- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Richard Wright's Native Son (1940) is one of the most violent and revolutionary works in the American canon. Controversial and compelling, its account of crime and racism remain the source of profound disagreement both within African-American culture and throughout the world.

This guide to Wright's provocative novel offers:

- an accessible introduction to the text and contexts of Native Son

- a critical history, surveying the many interpretations of the text from publication to the present

- a selection of reprinted critical essays on Native Son, by James Baldwin, Hazel Rowley, Antony Dawahare, Claire Eby and James Smethurst, providing a range of perspectives on the novel and extending the coverage of key critical approaches identified in the survey section

- a chronology to help place the novel in its historical context

- suggestions for further reading.

Part of the Routledge Guides to Literature series, this volume is essential reading for all those beginning detailed study of Native Son and seeking not only a guide to the novel, but a way through the wealth of contextual and critical material that surrounds Wright's text.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Texts and contexts

Richard Wright: a brief biography

At first, the young writer scarcely knew that he wanted to write, only that he wanted to read. But American racism – the white supremacist ideology that reached its nadir in the southern states that Wright called home – worked to frustrate even this modest ambition. Legislation enforcing a kind of apartheid throughout this region, among other things, did all it could to deny black southerners the right to an education (see Chronology, p. 47). State courts withheld money from black schools, prevented black pupils from entering the professions and even went so far as to ban black readers from municipal libraries. To those who were alert to such matters, however, this vicious legislation was itself built upon a paradox. Racist ideology publicly denigrated the intellectual capacity of African-Americans. But the effect of racist laws was ironically to acknowledge this capacity and to deny it the materials that it needed if it was to flourish. As the historian of the black South Leon F. Litwack has suggested:

Curtailing the educational opportunities of blacks, along with segregation and disfranchisement, were important mechanisms of racial control…. A story that would make the rounds among blacks…revealed …a marvelous insight into the workings of the white mind. As he was leaving the railroad depot with a northern visitor, a southern white man saw two Negroes, one asleep and the other reading a newspaper. He kicked the Negro reading a newspaper. ‘Would you please explain that?’ the Northerner asked. ‘I don’t understand it. I would think that if you were going to kick one you would kick the lazy one who’s sleeping.’ The white southerner replied, ‘That’s not the one we’re worried about.’1

Wright’s works would prove wonderfully alert to the paradoxes of such behaviour. More than any other American writer, he would expose the intellectual dishonesty of racism, showing that its small acts of intimidation and discrimination secretly acknowledged the potential for black equality that it officially

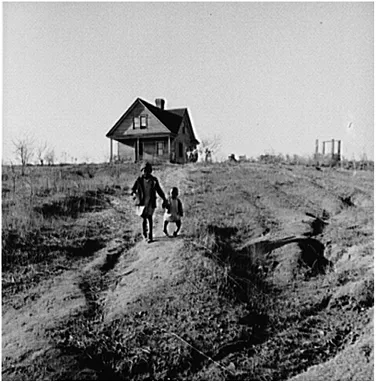

Figure 2 Negro children and old home on badly eroded land near Wadesboro, North Carolina. Photograph: Marion Post Wolcott, 1938.

denied. No other novelist is more alive to the vicious contradictions involved in racial segregation. And few others overcame quite so much discrimination, or had to be quite so courageous, in order to piece together a literary career. Indeed, we might ask ourselves: if white racists kicked other black men simply for reading newspapers, how on earth would they respond to the atheistic Marxist Richard Wright?

The circumstances of Wright’s youth were appalling. Born in 1908 near Natchez, Mississippi, Wright was the product of a southern culture not yet reconciled to Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Though abolished almost fifty years previously, slavery still cast a long shadow over this world. As Wright grew up on the same plantation on which his paternal grandparents had worked as chattel, memories of the so-called Peculiar Institution proliferated at home as well as in the worlds beyond it. Out there, the iconography of the Old Confederacy – the southern army defeated in the Civil War – dominated urban space. Statues of noble southern generals, frozen in the defence of slavery, stood outside courtrooms and political offices. Away from the towns, ‘lynching’ trees ripped into the limitless horizon of the Mississippi Delta. Everywhere stood the signs of Jim Crow segregation – legal signs such as ‘Whites Only’ and ‘For Colored Passengers’, and unofficial signs such as ‘Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You Here’ (see Chronology, p. 47).2

Named after a show in which a white minstrel ‘blacked’ up, this Jim Crow system that produced Wright was established after the American Civil War and the Reconstruction that followed it.3 More specifically, Jim Crow resulted from the fact that even those in the South who could accept slavery’s abolition felt inflamed by this subsequent Reconstruction. Reconstruction’s attempt to enfranchise former slaves and generally to secure them the rights of full citizens struck many white southerners as an act of gross humiliation. The fact that most of their white compatriots in the North shared their doubts about the wisdom of enfranchising ex-slaves effectively meant that Reconstruction never had much hope of succeeding. By 1877, the national government abandoned the enterprise altogether. In the historian Kenneth Stamp’s words, it renounced all responsibility for ‘the Negro, and, in effect, invited southern white men to formulate their own program of political, social, and economic readjustment’.4 Jim Crow segregation was what filled the void that this federal withdrawal left behind.

During the 1890s the national government’s indifference towards such segregation turned into active consent. Entering what the historian Hugh Brogan has called ‘its dimmest intellectual period’, the Supreme Court concocted ‘barely plausible constitutional arguments for upholding the racist legislation of the Southern states’.5 Most notoriously, its ruling on the provision of railway carriages in the Plessy vs. Ferguson lawsuit allowed southern states to provide ‘separate but equal’ facilities on the basis of colour difference. Segregation, from this point forward, was thus deemed constitutional.

Wright’s early years bore the brunt of racism’s new constitutional respectability. The understaffing and underfunding of the black schools that he attended as a boy directly resulted from the fact that, as the Supreme Court judges well knew, racist state legislators would always cherish the ‘separate’ part of the Plessy vs. Ferguson ruling precisely at the expense of its ‘equal’ element. While some of his individual teachers had good intentions, ultimately they could do little about the chronic disadvantages such schools faced. Leaving without any qualifications to speak of, Wright entered a world of menial and underpaid labour that was in many ways even more adept at keeping books beyond his reach. The merest whiff of intellectual curiosity invited ridicule from Wright’s employers and bemusement from his friends. Some whites felt that an African-American holding a book was fair game, a veritable provocation to racist attack. Others considered that such ‘uppity’ men or women should undergo some kind of debasement – should be sarcastically addressed as ‘Professor’ or ‘Doctor’, and generally put back in their place. To those black southerners willing to risk such treatment, moreover, the act of acquiring a book could itself be astonishingly dangerous. As his excellent autobiography of 1945 recalls, Wright was one of vast numbers of black southerners forbidden from using their local libraries thanks to Jim Crow bans. Indeed, in order to read H. L. Mencken (Mencken was a satirist from Baltimore, famous for lambasting southern vulgarity and for praising the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky among others), Wright had little choice but to break the law. As his autobiography would show, he had little choice but to address:

myself to forging a note. Now, what were the names of books written by H. L. Mencken? I did not know any of them. I finally wrote what I thought would be a foolproof note: Dear Madam: Will you please let this nigger boy – I used the word ‘nigger’ to make the librarian feel that I could not possibly be the author of the note – have some books by H. L. Mencken? I forged the white man’s name.

I entered the library as I had always done when on errands for whites, but I felt that I would somehow slip up and betray myself. I doffed my hat, stood a respectful distance from the desk, looked as unbookish as possible, and waited for the white patrons to be taken care of…The white librarian looked at me.

‘What do you want, boy?’6

This scene is pivotal to Wright’s autobiography. Prior to it, the life that Wright has written has been unrelenting in its difficulties. He has been abandoned by his illiterate father. He has watched helpless as his mother fell into ill health. He has been farmed out, separated from his brother Leon and forced to spend time in an ‘orphan home’ that feeds him with all the grudging contempt of a Dickensian institution. Jim Crow has, in other words, crept into every corner of his life. Even after Wright has escaped the orphanage and has gone to live in his grandmother’s house, it soon becomes evident that things will get no better for him. Hunger renews itself, colonizing his stomach as his grandmother forces him to subsist on ‘mush,’ beating him whenever possible for the crime of ‘talking at the table’.7

Books alone seem to offer the teenage Wright a way out. Stealing into the Memphis library, impersonating a white authority in print and a black servant in person, Wright’s defiance of the library ban seems to be the only way in which he can assert his humanity under Jim Crow law. Mencken’s importance consequently stands...

Table of contents

- Routledge Guides to Literature*

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes and references

- Introduction

- 1 Texts and contexts

- 2 Critical history

- 3 Critical readings

- 4 Further reading and Web resources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Richard Wright's Native Son by Andrew Warnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.