- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Help for Dyslexic Children

About this book

First Published in 2003. The authors' two earlier books, On Helping the Dyslexic Child and More Help for Dyslexic Children, are here presented as a single volume. This book is concerned with all aspects of helping dyslexic children. A brief account is given of what dyslexia is and what are the kinds of difficulties which these children have to face. A chapter entitled 'Help at home and at school' shows how they can be encouraged and given confidence; a chapter entitles 'Help for the seven-year old' indicates how informal help with reading and spelling can be given in the home; while further two chapters set out the essentials of a programme for teaching spelling which takes account of their distinctive strengths and weaknesses. Children are encouraged to build up their own dictionaries and sentences are include which will enable them to practise a systematic way what they have been taught. A final chapter makes some suggestions for help with arithmetic, and advise s given on the choice of the readers, workbooks and materials. The authors emphasise the need for common sense on the part of both parents and teachers, coupled with careful observation of the kinds of things which dyslexic children find difficult even when they display striking ability in other ways.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The aim of this book is a practical one, viz. that of making suggestions we hope will be of value to parents, teachers and others in providing dyslexic children with the help that they need. Theoretical issues have therefore been kept as far as possible in the background.

Since, however, there has been some degree of controversy (or, perhaps one should rather say misunderstanding and argument at cross purposes) about the existence and nature of dyslexia it may perhaps be of help if we indicate briefly the conclusions to which we have been led as a result of our experiences in the last twenty years.

During this time we have met many children who were clearly not just ‘slow’ or ‘stupid’ and who had had all the normal opportunities in school but who nevertheless showed quite striking difficulties in reading and spelling. One of the things which regularly emerged during assessments was that it was the same pattern of difficulties which kept recurring—a pattern which we shall describe in more detail in Chapter 2—and the accumulated evidence left us in no doubt that these regularities were something more than mere coincidence.

It was also clear that when the difficulties occurred they could not be attributed to poor teaching, to cussedness on the part of the child, or to inappropriate pressures on the part of the parents. The children whom we saw had received many different kinds of teaching; many of them, so far from being cussed, were desperately anxious to learn, and while we met many concerned and anxious parents it would have been arrogant for us to say that they were over-anxious or over-protective; and we found nothing to suggest that these parental attitudes were the main source of the children’s difficulties. Both from our own experience and from an examination of the literature it was plain that the difficulties often occurred in more than one member of the same family, and there was ample evidence that they occurred more often in boys than in girls, the ratio being about 3½ or 4 to 1.

These facts pointed inescapably to the conclusion that the difficulties were constitutional in origin; that is to say, there was something in the child’s physical make-up which prevented the normal acquisition of certain skills with words and other symbols. This view was further confirmed when we examined the literature on so-called ‘aphasic’ adults—those with disorders of thought and speech as a result of acquired brain injury: their mistakes, though varied, were in some ways very like the mistakes which we ourselves were meeting, for example a failure to put words and other symbols in the correct order in space and time. There was no good reason for supposing that more than a few of the children whom we met had undergone actual brain damage, but there was every reason to suspect some kind of failure of development or some kind of stunted growth which resulted in mistakes analogous to those made by brain-injured adults. The precise details of what causes dyslexia are not yet fully known, and indeed it is possible that the same pattern of difficulties may not always have the same cause; but that some kind of constitutional limitation is involved seems to us to be established beyond any reasonable doubt.

To describe a person as dyslexic, therefore, is to say that he displays a characteristic pattern of difficulties, with the implication that these difficulties are of constitutional origin.1

There has in fact been some rather fatuous argument as to the value of the term ‘dyslexia’, much of which, we suspect, is due to misunderstanding. If, as a parent, you are given conflicting advice on this point, we suggest that you rely on those who genuinely seem to you to understand your child’s difficulties. If you are a teacher we suggest that you try to find out more about these difficulties so as to ensure that the advice which you give is helpful and constructive. In our view the actual word ‘dyslexia’ is unimportant, since a word of approximately equivalent meaning would do as well, such as ‘specific learning disability’. What is important is the orientation— the particular view of the child’s difficulties—which use of the word implies.

It is sometimes said that parents and child are discouraged or demoralized when they are told that the child is dyslexic. In our experience this is almost never the case, at least if the word is properly explained to them. On the contrary they are often very much relieved. The reason seems to be that when one gives parents information about typical cases of dyslexia this makes sense of what would otherwise have seemed extremely bewildering. We have often met parents who could tell that something was wrong, without knowing what; and if one can make clear that the child is suffering from a recognized disability about which certain fairly probable predictions can be made, this makes it much easier for them to give the appropriate kind of support. Similarly, if teachers can be told, not, ‘Here is yet another backward reader,’ but, rather, ‘Here is a child with a disability which requires special understanding,’ it will be possible for them to help the child in a constructive way.

To sum up, there seem to us to be three main advantages in using the word ‘dyslexia’ (or some equivalent expression): it classifies, it explains, and it invites to action.

As far as classification is concerned, use of the word forces educationalists to distinguish those who are failing because they have a constitutional limitation from those who are failing because of lack of intelligence or opportunity; and it is disastrous in practice if this distinction is not noticed. As far as explanation is concerned, the fact that the difficulties are constitutional in origin calls for an adjustment of standards, since if a person is handicapped this is quite different from being ‘not very good’ at a particular task. Finally, if a person is dyslexic, it is important that something should be done for him; it is inexcusable in the light of present-day knowledge of teaching methods that any child in our educational system of average ability or above should be allowed to fail at reading and spelling simply because his problem has not been properly recognized.

Chapter 2

What to look for

If you suspect that your child is dyslexic, we suggest in the first place that you consult with his class teacher and, where appropriate, his head teacher. It may often be helpful if the child receives a complete assessment from an educational psychologist, and in that case we suggest that you ask for full details of the findings.

We strongly advise that you assume goodwill in the first place; and indeed there are reasonable grounds for optimism since understanding of dyslexia is far more widespread now than it was a few years ago. If, however, you have any reason to be dissatisfied with the treatment that your child is receiving or if his teachers do not appear to have understood the position when you yourself feel that there is something wrong, then even if you are reluctant to appear to be ‘making a fuss’ we strongly suggest that you do not let the matter rest there. You yourself have lived with your child over many years, and if you are dissatisfied our experience suggests that you may well be right. For suggestions as to where to go for help see p. 113

Moreover, even if there is some doubt about the diagnosis—as there may well be, for instance, in the case of a six- or seven-yearold —we have found that it is far wiser to assume that the child is dyslexic than to assume that he is not. Little is lost if one pays special attention to his reading and spelling at this age, and if the diagnosis is mistaken then his progress will be correspondingly more rapid. In contrast, if he is dyslexic but through high intelligence or other means has managed to ‘cover up’ so that his handicap is not fully apparent, the lack of early help is likely to be disastrous for him. It is also disastrous if well-meaning teachers attempt to reassure the parents of a dyslexic child by saying, ‘Don’t worry; he is a late developer and it will come’. We have seen far too many families who have been given this advice and after taking no action for several years have found that the hoped-for progress has not come. One needs to be very sure indeed, in our view, before deciding that a child is not dyslexic.

Perhaps the most important question that you should ask yourself is whether the child’s performance leaves you with a sense of incongruity. This can arise in particular if he is weak at reading and spelling (or, in some cases weak at spelling only) when in other respects he does not behave like a dullard at all. For example, he may be good orally and show high-level reasoning ability; he may have considerable electrical and mechanical skills; he may be outstandingly gifted at art or woodwork—yet when he tries to put his ideas down on paper he may fare far worse than many less gifted children.

It is of course important to use common sense and not jump to the conclusion that a child is dyslexic on too slender evidence. He may be failing at reading and spelling simply because he is not very bright, or perhaps because he has been absent from school. He may be suffering from the effects of some serious shock, for example a death or divorce in the family. In all these cases, however, one would expect a more generalized kind of failure, involving all school subjects, not the specific pattern of difficulties which one finds in dyslexia.

In practice the diagnosis is made as a result of the accumulation of a number of different signs, any one of which would be of no special significance on its own. The mistakes and confusions which we shall be describing in this chapter are mistakes and confusions which all of us make from time to time; it is simply that the dyslexic person makes more of them and makes them more frequently.

One of the most common signs is that the child shows persistent uncertainty as to which way round to place letters and figures, for example by misreading b for d or p for q or by making the corresponding mistakes in writing them. Thus a boy whom one of us taught misread boys as ‘dogs’, while among spelling errors we have met ‘tolq’ for tulip and ‘catqil’ for caterpillar. Sometimes the letters of a word are in the wrong order, for example ‘brian’ for brain. You should not, of course, take mistakes of this kind too seriously when they are made by fiveand six-year-olds; they are very common in the early stages of learning to read and write, and the great majority of children grow out of them by the age of seven or eight at the latest. In a dyslexic child, however, they sometimes persist well beyond this age. Also it can sometimes happen that although the mark which eventually appears on the page is the correct way round, say b and not d, earlier crossings out show that there was a large amount of uncertainty in the first place.

There is a complication in the case of spelling errors in that it is not always clear whether a particular error is a mistake over direction as such or whether the child is simply unsure—as a result of general confusion—what letter to put next. Thus if one finds ‘whte’ for with in a school exercise book one cannot tell whether the child is making a ‘back-to-front’ mistake over the th- or whether (as seems to us more likely) this is not a directional or ‘reversal’ error as such but is the result of guesswork and a vague feeling that the word should begin with wh.

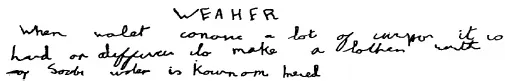

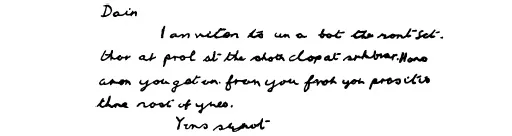

Often the spelling is very strange in appearance. Illustrations are given on pp. 8-9.

Both the examples on p. 8 were copied from school exercise books, and as neither of us was present at the time we do not know what either child was trying to say. On p. 9, however, are two further examples where, despite the oddity, it is possible to tell what was intended with some degree of confidence.

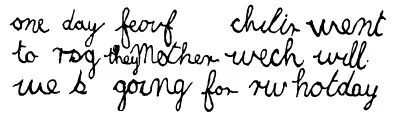

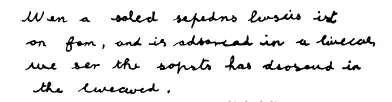

Although not all dyslexic children spell as strangely as this, these extreme examples are useful in that they exhibit in a particularly striking way the kinds of mistake which dyslexic children are likely to make. You will notice that an attempt is often made to use the sounds of the letters as a guide to spelling but that in the end-product many things seem to have gone wrong. For example, when ask in Sample 3 is spelled ‘rsg’ this suggests that the boy was confused between the name of the letter r and its sound; when he writes ‘feouf’ for five he is confusing f and v, presumably because their sound is similar. ‘Sepedns’ and ‘sopsts’ for substance in Sample 4 represent a similar confusion, this time between b and p. ‘On’ in Sample 4 would have been a plausible attempt at own but shows lack of familiarity with the -ow pattern which occurs in words such as low, mow, etc. ‘Soled’ for solid shows lack of awareness that -ed is a past tense ending and therefore inappropriate here. The inconsistent spellings of substance and liquid illustrate the difficulty, shown by many dyslexic persons, in remembering what they have written a moment earlier. Since these children were known to be intelligent in other ways their difficulty with spelling seems the more incongruous.

Sample 1

Sample 2

This kind of spelling is sometimes referred to as ‘bizarre’ spelling; and there is good reason for thinking that bizarre spelling and directional confusion regularly go together.

Here are some additional signs of dyslexia, though they do not occur in every case. Sometimes the handwriting is curiously awkward, as in the case of Sample 1. Sometimes the child is reported as being clumsy in his movements, and in some cases there is evidence of speech difficulties. A very large percentage are unable to learn arithmetical tables and many have difficulty with addition and subtraction, some of them finding it necessary to use their fingers or marks on paper and then carry out the operation one unit at a time. In many cases there is difficulty in reciting the months of the year and, among younger children, the days of the week. Some are late in learning to tell the time, and many have difficulty in remembering strings of numbers, for example telephone numbers. Some are unable to repeat longer words orally without getting the syllables in the wrong order, for example the words preliminary and statistical.

In brief, then, a dyslexic child is one who has (or has had) unusual difficulty with both reading and spelling, his performance being discrepant with what might be expected from his intellectual level. Often he muddles b and d at an age when other children no longer do so. His spelling is frequently bizarre in the sense described above, and at least some of the signs mentioned in the last paragraph will almost certainly be present in a way which cannot just be coincidence.

A concluding note. The use of standardized tests

If there is any doubt as to a child’s general ability or level of educational attainment, arrangements can be made for him to take standardized tests. In this context we are thinking in particular of intelligence tests and tests of reading and spelling. When a test has been standardized, this means that it has been given to a large number of children—probably thousands—and that figures are available which show what is the average or expected performance for children of a given age. On the basis of the results you can then tell how far a particular child is above or below the average.

Sample 3 One day five children went to ask their mother, Where shall we be going for our holiday?

Sample 4 When a solid substances loses its own form, and is absorbed in a liquid, we say the substance has dissolved in the liquid.

In the case of dyslexic children, however, various c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 What to Look for

- Chapter 3 Help at Home and at School

- Chapter 4 Help for the Seven-Year-Old

- Chapter 5 Building a Dictionary

- Chapter 6 Word-Endings and Word-Beginnings

- Chapter 7 Help with Arithmetic

- Appendix I A Sample Dictionary

- Appendix II Exercises

- Appendix III Supplementary Word-Lists

- Appendix IV Word-Lists for Chapter 6

- Readers, Workbooks, and Materials

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Where to Go for Help

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Help for Dyslexic Children by E. Miles,Mrs Elaine Miles,Professor T R Miles,T. R. Miles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.