1: Setting the scene

The nations of the world came together in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED)—dubbed the Earth Summit—to try to reach consensus on the best way to slow down, halt and eventually reverse ongoing environmental deterioration. The Summit represented the culmination of two decades of development in the study of environmental issues, initiated at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972. Stockholm was the first conference to draw worldwide public attention to the immensity of environmental problems, and because of that it has been credited with ushering in the modern era in environmental studies (Haas et al. 1992).

The immediate impact of the Stockholm conference was not sustained for long. Writing in 1972, the climatologist Wilfrid Bach expressed concern that public interest in environmental problems had peaked and was already waning. His concern appeared justified as the environmental movement declined in the remaining years of the decade, pushed out of the limelight in part by growing fears of the impact of the energy crisis. Membership in environmental organizations—such as the Sierra Club or the Wilderness Society—which had increased rapidly in the 1960s, declined slowly, and by the late 1970s the environment was seen by many as a dead issue (Smith 1992). In the 1980s, however, there was a remarkable resurgence of interest in environmental issues, particularly those involving the atmospheric environment. The interest was broad, embracing all levels of society, and held the attention of the general public, plus a wide spectrum of academic, government and public-interest groups.

Most of the issues were not entirely new. Some, such as acid rain, the enhanced greenhouse effect, atmospheric turbidity and ozone depletion, had their immediate roots in the environmental concerns of the 1960s, although the first two had already been recognized as potential problems in the nineteenth century. Drought and famine were problems of even longer standing. Contrasting with all of these was nuclear winter—a product of the Cold War—which remained an entirely theoretical problem, but potentially no less deadly because of that.

Diverse as these issues were, they had a number of features in common. They were, for example, global or at least hemispheric in magnitude, large scale compared to the local or regional environmental problems of earlier years. All involved human interference in the atmospheric component of the earth/atmosphere system, and this was perhaps the most important element they shared. They reflected society’s ever-increasing ability to disrupt environmental systems on a large scale.

These issues are an integral part of the new environmentalism which has emerged in the early 1990s. It is characterized by a broad, global outlook, increased politicization—marked particularly by the emergence of the so-called Green Parties in Europe—and a growing environmental consciousness which takes the form of waste reduction, prudent use of resources and the development of environmentally safe products (Marcus and Rands 1992). It is also a much more aggresive environmentalism, with certain organizations—Green-peace and Earth First, for example—using direct action in addition to debate and discussion to draw attention to the issues (Smith 1992).

Another characteristic of this new environmentalism is a growing appreciation of the economic and political components in environmental issues, particularly as they apply to the problems arising out of the economic disparity between the rich and poor nations. The latter need economic development to combat the poverty, famine and disease that are endemic in many Third World countries, but do not have the capacity to deal with the environmental pressures which development brings. The situation is complicated by the perception among the developing nations that imposition of the environmental protection strategies proposed by the industrial nations is not only forcing them to pay for something they did not create, but is also likely to retard their development,

Table 1.1 Treaties signed at the world environment meetings in Rio de Janeiro—June 1992

Development issues were included in the Stockholm conference in 1972, but they were clearly of secondary importance at that time, well behind all of the environmental issues discussed. Fifteen years later, the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development—commonly called the Brundtland Commission after its chairwoman, Gro Harlem Brundtland—firmly combined economy and environment through its promotion of ‘sustainable development’, a concept which required development to be both economically and environmentally sound so that the needs of the world’s current population could be met without jeopardizing those of future generations. The Brundtland Commission also proposed a major international conference to deal with such issues. This led directly to the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, and its parallel conference of non-governmental organizations (NGOs)—the Global Forum.

The theme of economically and environmentally sound development was carried through the Summit to the final Rio Declaration of global principles and to Agenda 21, the major document produced by the conference, and basically a blueprint for sustainable development into the twenty-first century. That theme also appeared in other documents signed at Rio, including a Framework Convention on Climate Change brought on by concern over global warming, a Biodiversity Convention which combined the preservation of natural biological diversity with sustainable development of biological resources, and a Statement of Forest Principles aimed at balancing the exploitation and conservation of forests. Discussions and subsequent agreements at the Global Forum included an equally wide range of concerns (see Table 1.1).

There can be no assurance that these efforts will be successful. Even if they are, it will be some time—probably decades—before the results become apparent, and success may have been limited already by the very nature of the various treaties and conventions. For example, both the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 were the result of compromise among some 150 nations. Attaining sufficient common ground to make this possible inevitably weakened the language and content of the documents, leaving them open to interpretation and therefore less likely to be effective (Pearce 1992b). The failure of the developed nations to commit new money to allow the proposals contained in the documents to go ahead is also a major concern (Pearce 1992a). Perhaps this lack of financial commitment is a reflection of the recessionary conditions of the early 1990s, but without future injections of funds from the developed nations, the necessary environmental strategies will not be implemented, and Third World economic growth will continue to be retarded (Miller 1992). Other documents are little more than statements of concern with no legal backing. The forestry agreement, for example, is particularly weak, largely as a result of the unwillingness of the developing nations to accept international monitoring and supervision of their forests (Pearce 1992a). The end product remains no more than a general statement acknowledging the need to balance the exploitation of the forests with their conservation. Similarly, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed only after much conflict among the participants, was much weaker than had been hoped—lacking even specific emission reduction targets and deadlines (Warrick 1993).

Faced with such obstructions to progress from the outset, the Rio Summit is unlikely to have much direct impact in the near future. When change does come it is unlikely to come through such wide-ranging international conferences where rhetoric often exceeds commitment. It is more likely to be achieved initially by way of issue-specific organizations, and the Earth Summit contributed to progress in that area by establishing a number of new institutions—the Sustainable Development Commission, for example—and new information networks. By bringing politicians, non-governmental organizations and a wide range of scientists together, and publicizing their activities by way of more than 8,000 journalists, the Summit also added momentum to the growing concern over global environmental issues, wiithout which future progress will not be possible.

THE IMPACT OF SOCIETY ON THE ENVIRONMENT

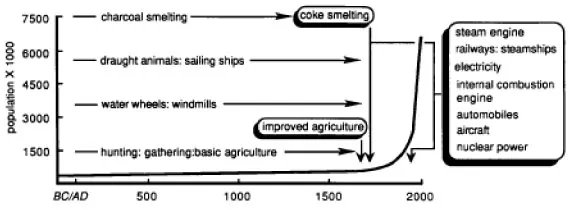

Society’s ability to cause significant disruption in the environment is a recent phenomenon, strongly influenced by demography and technological development. Primitive peoples, for example, being few in number, and operating at low energy levels with only basic tools, did very little to alter their environment. The characteristically low natural growth rates of the hunting and gathering groups who inhabited the earth in prehistoric times ensured that populations remained small. This, combined with their nomadic lifestyle, and the absence of any mechanism other than human muscle by which they could utilize the energy available to them, limited their impact on the environment. In truth, they were almost entirely dominated by it. When it was benign, survival was assured. When it was malevolent, survival was threatened. Population totals changed little for thousands of years, but slowly, and in only a few areas at first, the dominance of the environment began to be challenged. Central to that challenge was the development of technology which allowed the more efficient use of energy (see Table 1.2). It was the ability to concentrate and then expend larger and larger amounts of energy that made the earth’s human population uniquely able to alter the environment. The ever-growing demand for energy to maintain that ability is at the root of many modern environmental problems (Biswas 1974).

Table 1.2 Energy use, technological development and the environment

Figure 1.1 World population growth and significant technological developments

The level of human intervention in the environment increased only slowly over thousands of years, punctuated by significant events which helped to accelerate the process (see Figure 1.1). Agriculture replaced hunting and gathering in some areas, methods for converting the energy in wind and falling water were discovered, and coal became the first of the fossil fuels to be used in any quantity. As late as the mid-eighteenth century, however, the environmental impact of human activities seldom extended beyond the local or regional level. A global impact only became possible with the major developments in technology and the population increase which accompanied the so-called Industrial Revolution. Since then—with the introduction of such devices as the steam engine, the electric generator and the internal combustion engine—energy consumption has increased sixfold, and world population is now five times greater than it was in 1800. The exact relationship between population growth and technology remains a matter of controversy, but there can be no denying that in combination these two elements were responsible for the increasingly rapid environmental change which began in the mid-eighteenth century. At present, change is often equated with deterioration, but then technological advancement promised such a degree of mastery over the environment that it seemed such problems as famine and disease, which had plagued mankind for centuries, would be overcome, and the quality of life of the world’s rapidly expanding population would be improved infinitely. That promise was fulfilled to some extent, but, paradoxically, the same technology which had solved some of the old problems, exacerbated others, and ultimately created new ones.

THE RESPONSE OF THE ENVIRONMENT TO HUMAN INTERFERENCE

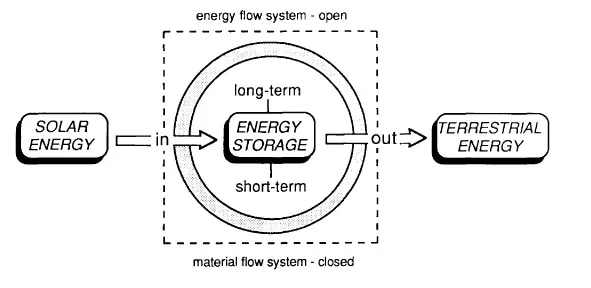

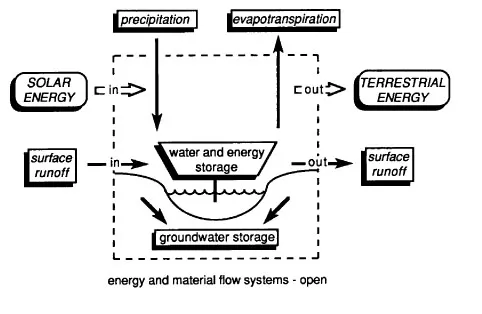

The impact of society on the environment depends not only on the nature of society, but also on the nature of the environment. Although it is common to refer to ‘the’ environment, there are in fact many environments, and therefore many possible responses to human interference. Individually, these environments vary in scale and complexity, but they are intimately linked, and in combination constitute the whole earth/ atmosphere system (see Figure 1.2). Like all systems, the earth/atmosphere system consists of a series of inter-related components or subsystems, (see Figure 1.3) ranging in scale from microscopic to continental, and working together for the benefit of all. Human interference has progressively disrupted this beneficial relationship. In the past, disruption was mainly at the sub-system level—contamination of a river basin or pollution of an urban environment, for example—but the integrated nature of the system, coupled with the growing scale of interference caused the impact to extend beyond individual environments to encompass the entire system.

In material terms the earth/atmosphere is a closed system, since it receives no matter (other than the occasional meteorite) from beyond its boundaries. The closed nature of the system is of considerable significance, since it means that the total amount of matter in the system is fixed. Existing resources are finite; once they are used up they cannot be replaced. Some elements—for example, water, carbon, nitrogen, sulphur—can be used more than once because of the existence of efficient natural recycling processes which clean, repair or reconstitute them. Even they are no longer immune to disruption, however. Global warming is in large part a reflection of the inability of the carbon cycle to cope with the additional carbon dioxide introduced into the system by human activities.

The recycling processes and all of the other sub-systems are powered by the flow of energy through the system. In energy terms the earth/ atmosphere system is an open system, receiving energy from the sun and returning it to space after use. When the flow is even and the rates of input and output of energy are equal, the system is said to be in a steady state. Because of the complexity of the earth/atmosphere system, the great number of pathways available to the energy and the variety of short and long-term storage facilities that exist, it may never actually reach that condition. Major excursions away from a steady state in the past may be represented by such events as the Ice Ages, but in most cases the responses to change are less obvious. Changes in one element in the system, tending to produce instability, are countered by changes in other elements which attempt to restore balance. This tendency for the components of the environment to achieve some degree of balance has long been recognized by geographers, and referred to as environmental equilibrium. The balance is never complete, however. Rather, it is a dynamic equilibrium which involves a continuing series of mutual adjustments among the elements that make up the environment. The rate, nature and extent of the adjustments required will vary with the amount of disequilibrium introduced into the system, but in every environment there will be periods when relative stability can be maintained with only minor adjustments. This inherent stability of the environment tends to dampen the impact of changes even as they happen, and any detrimental effects that they produce may go unnoticed. At other times, the equilibrium is so disturbed that stability is lost, and major responses are required to restore the balance. Many environmentalists view the present environmental deterioration as the result of human interference in the system at a level which has pushed the stabilizing mechanisms to their limits, and perhaps beyond.

Figure 1.2 Schematic diagram of the earth/atmosphere system

Figure 1.3a Schematic diagram of a natural subsystem—a lake basin

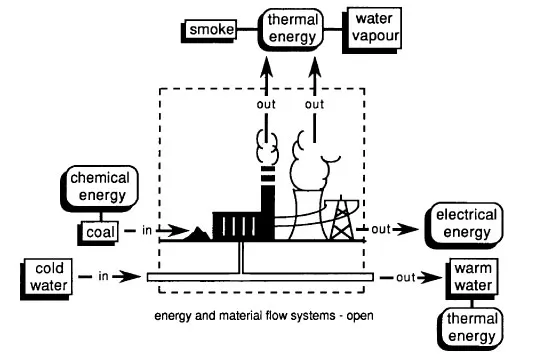

Figure 1.3b Schematic diagram of a subsystem of anthropogenic origin—a thermal electric power plant

Running contrary to this is the much less pessimistic point of view expressed by James Lovelock and his various collaborators in the Gaia hypothesis (Lovelock 1972; Lovelock and Margulis 1973). First developed in 1972, and named after an ancient Greek earth-goddess, the hypothesis views the earth as a single organism in which the individual elements exist together in a symbiotic relationship. Internal control mechanisms maintain an appropriate level of stability. Thus, it has much in common with the concept of environmental equilibrium. It goes further, however, in presenting the biocentric view that the living components of the environment are capable of working actively together to provide and retain optimum conditions for their own survival. Animals, for example, take up oxygen during respiration and return carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. The process is reversed in plants, carbon dioxide being absorbed and oxygen released. Thus, the waste product from each group becomes a resource for the other. Working together over hundreds of thousands of years, these living organisms have combined to maintain oxygen and carbon dioxide at levels capable of supporting their particular forms of life. This is one of the more controversial aspects of Gaia, flying in the face of majority scientific opinion—which, since at least the time of Darwin, has seen life responding to environmental conditions rather than initiating them—and inviting some interesting and possibly dangerous corollaries. It would seem to follow, for example, that existing environmental problems which threaten life—ozone depletion, for example—are transitory, and will eventually be brought under control again by the environment itself. To accept that would be to accept the efficacy of regulatory systems which are as yet unproven, particularly in their ability to deal with large scale human interference. Such acceptance would be irresponsible, and has been referred to by Schneider (1986) as ‘environmental brinksmanship’.

Lovelock himself has allowed that Gaia’s regulatory mechanisms may well have been weakened by human activity (Lovelock and Epton 1975; Lovelock 1986). Systems cope with change most effectively when they have a number of options by which they can take appropriate action, and this was considered one of the main strengths of Gaia. It is possible, however, that the earth’s growing population has created so much stress in the environment, that the options are much reduced, and the regulatory mechanisms may no longer be able to nullify the threats to balance in the system. This reduction in the variety of responses available to Gaia may even have cumulative effects which could threaten the survival of human species. Although the idea of the earth as a living organism is a basic concept in Gaia, the hypothesis is not anthropocentric. Humans are simply one of the many forms of life in the biosphere, and whatever happens life will continue to exist, but it may not be human life. For example, Gaia includes mechanisms capable of bringing about the extinction of those organisms which adversely affect the system (Lovelock 1986). Since the human species is currently the source of most environmental deterioration, the partial or complete removal of mankind might be Gaia’s natural answer to the earth’s current problems.

The need for coexistence between people and the other elements of the environment, now being advocated by Lovelock as a result of his research into Gaia, has been accepted by several generations of geographers, but historically society has tended to view itself as being in conflict with the environment. Many primitive groups may have enjoyed a considerable rapport with their environment, but, for the most part, the relationship was an antagonistic one (Murphey 1973; Smith 1992). The environment was viewed as hos...