that argued for the US to find a way of dominating the ‘Eurasian landmass’. The right of the US foreign policy establishment had immediately recognized that the Middle East was strategically, economically, ideologically, not to mention geographically, at the heart of the Eurasian problem. Although ‘getting Eurasia right’ might not resolve all the US’s problems in other important parts of the world like Latin America or South-East Asia it was, nevertheless, disproportionately important. The first Gulf War was fought to demonstrate that no matter what else might be changing in the midst of the turbulent events of recent years in Eastern Europe and Russia, there was to be no change in US domination of the Middle East.

The first Gulf War had all but destroyed Saddam Hussein’s regime. Indeed it took the active connivance of the US, encouraging and then deserting a popular Iraqi insurrection in favour of the devil they knew, to keep Saddam in power. The subsequent UN sanctions regime, as we now know beyond all doubt, not only inflicted untold misery on the Iraqi people but also kept the Iraqi regime from developing any effective weapons of mass destruction. In a way the first Gulf War was won too well for the good of the US. Stephen Pelletiere explains: ‘With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the great threat to the Gulf (which allegedly the Russians had posed) was no more. Further, Iraq had been defeated… and even before that–in the Iran-Iraq War–Baghdad had succeeded in laying low the Iranians. So, effectively, there was no threat to the Gulf any longer and consequently no reason for the Americans to keep up a military presence there.’10

Yet the first Gulf War became increasingly regarded as a failure because it did not advance the cause which Henry Kissinger espoused, wider domination of the Eurasian landmass. For Washington hawks the first Gulf War was too ‘multilateral’ and too limited in its consequences both in Iraq and in the rest of the Middle East. In short, it was over too soon–a fact for which the hawks never forgave Colin Powell, the then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who had halted the pursuit of the retreating Iraqi army after the massacre on the Basra road for fear it would inflame anti-war opinion in the US.

The hawks’ wider aims and the narrower compelling goal of continued domination of the Middle East came closer together in the years of the Clinton presidency. The evolution of this policy was part of a wider shift in the Clinton administration’s foreign policy profile led by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and her mentor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Polish born Brzezinski is a central figure in the American foreign policy elite and to follow his career is to see the evolution of a central strand in US policy. Brzezinski was Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor and he had considerable influence on the first Clinton administration through his ally and Clinton’s National Security Advisor Anthony Lake. Brzezinski was an early advocate of NATO expansion and through Lake, was instrumental in getting Clinton to commit himself to this course as early as 1994. Brzezinski’s influence continued in Clinton’s second administration when his former pupil at Columbia University, Madeleine Albright, was made Secretary of State. Albright had also worked under Brzezinski in the Carter administration.11

Brzezinski’s ‘three grand imperatives of imperial geostrategy’ are ‘to prevent collusion and maintain security among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and to keep the barbarians from coming together’. And the most pressing task is to ‘consolidate and perpetuate the prevailing geopolitical pluralism on the map of Eurasia’ by ‘manoeuvre and manipulation in order to prevent the emergence of a hostile coalition that could eventually seek to challenge America’s primacy’. Those that must be divided and ruled are Germany, Russia and Iran as well as Japan and China.12 It was Brzezinski who infamously defended US suppor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Arms and America

- 2 US economic power in the age of globalisation

- 3 Oil and empire

- 4 Globalisation and inequality

- 5 Their democracy and ours

- 6 War and ideology

- 7 Resisting imperialism

- Notes

- Further reading