![]()

1

COLONIZING ‘NATION’

De Voortrekkers (1916)

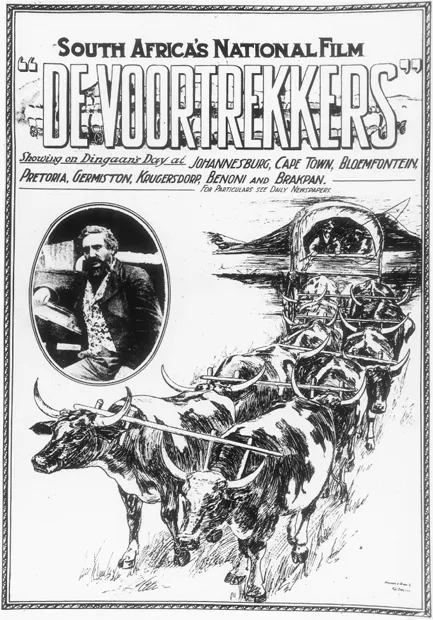

The first appropriation of the cinema as an instrument for representing nation in South Africa must surely be the making of De Voortrekkers in 1916, by AFP. As we can see from the publicity poster (Figure 1.1), it promulgated an exclusive perception of nation. The film historian Thelma Gutsche also gave it a ‘national’ ascription when she asserted that the film is ‘in every sense a national film documenting a climatic point in South African history’ [my emphasis] (Gutsche 1972: 313). Her reference to the film as ‘national’ is based on its epic historical narrative that might be seen as documenting one of South Africa’s most significant colonial wars, and memorialized for the generations that followed. The ‘national’ significance of the northwards migration of the Boers from the Cape Colony (towards Natal) is emphasized in the film where it is described as a ‘national movement to the North’ [my emphasis] in one of the inter-titles. This ‘national’ descriptor elevates this movement into a more grandiose status than would necessarily otherwise have been the case.

It is significant that the film was released in England and America under the English title, Winning a Continent, signifying much broader colonial aspirations. This is underscored by an inter-title within the film following scenes of what became known as the ‘Battle of Blood River’ (in effect the Ncome River) that reads: ‘The Men who Conquered a Continent’, thereby exaggerating the apparent heroism of the Boers. A complex interplay of possible meanings emerges in relation to this title. Strebel for example comments that it ‘is indicative of Afrikaner imperialist ambitions and self-confidence building’ (1979: 27). Tomaselli, on the other hand, calls this an ‘inapposite assumption’, arguing that Strebel ‘dismisses the importance of English capital which financed the film’ (1986: 38).1 Tomaselli opens up a critical debate about the film’s representation of British ‘culpability’, first for the migration of the Boers from the Cape Colony and second for the events that ensued in Zululand.2 Conflict between Boer and Briton is expediently downplayed in the film in order to ensure its marketability in Britain. As Tomaselli notes, Britain was the film’s primary market, from which it garnered ‘an unexpected high profit’ (Tomaselli 1986: 43 n. 24). For Tomaselli, critics like Strebel wrongly attribute ‘all of South Africa’s ills to Afrikaners rather than as a manifestation of the internationalization of capital’ (1986: 38) and ultimately the film has ‘more to do with imperial ideology than with Afrikaner Nationalism’ (Tomaselli 1986: 38). This is a compelling debate and certainly a critical one, since the film does fluidly brush aside or even ignore the basis for the migration of the Boers. It is instructive that at the time of the film’s release a British critic noted that the reasons for the Boer leaders’ ‘venture’ into Zululand ‘are most discreetly disregarded’ (The Bioscope, 13 September 1917: 16), which implies that the filmmakers were seen to be making a conscious choice not to incorporate Britain’s responsibility for the historical events portrayed. AFP clearly supported unity between Afrikaners and English-speaking South Africans post Union and this was not simply expedient on their part for marketing the film in Britain, but also congruent with white political sentiment against the perceived ‘threat’ of black political advancement. AFP’s allegiances were with the new South African Party (SAP), leading the Union under Botha and Smuts, and then increasingly with the National Party (NP) led by Hertzog. Both the SAP and the NP were variously committed to white supremacy.3

Figure 1.1 De Voortrekkers (1916) poster. Courtesy of M-Net (Electronic Media Network).

The film’s importance as a propaganda piece for Afrikaner nationalism is reflected by its deployment as cultural signifier. It premièred at the Krugersdorp Town Hall on 16 December 1916, celebrating the inauguration of the Paardekraal Monument, symbolic of the stand taken against the British by the Boers on 16 December 1880, when they hoisted the flag of the South African Republic at Paardekraal in defiance of British occupation. The repetitious annual memory cycle on 16 December commemorated the day of victory in the ‘Battle of Blood River’, which was set aside as a public holiday called ‘Dingaan’s Day’, after Dingane, the Zulu king (anomalously from the Afrikaner perspective).4 It was later called the ‘Day of the Covenant’ and the ‘Day of the Vow’, and was often accompanied by screenings of the film. The film was also screened as part of the celebrations at the laying of the foundation stone for the Voortrekker Monument in 1938, the centennial of the battle in 1838. This was an excessively grand occasion, which included the re-enactment of the so-called ‘Great Trek’ with nine ox-wagon treks starting in different cities and ending up at the Voortrekker Monument itself (one of them at the Ncome River). It was thus culturally that the film made its biggest mark, sutured into the growing nationalist sentiments of the Afrikaner ‘community’. It was what Gaines calls a ‘mass consciousness builder’ (2000: 303).

De Voortrekkers projects notions of national identity through particular images, which typify categorizations of South African identities that had already been put in place by 1916. It inscribes national borderlines and boundaries in the interests of a certain history and national identity, predicated on erasing other histories and identities. The film’s ideological perspective is that of the Boers, an epic cinematic tale from the colonizer’s/settler’s point of view. It thus set the scene for a national cinema that was to be (mostly) limited to this framing, bound up within the ideological necessities of claiming supremacy for the white Afrikaner minority as against the black majority. It was this film then that set the course for South Africa’s national cinema for most of the twentieth century.

De Voortrekkers (1916) and The Birth of a Nation (1915)

De Voortrekkers has been compared with D.W. Griffith’s (in)famous film The Birth of a Nation (1915) that represents white supremacy in the American South. Indeed, Strebel calls De Voortrekkers ‘a South African Birth of a Nation (sic)’ (1979: 25), while more recently Gaines calls it The Birth of a Nation’s ‘South African equivalent’ (2000: 298). This relationship is not altogether coincidental, however. Ndugu Ssali, for example, comments: ‘[i]f there was a filmmaker in the world with whom South Africa fell in love, it was the American film-maker D.W. Griffith’ (1996: 95). This is confirmed by Thelma Gutsche’s assertion that Griffith’s reputation ‘approached that of fetishism’ (1972: 140). The fact that at least one of the commentators, whose views were recorded when De Voortrekkers was released, confidently compared it with The Birth of a Nation, suggests that such comparisons were possibly broadly in circulation: ‘I have seen “The Birth of a Nation” and I think “The Voortrekkers” is a greater film’ (Stage and Cinema, 23 December 1916: 2).5 Another commentator announced that he had not seen The Birth of a Nation but still took the liberty of pronouncing De Voortrekkers a better film (Stage and Cinema, 16 December 1916: 9).

For all the comparisons, however, it is difficult to ascertain exactly when The Birth of a Nation was first screened in South Africa. The fact that it appears to have been screened for the first time as late as 1931 seems odd. Nevertheless, Gutsche lists it in her appendix of outstanding films screened in 1931 (1972: 230), although it is possible that it may have been a shortened sound version (Hees 2003: 66 n. 4). The screening raised controversy, notably through the critique of Solomon Plaatje published in Umteteli wa Bantu on 18 July 1931. He asserted that the film ‘glorifies the early outrages of the Ku Klux Klan . . . [and] . . . ugly black peril scenes are shown until the emotions of white people are worked up to fever heat’ (quoted in Masilela 2003: 21). For Plaatje, Dixon, who wrote The Clansman (1905), the story on which The Birth of a Nation is based, was ‘the avowed champion of American Negrophobes’ (quoted in Peterson 2003: 44). Citing that the film had been banned or censored in the USA, Plaatje questioned whether it was ‘licensed to fan the embers of race hatred in South Africa’ (Peterson 2003: 44).

While Griffith pushed film technology forward in The Birth of a Nation, making an historical mark on the history of film, he also fuelled racism towards blacks by representing them variously as servile and colluding with their white masters and mistresses, or as brutish, sexualized bucks, notably in the role of Gus (Walter Long) who threatens the young Flora Cameron (Mae Marsh) and is deemed to have raped her. The tension that Griffith creates in the way that she flees Gus juxtaposed against his stalking, and the aftermath when she throws herself off a cliff, very strongly suggests rape. But at least one critic has proposed a far more complex argument for what occurs between Gus and Flora, which relates too in some measure to De Voortrekkers and I shall return to this later.

What then are the comparative points between De Voortrekkers and The Birth of a Nation? To what extent, and how, are they both about ‘birthing nations’?6 On the surface there are two obvious general similarities: both films expound and promote racist views in the furtherance of a white supremacist cause and the promotion of an exclusively white ‘nation’; and both exploit black people as ‘others’ against which white identity is confirmed and celebrated. The Birth of a Nation sparked widespread protest in the USA at the time of its release, spearheaded by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).7 Edwin Hees (2003) provides a valuable comparative account in more specific terms. Both films, for example, end with the creation of a new nuclear family. In the case of The Birth of a Nation it is in fact two, when we see the two wedding couples on honeymoon at the end. This is the ‘culmination of the personal and political stories’ (Hees 2003: 57), thus both filmmakers tie the filmic narrative ‘journey’ in with the politically motivated over-arching narrative that exceeds the frame, the formation or ‘birth’ of a nation, and furthermore, one that is God-given, ‘end[ing] with a clear religious sanction for a new “nation” ’ (Hees 2003: 58). Both films too can be seen as expressions of nostalgia for a glorified and mythologized past. Gaines suggests, in the case of The Birth of a Nation, that this ‘nostalgia’ is for ‘Southern plantation life long gone’ while De Voortrekkers ‘is enamoured with the Great Trek’ (2000: 301). But this is not just empty nostalgia. In De Voortrekkers it represents ‘the expression of pioneer courage that justified the Boers’ entitlement to land and consequently their imagination of nation’ (Gaines 2000: 301).

As we proceed to analyse how De Voortrekkers defines ‘nation’ we will see that its suppression of British colonial culpability for the historical events that were to shape the nation’s making in fact underscores the nation (in De Voortrekkers) as white, that is, comprised both Boers and British.8 This is what makes its cultural significance for Afrikanerdom in the years that followed its making so ironic. But its making in 1916 and its particular view of history, is best explained by the political ‘moment’ of Union in 1910, where the political and economic interests of Boer and British were conjoined, exclusive of blacks, to ensure an unthreatened white future. Thus the film needs to be seen in the post-Union context, rather than in the context of Boer enmity towards the British, post the South African War (1899–1902). Placed this side of 1910, the Zulus can be seen as replacing the British as enemy and furthermore as a rival ‘nation’. De Voortrekkers expounds a mythologically constructed imaginary of the apparent courage of the voortrekkers in demolishing the superior force of the Zulus. Tied in with the broader mythological ‘work’ surrounding the voortrekkers and their significance for Afrikanerdom, it is not difficult to see how the film found its place as cultural icon for the celebration of the Afrikaner ‘nation’.

Beyond these observations Gaines makes a compelling argument for a ‘new interpretation’ of Flora Cameron as victim in The Birth of a Nation, which she links to an analysis of the construction of Afrikaner identity in De Voortrekkers by Gustav Preller, writer of the screenplay. Supplementary to the emphasis on Flora’s ‘rape’ (which is implied in the film and not shown), and which inevitably foregrounds the question of race, Gaines approaches the debate from an embodied perspective tied into the menarche, the moment of first menstruation often historically linked with the first sex act.9 Thus, the rag, the Confederate flag that Flora has had tied around her waist, with which her brother Ben (Henry Walthall) wipes the blood from her mouth, can be seen as standing in for a menstrual rag. Later he holds the same rag high as a symbol of ‘an outraged civilisation’, in the words of the inter-title. This ‘blood mythology’ is the pin around which Gaines’ complex argument turns. As Gaines explains, Dixon’s memoirs signal, retrospectively, the workings of his imagination for the writing of The Clansman. His racism parallels the excess of his mother’s menstrual story, where she is married at 13 prior to the commencement of menstruation (Gaines 2000: 308). Similarly, Preller’s writings in the late 1930s retrospectively signal the basis for his interpretation of Zulu cruelty in the screenplay for De Voortrekkers.

Gaines takes an historical step back to the conception of Shaka, Zulu king before Dingane, and the story of how Nandi, his mother, became pregnant through ‘illicit coupling’ with his father. The elders assigned the cause for the menstrual interruption to iShaka, the intestinal beetle, usually held responsible for menstrual problems (Gaines 2000: 309), hence the name of the new king. In Day-Dawn in South Africa (1938), Preller draws on the Shaka story and ‘evidence’ of Shaka’s cruelty. De Voortrekkers, suggests Gaines, gives us an inkling into the ways in which Preller incorporated myths of Zulu cruelty (2000: 310). As we shall see, Dingane’s cruelty is extended to infanticide, including the murder of his own son. The broader focus of Gaines’ ‘embodied’ perspective is the relations between this and the excesses of racism that the two films invoke, that is, the fevered pitch of reactions to Gus following Flora’s ‘rape’, and the attack against, and final assassination of, Dingane. While The Birth of a Nation broke box-office records in the USA when it was released in 1915 and again on its re-release in 1921, despite protests against it and its censoring, its ideological use was limited. This is where the two films differ, because, as we have seen, De Voortrekkers was used uniquely for the advancement and celebration of nationalist sentiments in the Afrikaner ‘community’ far beyond its release in 1916.

There is a final set of comments to be made based on Gaines’ analysis, tying it to the significance of ‘the body’ and in turn to ‘the nation’. One of the more compelling aspects of her focus on an embodied ‘blood mythology’, is that both films secure the explicitly white future by embodying the birth of the nation within the nuclear family, as evidenced by the child on the mother’s lap at the end of De Voortrekkers. This positions the female body as the ‘harbinger’ of the nation itself and relates to what Susan Hayward calls ‘the symbolic value of the female body’ in nationalist discourse (2000b: 99). Alongside this, the image of the black servant Sobuza seated outside the church, acts as a reference point for a ‘nation’ that is very specifically and exclusively positioned. The very fact of Sobuza’s place on the outside, marginalized from centre stage, couples white identity with black identity in a very particular way. Without Sobuza’s position as servant, the white ‘nation’ and its hegemony cannot survive. The maintenance of that ‘binding’ between black and white identities in history, so sharply evidenced in the ending of De Voortrekkers, was the basis for all the strife that colonialism and apartheid wrought in South Africa.

Isadore William Schlesinger and African Film Productions

I will now extend these contextual reflections by discussing the production context of De Voortrekkers in relation to AFP and I.W. Schlesinger, its founder and owner. AFP was part of the plethora of companies that Schlesinger established and controlled, and that for a long time had virtual monopoly over the production, dis...