eBook - ePub

Studies in the Assessment of Parenting

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studies in the Assessment of Parenting

About this book

Offers a review of the latest literature but moreover a practical guide essential to professionals who give their expert opinions to courts in child care cases.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Studies in the Assessment of Parenting by Peter Reder, Sylvia Duncan, Claire Lucey, Peter Reder,Sylvia Duncan,Claire Lucey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Principles and practice

Chapter 1 What principles guide parenting assessments?

Peter Reder, Sylvia Duncan and Clare Lucey

Parenting assessments are a planned process of identifying concerns about a child’s welfare, eliciting information about the functioning of the parent/s and the child, and forming an opinion as to whether the child’s needs are being satisfied. This book focuses on assessments undertaken as part of Family Proceedings in order to advise courts making decisions about children’s future care. Commonly, these are hearings under the 1989 Children Act to consider whether a child has suffered significant harm as a result of the parenting they have received and whether an Order should be made to safeguard their future care. Alternatively, the hearing may be part of Matrimonial Proceedings around disputed contact arrangements between separated/divorced parents.

Assessments under the Children Act will have been preceded by front-line ‘initial’ and ‘core’ assessments in accordance with the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (Department of Health, Department for Education and Employment and Home Office, 2000; Department of Health, 2000a; Horwath, 2001; Gray, 2001). As its title indicates, this framework is concerned with ascertaining which children/families are ‘in need’ (of services), only a small proportion of whom are likely to require a child protection plan. Its core premise is that families referred to social services should be helped to remain intact and the assessment philosophy is inclined towards identifying those interventions which might help them do so. Thus, it is intentionally focused on screening referrals and selecting families that might require more detailed assessment. It allows for the possibility that services might be introduced concurrently with the assessment.

The philosophy and context of parenting assessments for court are different. The families have already been identified as showing major problems, the authority of the court adds a new dimension to the tradition of partnership between family and professionals, the assessor remains neutral throughout as to the relative strengths and weaknesses of the family, there is no bias towards any type of intervention or assumptions about the viability of the family unit, and distinction is made throughout between assessment and intervention.

Nonetheless, the spirit of the Children Act pervades all levels of assessment. The desirability of keeping families intact if possible is clear, so that cases brought before the court are expected to demonstrate that every attempt has been made to do so and all reasonable interventions have been offered and tried. A sense of partnership is now reflected in the custom of joint instruction to experts. In addition, all assessments and recommendations are expected to prioritize the child’s needs and the child’s perspective must be fully represented. The notion of significant harm to the child’s welfare and development remains a core criterion for deciding whether parenting has broken down (Bentovim, 1998; Duncan and Baker, Chapter 5).

In this opening chapter, we shall consider some of the core principles which underpin assessments for court. We shall discuss premises about parenting and parenting breakdown and the way that parenting assessments have been approached for different purposes. We shall then offer a framework to guide assessments for court and suggest how this might best be used in practice. Where relevant, indication will be given to subsequent chapters of the book which discuss issues in greater detail.

PREMISES ABOUT PARENTING

Parameters of ‘good-enough’ parenting are socially constructed, since the concept depends as much on subjective impressions, culture-bound beliefs (see Maitra, Chapter 3) and context-related thresholds of concern (Dingwall et al., 1983) as on objective qualities. We have argued elsewhere (Reder et al., 1993) that, even at the most severe end of the spectrum of parenting, the concept of ‘child abuse’ is an evolving one, with changes in definition and recognition over time. Criteria for considering what constitutes child abuse arise out of a number of social and historical contexts, such as social attitudes to children and families, theories and knowledge about child development and family functioning, and professional practice in relation to them. The ever-changing interrelationship between these dimensions is punctuated and reflected at intervals by political initiatives and changes in legislation.

A recent example is the debate about whether it is permissible to smack children, in which informed commentators hold discrepant views (e.g. Larzelere, 1996; 2000; Waterston, 2000a; 2000b; Trumbull, 2000). Conventions and legislation also vary between different countries, although some social attitudes have changed following publicity about research which showed that smacking may be counter-productive and that alternatives are effective. The relationship between advances in knowledge, public opinion and legal changes is complex. In 1979, Sweden passed legislation which abolished corporal punishment as a legitimate child-rearing practice but, according to Roberts (2000), it is erroneous to believe that the legal changes altered public opinion, since there is good evidence that support for corporal punishment had significantly declined prior to 1979. Even so, it was a ruling of the European Court of Human Rights that prompted initiatives to change British legislation (Department of Health, 2000b). Meanwhile, Cawson et al. (2000) found that 72 per cent of a sample of 18–24 year olds in the UK recalled experiencing physical forms of discipline during childhood.

Jones (2001) proposed that ‘parenting’ refers to activities and behaviours of primary caretakers necessary to achieve the objective of enabling children to become autonomous. In our view, the purpose of parenting is to facilitate the child’s optimal development within a safe environment. More specifically, according to Hoghughi (1997), the core elements of parenting are:

- Care (meeting the child’ s needs for physical, emotional and social well-being and protecting the child from avoidable illness, harm, accident or abuse);

- Control (setting and enforcing appropriate boundaries); and

- Development (realizing the child’s potential in various domains);

and, in order to be effective, the parent needs to have:

- Knowledge (e.g. how the child’s care needs can best be met, the child’s developmental potential, how to interpret the child’s cues, sources of harm);

- Motivation (e.g. to protect, to sacrifice personal needs);

- Resources (both material and personal); and

- Opportunity (e.g. time and space).

These key facets of parenting must be achieved within the evolving relationship between parent and child. The child is not a passive recipient of parental input, nor is the parent a mechanical or ubiquitous provider. For example, at one moment, the child will demand care from the parent and, later, feel satiated and claim rest. At the same time, the child’s impulses, behavioural tendencies and attitudes will be modified by the parent’s reactions and role modelling. The child and parent will elicit feelings in each other and both will attribute meaning to their experiences within the relationship. Thus, each evokes responses from the other in a reciprocal manner, through interactions that are influenced by personal qualities of each individual and by other relationships and events. The nature of their interactions varies as the child develops and the parent accommodates to this, whilst also needing to respond to changes in their own life. As in other relationships, the behaviour of one participant is bound to affect the other, even if that behaviour is hostility, indifference, rejection, or prolonged absence. Furthermore, like all relationships, the parental one is continuous in the sense that each participant carries an image of it in their mind, even when they are apart. However, it is important to recognize that the emotional relationship does not automatically depend on the blood link between child and adult, since it is primarily a function of their interpersonal history together, not their genetic history (Goldstein et al., 1973; Schaffer, 1998).

As Quinton and Rutter (1988) noted:

parenting is now understood not only to involve what parents do with their children and how they do it, but also to be affected by the quality of the parents’ relationships more generally, by their psychological functioning, by their previous parenting experiences both with other children and with a particular child, and by the social context in which they are trying to parent. (p. 8)

They went on to identify the task of parenting as being concerned with the provision of an environment conducive to children’s cognitive and social development, using skills appropriate to the handling of their distress, disobedience, social approaches, conflicts and interpersonal difficulties. Such skills are reflected in the parents’ sensitivity to their children’s cues and needs, as they change over the course of development. In addition, parenting is described as a social relationship, which is therefore affected by the parent’s previous experiences of being parented, by their current psychological state, by the child’s characteristics and by interaction with a broader social network.

Belsky and Vondra (1989) offered a coherent systemic model to describe the multiple determinants of parenting, in which individual, historical, social and circumstantial factors combine to shape parental functioning:

the model presumes that parenting is directly influenced by forces emanating from within the individual parent (personality), within the individual child (child characteristics of individuality), and from the broader social context in which the parent-child relationship is embedded—specifically the marital relations, the social networks, and occupational experiences of parents. Further, the model assumes that parents’ developmental histories, marital relations, social networks, and jobs influence their individual personalities and general psychological well-being and, thereby, parental functioning and, in turn, child development. (pp. 156–7)

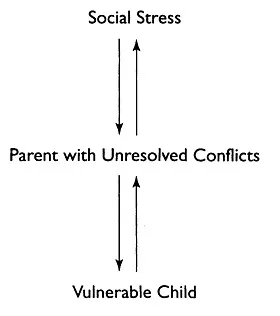

Belsky and Vondra (1989) reported an extensive review of research which identified the factors promoting optimal parenting behaviours and, in turn, outcomes for children. Even though the various studies may have used different measures of outcome—ranging from indices of children’s psychological, cognitive and behavioural development, parent-child interaction and parental attitudes and behaviours—there was good consistency in the findings that allowed Belsky and Vondra to construct a table of advantageous factors (see Table 1.1). They noted that parental competence is multiply determined and that the factors are interrelated, although the parent’s personal psychological resources are the most crucial. Maltreatment was considered to be the consequence of an interaction between stress (vulnerability or risk) factors and support (compensatory) factors. Based on these principles, we have constructed a simplified model for understanding child abuse and parenting breakdown, as shown in Figure 1.1.

No single attribute of the parent, child or family determines the quality of the parenting relationship, since it is multi-determined. Schaffer (1998) and Golombok (2000) have reviewed relevant outcome literature and concluded that family structure or individual parental attributes matter far less to children’s development than the quality of relationships within families and with the wider social world. They report that research has allowed the following inferences to be drawn.

Table 1.1 Belsky and Vondra’s (1989) summary of factors contributing to optimal child care outcomes

Being the child of a single parent is not per se a risk factor for the child’s development and welfare. Exposure to continuing parental conflict is more harmful than the fact of divorce/separation or the nature of custody arrangements and it is the associated financial hardship that often renders single parental status problematic.

Fathers are just as capable of effective and sensitive parenting as mothers, so that if both divorced parents apply for prime responsibility to care for their child, it is not the parent’s sex but their individual circumstances that matter.

Source: Reder and Duncan (1999).

Figure 1.1 A model of parenting breakdown

- The father’s presence in, or absence from, the home does not make a significant difference in itself to a child’s gender identity, sex role development, or general psychological outcome.

- Being cared for by homosexual partners (whether early or late in childhood) makes no difference to the young person’s gender identity or psychological stability.

- Consanguinity confers no emotional advantage to the child over pregnancy achieved artificially, although there remains an absence of studies on surrogacy.

- Step-children are more likely to show problems if their family was reconstituted later in their upbringing.

- The figure whom the child regards as their parent depends much more on their social, not their genetic, relationship.

- It is the totality of a child’s experience that is relevant to their emotional development and well-being rather than si...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- PART I: PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE

- PART II: THE CHILD’S PERSPECTIVE

- PART III: ASSESSING PARENTS

- PART IV: RECOMMENDATIONS

- PART V: JUDGMENTS