Chapter 1

Introduction: The use of animal cell culture

1.

Tissue culture, organ culture and cell culture

Cells, removed from animal tissue or whole animals, will continue to grow if supplied with nutrients and growth factors. This process is called cell culture. It occurs in vitro (‘in glass’) as opposed to in vivo (‘in life'). The culture process allows single cells to act as independent units much like any microorganism such as bacteria or fungi. The cells are capable of division by mitosis and the cell population can continue growth until limited by some parameter such as nutrient depletion.

Animal cells selected for culture are maintained as independent units. Cultures normally contain cells of one type (e.g. fibroblasts). The cells in the culture may be genetically identical (homogeneous population) or may show some genetic variation (heterogeneous population). A homogeneous population of cells derived from a single parental cell is called a clone. Therefore all cells within a clonal population are genetically identical. Cell culture is a widely used technique and is the main subject of this book.

Cell culture is quite different from organ culture. Organ culture means the maintenance of whole organs or fragments of tissue with the retention of a balanced relationship between the associated cell types as exists in vivo. This idea of the maintenance of tissue was important in the early development of culture techniques. However, it was soon realized that this was extremely difficult over long periods because of the differing growth potential of individual cell types within a tissue.

Nowadays the culture of individual cells is the preferred technique because conditions can be controlled to allow some degree of consistency and reproducibility in cell growth. Although ‘cell culture’ is the most appro priate and logical term for this, it is still widely referred to as ‘tissue culture’ - a term that can be misleading, as it is also used to refer to organ culture.

2.

Why grow animal cells in culture?

There are a number of applications for animal cell cultures:

- to investigate the normal physiology or biochemistry of cells. For example, metabolic pathways can be investigated by applying radioactively labeled substrates and subsequently looking at products;

- to test the effects of compounds on specific cell types. Such compounds may be metabolites, hormones or growth factors. Similarly, potentially toxic or mutagenic compounds may be evaluated in cell culture;

- to produce artificial tissue by combining specific cell types in sequence. This has considerable potential for production of artificial skin for use in treatment of burns.

- to synthesize valuable products (biologicals) from large-scale cell cultures. The biologicals encompass a broad range of cell products and include specific proteins or viruses that require animal cells for propagation. The number of such commercially valuable biologicals has increased rapidly over the last decade and has led to the present widespread interest in animal cell technology. Proteins that are present in minute quantities in vivo can be synthesized in gram (or kilogram) quantities by growing genetically engineered cells in vitro.

3.

The advantages and disadvantages of using cell culture

In all the situations listed above we could use animal tissue (e.g. liver) or whole animals (e.g. mice). Biochemists have traditionally used homogenized liver as a source of cells for enzyme or metabolic studies. So, why use animal cell culture which may require far more time in preparation and may require specialized equipment?

The major advantage to using cell culture is the consistency and reproducibility of results that can be obtained by using a batch of cells of a single type and preferably a homogeneous population (clonal). For example, we may be doing a biochemical analysis where it is important to relate a particular metabolic pathway to a certain cell type. This would be possible in a culture containing a homogeneous cell population which can be monitored for biochemical and genetic characteristics, but very difficult in a tissue homogenate which would contain a heterogeneous mix of cells at different stages of growth and viability.

Toxicological testing procedures have been well established in laboratory animals. However, the use of cell culture techniques may allow a greater understanding of the effects of a particular compound on a specific cell type such as liver cells (hepatocytes). Furthermore, routine toxicity tests are far less expensive in cell culture than in whole animals.

In the production of biological products on a large scale, the avoidance of contaminants such as unwanted viruses or proteins is important. This can be more easily performed in a well-characterized cell culture than when dealing with pooled animal tissue.

The major disadvantage to the use of cell culture is that after a period of continuous growth, cell characteristics can change and may be quite different from those originally found in the donor animal. Cells can adapt to different nutrients. This adaptation involves changes in intracellular enzyme activities. Furthermore, culturing favors the survival of fast-growing cells which are selectively retained in a mixed cell population.

The changes in the growth and biochemical characteristics of a cell population may be a particular problem when using cultures to develop an understanding of the behavior of cells in vivo. After a period of culture, the cells may be significantly different from those that are highly differentiated in vivo where growth has ceased. Intracellular enzymeactivities change dramatically in response to nutrient depletion and by-product accumulation in a culture.

Some of the characteristics of cells in culture are discussed further in Chapter 2.

4.

The early history of cell culture

The techniques necessary to allow animal cells to grow in culture were gradually developed over the course of the last century (see Table 1.1). The original impetus for the development of cell culture was to study, under a microscope, normal physiological events such as nerve development.

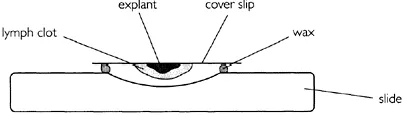

One of the earliest experiments showing cell culture in vitro was conducted by Ross Harrison in 1907 who developed the ‘hanging drop’ technique which is illustrated in Figure 1.1. In the depression of a microscope slide he entrapped small pieces of frog embryo tissue in clotted lymph fluid (Harrison, 1907). By this method he was able to observe the elongation of nerve fibers over several weeks.

From his experiments he demonstrated some of the characteristics and requirements for the maintenance of cells.

Table 1.1. Milestones in the development of animal cell technology

Figure 1.1 Hanging drop technique of cell culture.

- The cells require an anchor for support which in this case was provided by the coverslip and the fibrous matrix of the lymph clot. Cells that are bound to a tissue matrix in vivo are normally anchorage-dependent when grown in culture. Several proteins are responsible for glueing the cells to a solid surface. The best characterized is fibronectin.

- The cells require nutrients which are provided by the biological fluid contained in the clot.

- The growth rate is relatively slow (compared to bacteria) and this makes the culture vulnerable to contamination. A small number of bacteria would soon outgrow a larger population of animal cells. The doubling time for animal cells is normally between 18 and 24 hours but bacterial cells can double in 30 minutes.

Some of these early culture experiments were continued by Alexis Carrel who was trained as a surgeon (Carrel, 1912). He showed that the application of strict aseptic control enabled the prolonged subculture of the cells. He used chick embryo extracts mixed with blood plasma to support cell growth. In 1923 Carrel designed a flask suitable for routine cell culture work (Figure 1.2). This facilitated subculture under aseptic conditions and was the forerunner of the modern cell culture flask. Sterile manipulation is facilitated by the narrow-angled glass neck of the Carrel flask which can be flamed by a Bunsen burner prior to inoculation or sampling.

However, Carrel’s application of surgical procedures for aseptic manipulation of cell cultures was elaborate and difficult to repeat by others. Consequently cell culture was not adopted as a routine laboratory technique until much later (reviewed by Witkowski, 1979). Of course, today cell culture is widely used and can be performed in most moderately equipped laboratories.

Figure 1.2 The Carrel flask.

Carrel is particularly well known for his 34-year culture experiment. In 1912 he isolated a population of chick embryo fibroblasts and these cells were grown in culture until 1946. From this, Carrel concluded that the cells were immortal. However, this claim was later refuted by the work of Hayflick and Moorhead who showed the finite lifespan of isolated animal cells (see below). It is now thought that Carrel’s technique of using plasma and homogenized tissue as growth medium most likely allowed continuous reinoculation of cells into his culture.

5.

How long will primary cultures survive?

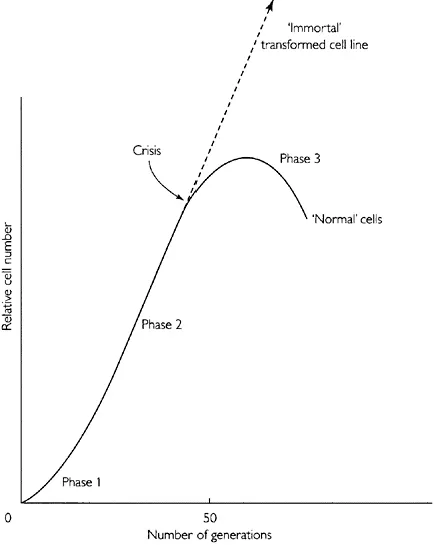

In 1961, Hayflick and Moorhead studied the growth potential of human embryonic cells. They showed that these cells could be grown continuously through repeated subculture for about 50 generations (Hayflick and Moorhead, 1961). After this time, the cells enter a senescent phase and are incapable of further growth. Figure 1.3 illustrates the pattern of growth during the lifespan of these cells.

Figure 1.3 Normal and transformed growth of human embryonic cells over an extended number of passages.

A finite growth capacity is a characteristic of all cells derived from normal animal tissue. The cells appear to pass through a series of age-related changes until the final stage when the cells are incapable of dividing further. The finite number of generations of growth is a characteristic of the cell type, age and species of origin and is referred to as the ‘Hayflick limit’.

The capacity for growth is related to the origin of the cells—those derived from embryonic tissue have a greater growth capacity than those derived from adult tissue. Each cell appears to have an inherent ‘biological clockŒ defined by the number of divisions from the original stem cell. Even if cells are stored by cryopreservation the total capacity for cell division is not altered.

6.

The biological clock

The molecular mechanism that limits the growth capacity of normal cells was a mystery for a number of years until some key observations were made regarding chromosomal length. In 1986 Howard Cooke made the observation that the caps at the end of chromosomes of human germline cells were longer than somatic cells (Cooke and Smith, 1986). These caps known as telomeres are repeats of the nucleotide sequence TTAGGG/CCCTAA and are shortened at each generation of growth of somatic cells. This is not surprising given the semiconservative mechanism of DNA replication which operates in one direction (5Πto 3' end). This generates a fork of replication that cannot work at the end of double-stranded DNA. Therefore, at each mitotic division there is a small segment of DNA that is not replicated, thus shortening the telomeric cap.

However, in germ cells the telomere is maintained at 15 kilobases apparent...