CHAPTER

1

The Hierarchy

Edward Tysons work and Charles Darwins work were the cornerstones of a new view of the place of the human species in the natural world. A nested hierarchy of creatures exists, and we are (progressively more exclusively) primates, anthropoids, catarrhines, and hominoids. The theory of evolution explains why that hierarchy exists, because more inclusive groups share more distant ancestors. Major conceptual revolutions occurred in parallel in 19th century biology (undermining anthropocentrism) and in 20th century anthropology (undermining ethnocentrism) in understanding our place in the world.

Introduction

Are humans unique?

This simple question, at the very heart of the hybrid field of biological anthropology, poses one of the falsest of dichotomies—with a stereotypical humanist answering in the affirmative and a stereotypical scientist answering in the negative.

Any zoologist is forced to concede that humans are unique in certain ways—that we are not apes, and are easily distinguished from apes, in the same way that ducks are not pigeons, and lions are not wolves. It is a possibly trivial sense—simply the observation that in the panoply of nature, our species is our species and not some other species—that implies at least a minimal amount of distinctness.

We are not unique in our fundamental biology, however. Our cells are almost indistinguishable from an ape’s cells—and as different from the cells of one ape species as that ape’s cells may be from those of another ape species. The components of our bodies, their functions and processes, are exceedingly similar to an ape’s. And one has only to watch a group of chimpanzees interacting to sense that their minds are like our minds.

Ape biology and human biology are of a piece with one another. And ultimately of a piece with clam biology and fly biology.

The study of human biology, however, is different from the study of the biology of other species. In the simplest terms, people’s lives and welfare may depend upon it, in a sense that they may not depend on the study of other scientific subjects. Where science is used to validate ideas—four out of five scientists preferring a brand of cigarettes or toothpaste—there is a tendency to accept the judgment as authoritative without asking the kinds of questions we might ask of other citizens’ pronouncements. Why, after all, would it matter what four out of five scientists prefer, unless there was some authority that came with that preference?

We can call this scientism: the acceptance of the authority of scientists. It is different from science, the process by which we come to understand and explain natural phenomena. The reason for this difference is simple. Science is the way in which we examine and confront the many things that might be true and prune them down to the few things that probably are true. It occurs by a process of “conjecture and refutation” (Karl Popper)1 or more euphoniously, “proposal and disposal” (Peter Meda war).2

The paradoxical flip-side to science is that the vast majority of ideas that most scientists have ever had have been wrong. They have been refuted; they have been disposed of. Further, at any point in time, most ideas proposed by most scientists will ultimately be refuted and disposed of. While this is fundamentally how our knowledge of the universe grows, it has the ultimate effect—and a threatening one—of impeaching the authority of scientists. Science, in other words, undermines scientism.

Nowhere is this paradox more evident than in the study of human biological variation. Scientists’ ideas are formed partly through what we like to imagine is the objective analysis of data; but also, like the ideas of anyone else, formed partly by their cultural upbringing and life experiences. The pronouncements of scientists on human variation may be as loaded with cultural prejudices as those of anyone else—and as history shows us, indeed they usually have been. Except that, as the pronouncements of scientists, these ultimately cultural values would subsequently be vested with the authority of science. The culture can consequently produce the values that the scientist validates, thus proving that the culture was right all along.

The study of biological variation in the human species is thus a bit different from other kinds of scientific endeavors. Biologists studying fruit-flies certainly have the same cultural prejudices of an era and class, yet it is generally difficult to imagine those cultural prejudices pervading their work. And it is more difficult to imagine those prejudices in their work as the basis of scientific authority to oppress or to degrade the lives of other people. The English mathematician G. H. Hardy described his attraction for his own field of scientific research: “This subject has no practical use: that is to say, it cannot be used for promoting directly the destruction of human life or for accentuating the present inequalities in the distribution of wealth.”3

Anthropology, on the other hand, can and has been used in precisely those ways. Anthropologists, consequently, are absorbed in their intellectual history—in learning from the mistakes of earlier generations of scholars. The more we understand those conceptual errors, which usually are visible only in hindsight, the more the science of the human species can grow—by the very process of proposal and disposal by which science functions.

This thesis forms the backbone of the present book. It is about the current state of our understanding of genetic diversity, its patterns and its significance, in our species. It is about the ideas that shape contemporary thought about human genetics. But the present was formed in the past; and to know where we are, it helps to know where we’ve been— for in some respects we are still there. One, after all, ignores intellectual history at one’s own peril. But in this case one ignores the intellectual history of human diversity not only at one’s own peril, but at the peril of many people.

Thus the sciences and the humanities fuse in the study of human biological diversity. The subjects are (on the one hand) data, and (on the other) the cultural history surrounding the collection and interpretation of those data. We try neither to exalt nor to profane the human species; we handle science in the same way. The human species is both different from, and similar to, other species; and science has been both useful and tragic in approaching these questions.

Pattern and Process

The relationship of humans to the natural world is a philosophical question of long standing. In the year 1699 it became an empirical question as well. In that year Edward Tyson, the leading anatomist in England, published the results of his dissection of a chimpanzee. Tyson had already written definitive monographs on the anatomy of a dolphin and an opossum, but the subject of the new monograph was different, for it bore directly upon the place of humans in the natural sphere.

The new monograph was called “Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: Or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie Compared with that of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man.” The specimen was neither an orang-utan nor a pygmy, but an infant male chimpanzee that had died of a jaw infection in England following a fall on board ship during the voyage from West Africa.

The creature proved to be immensely interesting, not least of all because reports of such beings from remote continents tended to confuse zoology, anthropology, and mythology. There were different kinds of animals in Asia and Africa, but there were also different kinds of people, and the reports of both were being spread by travelers with, like everyone, vivid imaginations. In fact, much of the confusion would not be sorted out for a century and a half; but Tyson managed to take the first steps in that direction.

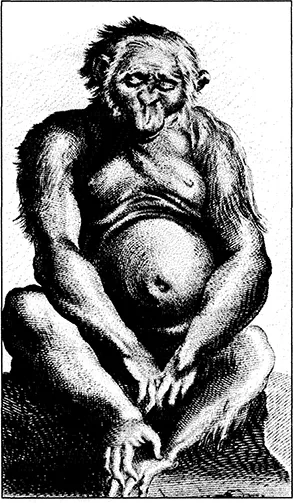

An ape had been described superficially by a Dutch anatomist named Nicolaas Tulp in 1641, but though he said he believed it came from Angola and had black hair, he nevertheless also called it an “Indian Satyr” and discussed what the natives of Borneo thought of it.4 Tulp’s account is not only highly mythological, but also unclear as to whether his subject was a chimpanzee or an orang-utan. His illustration is ambiguous (Figure 1.1). Nevertheless, Tulp named the animal following the local (Bornean) designation: orang-outang, or man of the woods [orang-outang, sive homo sylvestris].

Tyson was more secure about the origin of his subject, had seen it alive, had studied its body upon its death, and had devoted an entire monograph to it, not simply a few paragraphs in a medical text, as Tulp had done. As Tulp had reported, the animal indeed bore an extraordinary likeness to the human species.

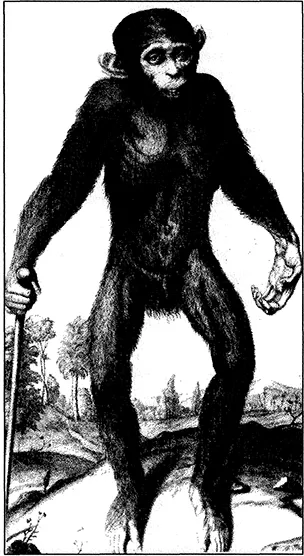

Tyson’s study showed him that there were 48 ways in which his “Pyg-mie” more closely resembled a human than a monkey, but only 34 ways in which it more resembled a monkey (Figure 1.2).5 According to Tyson’s biographer, Ashley Montagu, it represented the first scientific presentation “that a creature of the ape-kind was structurally more closely related to man than was any other known animal.”6

Figure 1.1 Tulp’s “Orangoutang” of 1641.

Monkeys had been known since antiquity: venerated by the Egyptians, dissected by the Greeks. Indeed, Vesalius in Renaissance Italy demonstrated that in certain ways the classical Greek anatomy of Galen was based on a monkey’s, rather than a human’s, body.7 Thus the similarity between human and monkey was well established, but there was certainly no doubt about the latter’s being a dumb brute, an animal. The “Pygmie,” on the other hand, was more ambiguous.

In spite of the extraordinary degree of similarity of organ, muscle, and bone to a person, the “Pygmie” nevertheless neither spoke nor walked. Tyson explained this paradox: the “Pygmie” didn’t speak since, possessing the physical faculties, it still lacked the mental ones (which proved, as Descartes had recently argued, that mind and body are separate entities). Further, it walked in the most curious way—on all fours, but with its weight born by the knuckles of the forelimb. This was so unnatural a posture, reasoned Tyson, that it must have been walking that way because of its illness, for it was clearly built for good old bipedalism.

Figure 1.2 Tyson’s “Pygmie” of 1699.

As any scientist does, Tyson used the mindset of his times to interpret his work, and that paradigm was the Great Chain of Being.8 In other words, the “Pygmie” formed a missing link that tied humans to other creatures physically, if not intellectually. The Great Chain of Being, which figures prominently in the study of humans, subsumed three related principles:9 first, that every species that could exist did exist; second, that every existing species could be organized along a single dimension, a line; and third, that every species on that line graded imperceptibly into the species above it and below it. Obviously different versions of this theory were adopted by individual scholars, but they all shared to some extent these postulates.10

The Great Chain of Being was a 17th-century interpretation of the pattern of nature, the organization one encounters upon examining the diverse forms of life. There was a parallel interpretation for how that pattern came to be, the process that generated it. The process was the instantaneous origin of each species, as is, at the beginning of history. Both the process and the pattern were miraculous, in that neither could be explained or understood by rational means. The creation and the Great Chain of Being could certainly be inferred, but how they happened or came to happen was neither known nor probably knowable.

Ultimately it was Linnaeus in the mid-18th century who overthrew the Great Chain of Being as the pattern of nature, replacing it with a “nested hierarchy”; and it was Charles Darwin in the mid-19th century who overthrew creationism with the process of “descent with modification.” The replacement of the older pattern and process with the newer, and its relation to the position of humans in the scheme of things, was arguably the major conceptual innovation of the 19th century.

The Pattern: Linnaeus

We attribute to Carl Linné (whose name was Latinized as Carolus Linnaeus) the initial perception of the pattern now recognized as absurdly conspicuous in nature. He is consequently hailed as the “father of sys-tematics” by virtue of his relationship to Mother Nature.

Linnaeus is often depicted as a classifier, forever insisting on giving names to species—which of course he did, but which others had done before him. His lasting contribution, however, lay in apprehending how those named entities fit together. In other words, he found structure at a fundamental level in the natural world, but it was a different structure from the one-dimensional ranking of the Great Chain of Being. Rather, Linnaeus...