Chapter One

In the Beginning

The span of time

The first human beings moved into Britain about 450,000 years ago, a length of time so remote that it is impossible for the average person to comprehend. Throughout the greater part of it, human progress was so slow that the same stone tool types were used with little change for hundredsof centuries, and social economy changed only as climatic and environmental conditions dictated. It might help the reader to suggest that if Christ had been born yesterday, the appearanceof the first people in Britain would have begun some seven and a half months before. On the same time scale all ensuing history from the arrival of the first farmers to the present day would have to be squeezed into the last three and a quarter days.

This vast span of time is best understood in geological terms. The Pleistocene period can be divided into a number of stages marked by changes of climate. These correspond to cold and warm phases referred to as glacials or interglacials but, in actuality, it would seem that the extremes of each (for example the presence of ice sheets or relatively warm parts of an interglacial such as the climate of the present day) only occupied a minor part of that time. For much of the middle and late Pleistocene period the climate would have been cooler than today in Britain. The cold stages are known as the Anglian, Wolstonian and Devensian, with the Hoxnian and Ipswichian warm stages in between them. Following the Devensian stage is the Flandrian warm period in which we live today. The Wolstonian stage was much longer than the others and spread over 250,000 years, but it was broken up by less cold periods called interstadials. In much the same way cold phases in the interglacials are known as stadials.

During the extremes of glacial periods great sheets of ice spread from the Arctic south to the British Isles causing a world-wide drop in sea level of up to 100 m. (109 yd), due to the water stored in the ice, and creating a land bridge betweenBritain and Europe (fig. 1). In the interveninginterglacials when temperatures rose the ice melted and Britain became an island for a time. Throughout these changes people and animalswandered backwards and forwards between the continent and Britain, and adapted themselves to the climate.

During the coldest times mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, reindeer and horses roamed over a treeless tundra-steppe countryside. In the warmer interglacials represented at such diverse sites as Barrington (Cambs), Victoria Cave, Settle(N.Yorks) and Trafalgar Square (London) warmth-loving animals such as the hippopotamus, straight-tusked elephant, lion, spotted hyena, bison and various species of deer flourished amongst extensive forests of birch and pine. None of the ice sheets ever covered the whole of Britain;there was always an area of southern Englandleft exposed, where animals and humans could eke out their precarious lives, each preyingon the other for food. We have a little evidenceto show that they also travelled in northernBritain, at Pontnewydd (Clwyd) for example, although the glaciers would have wiped away most traces.

The palaeolithic period

The period of human activity which began 450,000 years ago is known as the palaeolithic or Old Stone Age; it is divided into two parts. First the lower palaeolithic period, from the appearanceof the earliest people in Britain up to about 25,000 BC, when there seems to have been a break in settlement during the advance of ice in the Devensian glaciation. From around 15,000 BC occupation was resumed and the upper palaeolithic period got under way, eventually merging into the mesolithic period southern England, and Kent’s Cavern and around 8,500 BC.Westbury-sub-Mendip were both utilized. We

.Fig. 1 The extent of the ice sheets duringtheAnglian, Wolstonian and Devensian glaciations.

The people of lower palaeolithic Britain lived can imagine small, nomadic family groups folin the open air, camping beside rivers and lakes, lowing herds of animals from place to place, and wherever they had access to big game. Cave supplementingtheir meat diet by gathering sites and rock shelters are relatively rare in wild plants and berries. Animal skins and branches would have been used to make temporary shelters, since permanent sites are unlikely. Occasionally traces of camp sites have survived, such as one beside a shallow, reed-fringed lake at Caddington in Bedfordshire, where a century ago Worthington Smith found the working place of stone-tool makers, whose piles of raw material for implement making still remained as they had gathered them (fig. 2). A detailed study of tools from the site by Garth Sampson was able to show that at least three knappers (flint-tool makers) had operated at Caddington. One was an experienced craftsmanwho recognized the best flint and worked it with few mistakes. Of the two others, one was reasonably skilful whilst the other was clearly only an apprentice who made numerous mistakes.

Fig. 2 The contorted soils covering the palaeolithic floor at Caddington (Beds). A Surface soil; B Contorted glacial drift; C, E Undisturbed brick earth; D Palaeolithic land surface with piles of artefacts and flakes. At the bottom of the section are the piles of flint which men brought to the site as raw material for knapping into implements. (After Worthington Smith, 1894)

Four series of stone tools were made in Britainduring the lower palaeolithic period. The simplest are those known as Clactonian, named after a rich site beside an ancient buried river course at Clacton-on-Sea (Essex). Nodules of flint were taken and struck to detach flakes. It is these rather crude flakes that form the bulk of the Clactonian tools which were used for various cutting purposes. Sometimes the remainingcores of flint were used as chopping implements. Other Clactonian sites, all in waterside locations, have been found at Swanscombe (Kent), Barnham (Suffolk) and Little Thurrock (Essex). They seem to date from the Anglian glaciation.

Overlapping with the Clactonian tools, but surviving for a much longer period through the Hoxnian interglacial and almost to the end of the Wolstonian stage, were tools of the Acheulian industries, dominated by handaxes (fig. 3). This name is given to a variety of tools whose exact function is unknown; they did not have wooden handles and are unlikely to have been axes in the conventional modern sense. It seems more likely that they were multi-purpose tools with widely differing uses, ranging from throwing at animals to bring them down, to cutting meat and scraping skins. Handaxes were often rather crude but might also be finely chipped into elegant pear-and oval-shaped implements. They were made by detaching a series of flakes from a flint noduleuntil the core remained as the finished tool. The flakes were not wasted but made into a variety of knives, points and scrapers.

Fig. 3 Palaeolithic flint implements. A Clactonian core; B Clactonian flake tool; C Acheulian handaxe; DLevallois tortoise-shaped core; E Levallois flake tool from core.

Acheulian tools have been found at many open sites including Swanscombe (Kent), Hoxne and High Lodge (both Suffolk). The Barnfield Pit at Swanscombe has also produced three fragments of a human skull. The face is missing but expertsbelieve that it belonged to an early form of Homo sapiens, perhaps a quarter of a million years old and ancestral to Neanderthal man. Modern man, Homo sapiens sapiens, did not appear in Europeuntil about 40,000 years ago. In Kent’s Cavern at Torquay (Devon), early Acheulian tools were apparently found with the bones of bear and sabre-toothed cat.

The Levalloisian method of flint working was used in the later Acheulian. It used flake tools struck from carefully prepared cores; these cores resembled the shell of a tortoise until the desired flake tool was detached. Levallois tools are known in large numbers from a ‘factory’ site at Baker’s Hole (Northfleet, Kent), where they were found accompanied by handaxes. Both types also occurred together at Caddington (Beds) and Crayford (Kent).

In a cave in north Wales at Pontnewydd (Clwyd) late Acheulian and Levallois style tools made from volcanic pebbles have been found with a few fragments of human bone from an adult and at least three children. Dated to around 225,000 BC, these people probably belonged to the extinct human species Homo sapiens neanderthalensis or Neanderthal man. There is good reason to believe that they were members of a small group of hunters who used the cave as a shelter for very brief periods, perhaps seasonally, as they ranged freely across southern Britainand into Europe in search of game.

Probably dating to the earlier upper palaeolithic period is material from the Goat’s Cave at Paviland (Glamorgan) where the bones of mammoth, cave bear, woolly rhinoceros and elk were excavated by William Buckland in 1823.He also found the burial of a young man whose corpse had been covered with red ochre, perhapsin an effort to restore to it some appearanceof life. It lay together with a mammoth’s skull, ivory rods, shells and an ivory bracelet, which were all part of an elaborate funerary ritual.

Plate 1At least three caves in the Cheddar Gorge (Somerset) were occupied by upperpalaeolithic people. Gough’s Cave has produced more than 7,000 flint blades of Creswellian type.(J.E.Hancock)

The last handaxes to be made in Britain are attributed to the Mousterian industry. In shape they have a rather flat butt, and are sometimes known by the French name, bout coupé. Examplesare known from the Ipswich area, Little Paxton (Cambs) and Christchurch (Hants). Flake tools predominated in the Mousterian industry and are very similar to Acheulian and Levallois material.

As has already been said, there seems to have been a gap between the lower palaeolithic and the upper palaeolithic at a time when the Devensian glaciation was at its height. Some time after 15,000 BC settlement was resumed by modernman, Homo sapiens sapiens, who lived almost exclusively in cave sites. It should however be pointed out that occupation was not deep inside caves, where artificial light would always be requiredand damp conditions would have been a continual health hazard. A shelter just inside the cave mouth was favoured, where fires could be lit, and light windbreaks constructed from branches and skins (fig. 4). Dressed in furs as protection against the long icy winters, folk also ornamented themselves with bangles and necklacesmade from perforated animal teeth, carved bones and shells. Their equipment included flint tools for hunting and domestic use, including beautifully made leaf-shaped points for spears and a variety of flake scrapers, knives and gravers. An unusual object of possible ritual use was a deer antler with a hole bored through its widestend, known as a baton-de-commandement. It may also have signified social status or been used merely to straighten spear shafts. Amongst caves occupied at this time were Gough’s Cave at Cheddar(Somerset) (plate 1), the Hyena Den at Wookey (Somerset), Kent’s Cavern, Torquay (Devon), Victoria Cave (Settle, N.Yorks) (plate 2) and a number of sites at Creswell Crags (Derbyshire).

Fig. 4 Overhanging cliffs provided rock shelters, often occupied by extended family groups. Here they slept, fed and prepared tools and skins used in their daily life. (Tracey Croft)

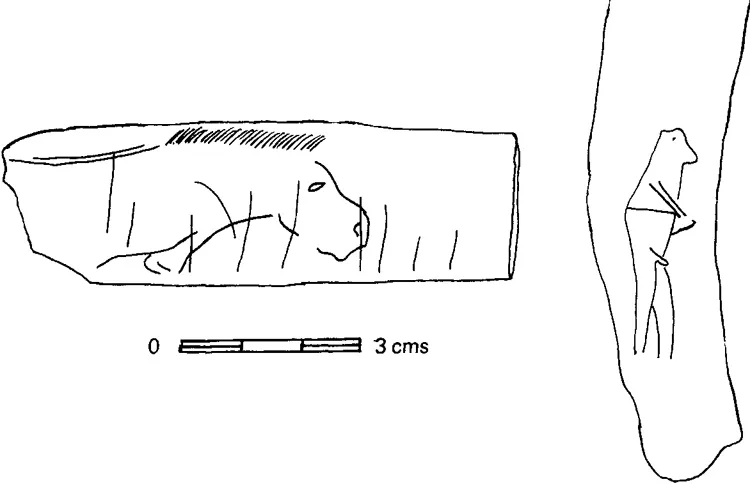

Flint work at the end of the upper palaeolithic consists largely of backed blades usually referred to as Creswellian after the Creswell Crags caves. These razor-sharp flakes had one long edge blunted, presumably for easier handling. A variety of bone tools which included harpoon heads were also being produced. At Robin Hood’s Cave (Derby) a piece of rib bone was uncovered, engraved with the forequarters and head of a wild horse resemblingthe modern day Przewalskii’s horses from Mongolia. A stylized human figure engraved on a reindeer rib and fish-like sign on an ivory point came from Pin Hole Cave (Derby). These are almost the only examples of palaeolithic art yet known in Britain: no cave paintings have ever been found (fig. 5).

Fig. 5 (below) Upper palaeolithic art consists of simple sketches on pieces of antler and bone. Left: Horse from Robin Hood’s cave; right: man from Pin Hole cave; both from Creswell Crags, Derbyshire.

The mesolithic period

At the end of the last glaciation, about 15,000 BC, the ice sheets retreated north from Scotland, and during the next 5,000 years made their way slowly towards their present-day limits in Scandinavia. The effects were decisive. The tundra and steppe which prevailed in northern Europe were slowly replaced by forest, and the herds of reindeer, bison and horse which had been the quarry of the palaeolithic hunters now retreated northwards, red deer, roe deer and wild oxen taking their place.

Palaeobotanists have worked out the long history of forest development during these early centuries, largely by analysing the pollen which has survived in peat bogs, where it was blown from neighbouring forest areas. Pollen is almost indestructible and survives in these waterlogged and acid soils. Specimens can be extracted, identifiedand counted under a microscope, where the pollen of each tree type may be seen to be unique. From the amount of each tree pollen present it is possible to reconstruct the original vegetation.

Plate 2The massive entrance to the Victoria Cave near Settle in Yorkshire. Its three chambers were occupied in the upper palaeolithic and mesolithic periods. (J.Dyer)

Between 12,000 and 9,000 BC tundra conditionsprevailed throughout Britain and the adjoiningareas of the continent. The soil was completelyfrozen except for the top metre during the summer. Plants were small and stunted and consisted of mosses and lichens and dwarf birch. By about 8,500 BC a sudden marked rise in temperature, giving warm, dry conditions, allowed the ground to thaw and fully grown birch forestsspread across northwest Europe. This periodis known to archaeologists as the pre-Boreal phase and it merged into the full Boreal period about 7,600 BC. The countryside was covered with pine forests for a time, and these then gave way to hazel and eventually mixed forests of oak, elm and lime. Changes in forest cover were clearly linked to temperature changes and by 5,000 BC when the wetter Atlantic period was well advanced the climate...