- 486 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Teaching Online: A Practical Guide is an accessible, introductory, and comprehensive guide for anyone who teaches online. The fourth edition of this bestselling resource has been fully revised, maintains its reader-friendly tone, and offers exceptional practical advice, new teaching examples, faculty interviews, and an updated resource section.

New to this edition:

-

- entire new chapter on MOOCs (massive open online courses);

-

- expanded information on teaching with mobile devices, using open educational resources, and learning analytics;

-

- additional interviews with faculty, case studies, and examples;

-

- spotlight on new tools and categories of tools, especially multimedia.

Focusing on the "hows" and "whys" of implementation rather than theory, the fourth edition of Teaching Online is a must-have resource for anyone teaching online or thinking about teaching online.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

Getting Started

1

Teaching Online: An Overview

While online education delivered via the internet has been around for about two decades, many people still don’t know exactly what it is, or how it’s done, or even what some of the terms used to describe it mean. The MOOC craze of recent years heightened the awareness of many to the possibilities of online learning, but muddied the waters when popular commentators, in debating the merits or perils of online learning, often failed to distinguish between the pre-existing model of small-scale online courses led by instructors and these new opportunities in which thousands or even tens of thousands of would-be learners might be involved.

Some faculty may now have a general notion of what’s involved in online education, but they don’t know how to get started, or they feel some trepidation about handling the issues they may encounter. And there are now many who have taught online, but feel that they have barely scratched the surface in terms of learning how best to adapt their teaching to the new environment. Perhaps this range of feelings exists in part because the online environment is so different from what most instructors have encountered before.

MOOC—Massive Online Open Course—an online course in which large numbers of people (hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands) may freely enroll without charge. Some MOOCs are not really open in that they are either limited to certain users or charge a fee.

Teaching online means conducting a course partially or entirely through the internet—either on the Web or by way of mobile apps that allow one to manipulate the online course elements. You may also see references to online education as eLearning (electronic learning), a term often used in business. It’s a form of distance education, a process that traditionally included courses taught through the mail, by DVD, or via telephone or TV—any form of learning that doesn’t involve the traditional classroom setting in which students and instructor must be in the same place at the same time.

app—mobile apps are application software that are downloaded to a tablet or smartphone and designed to perform specific functions. These functions may duplicate those that can be performed in the internet browser version of a program but are generally optimized to operate in the mobile environment.

What makes teaching online unique is that when you teach online, you don’t have to be someplace to teach. You don’t have to lug your briefcase full of papers or your laptop to a classroom, stand at a lectern, scribble on a chalkboard (or even use your high-tech, interactive classroom “smart” whiteboard), or grade papers in a stuffy room while your students take a test. You don’t even have to sit in your office waiting for students to show up for conferences. You can hold “office hours” on weekends or at night after dinner. You can do all this while living in a small town in Wyoming or a big city like Bangkok, even if you’re working for a college whose administrative offices are located in Florida or Dubai. You can attend an important conference in Hawaii on the same day that you teach your class in New Jersey, logging on from your laptop via the local café’s wireless hot spot or your hotel room’s high-speed network. Or you may simply pull out your smartphone to quickly check on the latest postings, email, or text messages from students, using a mobile app for your course site or to access other resources.

Online learning offers more freedom for students as well. They can search online for courses using the internet, scouring their institutions or even the world for programs, classes, and instructors that fit their needs. Having found an appropriate course, they can enroll and register, shop for their books (whether hard copy or ebooks), read articles, listen to lectures, submit their homework assignments, confer with their instructors, and access their final grades—all online.

They can assemble in virtual classrooms, joining other students from diverse geographical locales, forging bonds and friendships not possible in conventional classrooms, which are usually limited to students from a specific geographical area. Online learning activities may be conducted in asynchronous format, allowing for access and posting by students at different times during the week, or via synchronous sessions or a combination of both.

The convenience of learning online applies equally well to adult learners, students from educationally underserved areas, those pursuing specialized or advanced degrees, those who want to advance in their degree work through credentialed courses, and any students who simply want to augment the curricular offerings from their local institutions. No longer must they drive to school or remote classroom, find a parking space, sit in a lecture hall at a specific time, wait outside their instructors’ offices for conferences, and take their final exams at the campus. They can hold a job, have a family, take care of parents or pets, and even travel. As long as they can get to a computer or other device connected to the internet, students can, in most cases, keep up with their work even if they’re busy during the day. School is always in session because school is always there.

So dynamic is the online environment that new technologies and techniques are emerging all the time. What’s commonplace one year becomes old hat the next. The only thing that seems to remain constant is people’s desire to transmit and receive information efficiently, to learn and to communicate with others, no matter what the means. That’s what drives people to shop, invest, and converse online, and it is this same force that is propelling them to learn online as well.

Online education is no longer a novelty. In the United States alone, over 27 percent of college students took at least one distance learning course in fall of 2013, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, while the Babson Survey of February 2015 noted that even while the overall rate of growth had slowed in recent years, online education remained at high levels in public four- and two-year institutions, with both public and private four-year institutions exhibiting the highest levels of growth (see www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradelevel.pdf).

Worldwide, online learning is taking place in a variety of environments and combinations. There are students using mobile devices to communicate and collaborate with instructors and classmates, others gathering in local computer labs to connect with central university resources to bring previously unavailable classes to far-flung portions of a nation, and there are degree programs offered fully online for which students need never set foot on a physical campus. Open or “mega” universities providing alternate routes for higher education to hundreds of thousands of students in such countries as India, Indonesia, Turkey, and other nations use a variety of different distance education methods, online increasingly among them, to deliver courses, certificates, and degrees.

But all this freedom and innovation can sometimes be perplexing. If the conventional tools of teaching are removed, how do you teach? If school’s open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, when is school out? What is the role of the instructor if you don’t see your students face to face? Do you simply deliver lectures and grade papers, following in the traditional pattern, or do you take on other roles, for example, that of a facilitator, moderator, or mentor?

And what if you’re among the many instructors who teach face to face but maintain an internet site or blog as well? Does making your course notes available online mean that coming to class will become obsolete? How do you balance the real and virtual worlds so that they work together? And if information can be presented readily online, what should class time be devoted to: Discussions? Student presentations? Structured debates? Even more challenging, if your course is conducted and class activities occur both online and in face-to-face sessions, how do you create a blended learning experience for your students that is integrated and coherent?

There is no prototypical experience of teaching online. Some instructors use the internet to complement what they teach in class or to replace some of the “seat time.” Others teach entirely online. Some institutions offer the latest software, support, and training to instructors; others offer little more than the bare bones to instructors.

You will get a sense of these differences in the chapters that follow. For the time being, take a look at two hypothetical instructors working online.

The Range of Online Experiences: Two Hypothetical Cases

The first of our hypothetical instructors, Jim Hegelmarks, teaches philosophy entirely online. The second, Miriam Sharpe, teaches a first-year physics course in a conventional classroom but uses a learning management system (LMS) to replace some face-to-face class time and to help her students review material and get answers to their questions.

Western Philosophy, a Course Taught Entirely Online

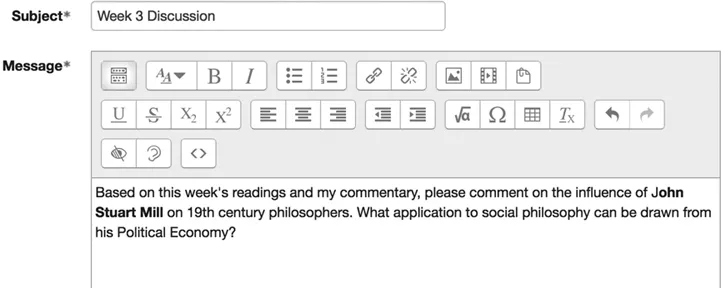

Jim Hegelmarks’s course in Western philosophy is now in its third week, and the assignment for his class is to read a short commentary he has written on John Stuart Mill’s Principles of Political Economy, portions of which the class has studied. He has asked the students to read his commentary and then respond in some detail to a question he has posted on the online discussion board for his course.

Connecting to the internet from his home, or sitting in a local coffee shop with his laptop and wireless connection, Hegelmarks types the URL of his class website into the location bar of his Firefox browser and is promptly greeted with a log-in screen. He types in his user name (jhegelmarks) and his password (hmarks420); this process admits him to the class.

Hegelmarks’s course is conducted using a learning management system (or virtual learning environment) which his university has adopted for all online courses.

Learning management system or software (LMS), also known as virtual learning environment (VLE), learning management system (LMS), learning platform, online delivery system A software program that contains a number of integrated instructional functions. Instructors can post lectures or graphics, moderate discussions, invoke chat sessions, post video commentary, and give quizzes, all within the confines of the same software system. Not only can instructors and students “manage” the flow of information and communications, but the instructor can both assess and keep track of the performance of the students, monitoring their progress and assigning grades. Typical examples of an LMS are those produced by Blackboard and Canvas, or adopted from “open source” products such as Moodle or Sakai. Your institution may have yet another proprietary system of its own, and there are many others in use or being developed all over the world. These systems, as well as many of the tools which are continually being added to these systems, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

Figure 1.1 Jim Hegelmarks creates a discussion topic using Moodle software. Reproduced by permission from Moodle.

The main page of Hegelmarks’s course contains a number of navigational links on a class site menu that he can use to manage the course. His commentary is posted in a section that is set up to display text or audio lectures, but the area he’s interested in today is the discussion board, so that’s where he goes first. With his mouse, he clicks on the menu link that leads to the discussion board and reviews the messages that have been posted there. Several of the students have posted their responses to the assignment. He reads through the responses on-screen thoughtfully, printing out the longer ones so that he can consider them at his leisure. Each posting is about fifty words in length although he has a few students who post more lengthy replies.

After evaluating the responses, Hegelmarks gives each student a grade for this assignment and enters the grade in the online gradebook, which can be reached by clicking another navigational link on the course’s main page menu. Each type of graded assignment, including participation, has a section reserved for it in the online gradebook. He knows that when students log on to the class website to check their grades, each student will be able to see only his or her own grades—no one else’s grade will be visible. Hegelmarks also knows that those who have failed to complete this assignment will be able to monitor their progress, or lack of it, by looking at the gradebook online.

What concerns Hegelmarks now is that only five of his fifteen students have responded so far. Because it’s already Friday, and there’s a new assignment they must do for the next week, he decides to take a look at some of the statistical information that the learning management system offers for tracking student progress. What he finds is that of the ten students who haven’t responded to the question, eight have at least clicked on (and one hopes, actually read) the commentary for that lesson, some spending more than sixty minutes at a time in that area. Two haven’t looked at it at all.

Hegelmarks’s first concern is with the two students who haven’t even looked at the assigned commentary. It isn’t the first time they’ve failed to complete an assignment on time. Hegelmarks sends both of them a low-key but concerned email asking whether they’re having any special problems he should know about, gently reminding them that they’ve fallen behind.

The lengthy time the other students have been taking to read his commentary concerns him as well. From experience, he knows that students often struggle with some of the concepts in Mill’s Political Economy. He had written the commentary and created the homework assignment in an attempt to clarify the subject, but taking a second look, he now realizes that the commentary was written far too densely. He makes a note to rewrite it the next time he teaches the class.

While Hegelmarks is still online, a student instant messages him, using that feature of this learning management software, and Hegelmarks takes a few minutes to answer a question about the upcoming assignment. The question had been addressed in the classroom Q&A area, and in fact, the student seems to know the answer already, but he is grateful to receive Heg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- PART I Getting Started

- PART II Putting the Course Together

- PART III Teaching in the Online Classroom

- Glossary

- Guide to Resources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching Online by Susan Ko,Steve Rossen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.