![]()

Part One

Scoping Complexity

![]()

Chapter 1

Postindustrial Emergence

This chapter covers four precepts that are fundamental to the emerging traits of postindustrial architecture. The backgrounds may be familiar in various degrees to some readers, but the connections among these precepts will situate Two Spheres as the affective and effective aspects of architecture; referred to here respectively as physical and strategic design elements.

The first precept describes three epochs of history as a developmental trace of industrialization, technical progress, and social good. This historical perspective is then tied to some of the key conflicts in architectural thought that were brought about by postindustrial change. Louis Kahn’s aphorism on the measurable and immeasurable aspects of great buildings illustrates this as a conflict symptomized by two spheres: physical and strategic elements of design. From there, discussion shifts to assertions about wholeness and complexity and their vital role in architecture. Finally, the physical and strategic spheres are detailed as two equal components of designerly thinking. Distinguishing characteristics of the two spheres are laid out; not as simplistic and conflicting definitions, but rather as a systemic and generative dialectic. In sum, Chapter 1 overviews a framework for understanding how physical and strategic elements of architecture operate in tandem, and then lays explanatory groundwork for how their dynamic interplay constitutes whole-minded architecture. Particular details on each of the four precepts are developed throughout.

Precept One: Three Epochs

From 1915 to 1932, Scottish ecologist Patrick Geddes and American historian Lewis Mumford collaboratively framed the story of human civilization as a co-evolving history of technical progress, industrialization, and social good.1 They classified this story into three sequential eras as the eotechnic, paleotechnic, and neotechnic; indicating progressive, overlapping, and interpenetrating evolutions. These eras spanned from a long age of primary production of raw materials by farming and mining, then to a shorter intermediary period of industrial goods production and consumption, and finally to our emerging cybernetic era of innovation and scientific progress. Our current transition from localized myopic and mechanistic industrial age perspectives to more globally holistic and systemic postindustrial attitudes of the neotechnic is especially important in this sequence. As Paleotects, Geddes wrote,

we make it our prime endeavour to dig up coals, to run machinery, to produce cheap cotton, to clothe cheap people, to get up more coals, to run more machinery, and so on, and all this essentially towards “extending markets.”

(Geddes 1915: 74; cited in Renwick & Gunn 2008: 67)2

While Geddes saw the paleotechnic and neotechnic epochs as subdivisions of the industrial era of his own time, he did delineate the paleotechnic from the neotechnic in ways that foresaw the advent of postindustrial society and the ethic of sustainability:

the first [paleotechnic epoch] turning on dissipating energies towards individual money gains, the other [neotechnic] on conserving energies and organising environment towards the maintenance and evolution of life, social and individual, civic and eugenic.

(Geddes 1915: 60)3

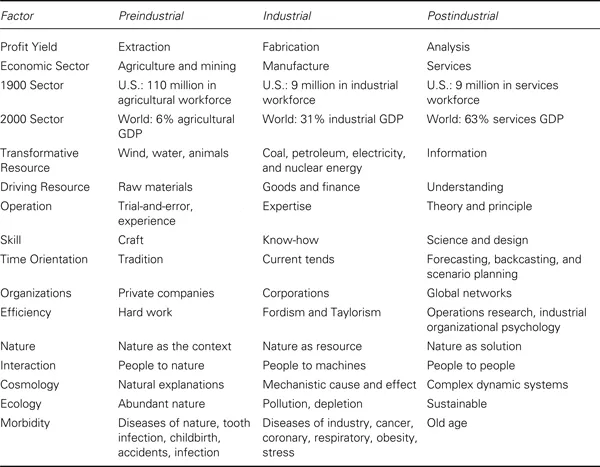

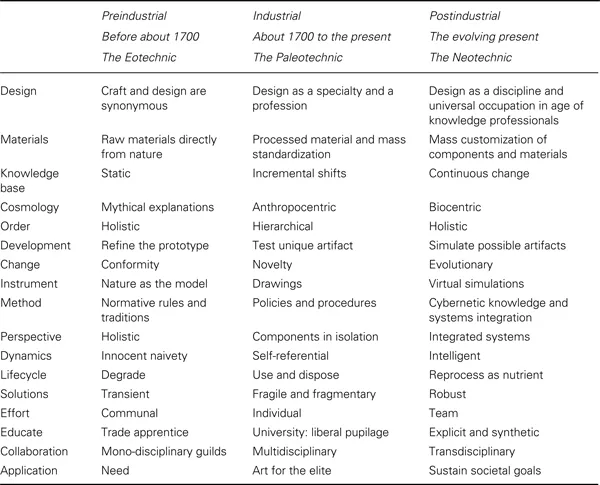

Several decades after Geddes and Mumford, the Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell placed the American transition from an industrial goods basis of production to a primarily postindustrial information society as occurring in the 1950s.4 This passage supposedly marks a point in time when the service economy became larger than the goods economy. The actual economic trends may not quite agree with Bell’s contentions, but it is quite accurate to see postindustrial change as an aspect of the post-World War II emerging information society, and most sociologists now place the transition as occurring in the late 1950s (Table 1.1). More specifically relevant to architecture, this postindustrial transition also signaled a move from linear mechanistic bottom-line thinking to a more human-centered perspective of global networks, complex interdependence, and long-term value.

Table 1.1 Postindustrial society

Sources: Some portions adapted from D. Bell, ‘Welcome to the postindustrial society’, Physics Today, Feb. 1976: 46–49

Parallels of Bell’s work with the techno-social timeline by Geddes and Mumford are illustrated in Table 1.2. More in-depth discussion on this historical framework is offered in Novak (1995), Lyle (1994), and Renwick and Gunn (2008).5 Lyle’s Regenerative Architecture is particularly valuable in depicting the sustainable design ethic of the neotechnic era.

Table 1.2 Tech ne: Ideals and means of production as a story about civilization

Geddes 1915 | Mumford 1934 | Bell 1973 |

EOTECHNIC (life in balance): Geddes apparently did not use this term, but Mumford credits him for its use and meaning | EOTECHNIC, AD 1000 to 1700: Village life, coal and steel, the clock as a model of capitalism and the laudable search for an intensification of life | PREINDUSTRIAL: Agriculture and mining for raw materials as the basis of production |

PALEOTECHNIC (life threatened): Private dispensation of resources for individual gain | PALEOTECHNIC, 1700 to 1900: Industrial cities and the megalopolis, problem solving for profit rather than a search for general principles | INDUSTRIAL: Conversion of raw materials to goods and the continual consumption of those goods, practical know-how dominates, productive labor is primary |

NEOTECHNIC or EUTECHNIC (life resurgent): Public conservation of resources toward future evolution of the public good | NEOTECHNIC, 1900 to about 1934 and forward: Organic human-scale living, electricity and automation free up labor, innovation, science, communication, and information are primary concerns | POSTINDUSTRIAL: Information as currency, data as empirical reality, knowledge as decision making, stochastic forecasting, codification of theoretical knowledge, primacy of human capital, growth of intellectual technology |

The decade of the 1960s then witnessed an inevitable surge of postindustrial thought and social transition. Beyond the highly visual impacts of rustbelt decay and urban blight, these influences were manifested in architecture as a whole new range of influential notions such as design programming, systems theory, ecology, and the influence of postmodern philosophy. As Thomas Kuhn’s theory on The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) suggests would happen, the existing paradigms of architectural design thinking then eroded to the point where they no longer satisfactorily explained architectural events occurring within the new circumstances of postindustrial transformation.6 Consequently, when architects working in the early 1960s were faced with having less robust approaches to their work and less relevant theories to explain their intentions, a separation formed between the modernist paradigm and the pluralistic approaches that emerged in promise of new normative explanations for the neotechnic role of design.

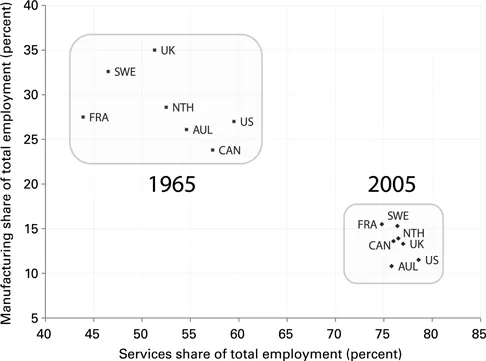

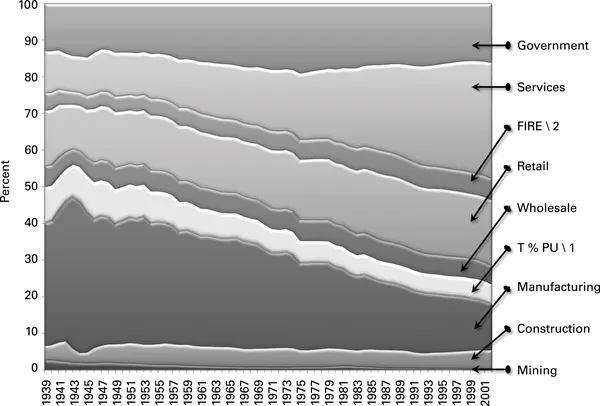

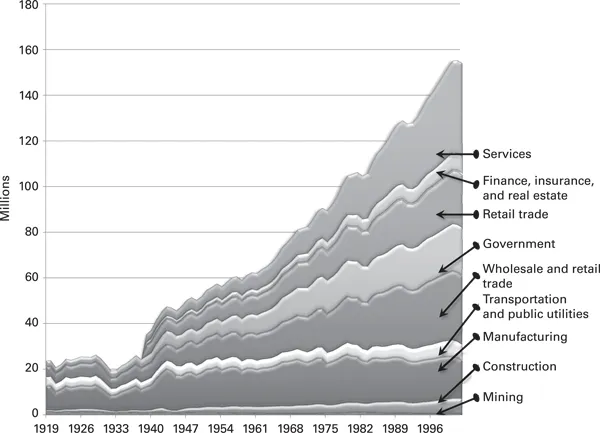

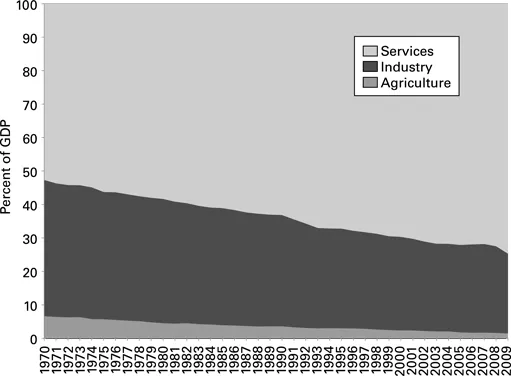

Postindustrial society continues to take form and to reshape architectural practice and design thinking on into the twenty-first century. As context, the 2009 world economy was distributed at about 6 percent farming, 30 percent manufacturing and industrial, and 60 percent service based. A brief statistical overview of world employment distribution and the corresponding gross domestic product (GDP) will illustrate the sweeping and dramatic shifts that are transforming not just the global economy, but also society, culture, and fundamental world perspectives. The numerical references however are only included to illustrate that postindustrial evolution is our core agent of real progress and essential inspiration toward a better world future. This societal context is the systemic, first order, rock-splashes-in-the-water change, after which other issues are symptomatic ripples and secondary after-effects. To be a real and relevant part of this, architecture must become a primary instrument of this transformation and manifest the societal, cultural, and technological mutations within which design operates. Postindustrial architecture is thus presented with one of the most momentous opportunities in the history of human civilization. Figures 1.1 to 1.4 portray some of the social and economic circumstances.

Figure 1.1 Changeinthe share of total employment for manufacturing and service sectors in selected countries. Notes: AUL: Australia, CAN: Canada, FRA: France, NTH: Netherlands, SWE: Sweden, UK: United Kingdom, US: United States. Source: Data from the World Bank.

Figure 1.2 Change in US employment by percentage share of each sector. Notes: 1 T & PU: transportation and public utilities; 2 FIRE: finance, insurance, and real estate.

Figure 1.3 Change in US employment for each sector by headcount.

Figure 1.4 The European Union countries: Combined GDP for each sector of the economy from 1970 to 2009.

Source: Data from the World Bank.

Postindustrial shifts have clearly led us away from goods production and toward information-based production by knowledge workers. As a representative change in thinking, consider the analogy of cooking dinner, which depends both on what is in the pantry, and on how good the recipe is. Industrial age thinking focused primarily on the pantry whereas postindustrial thinking focuses more on the recipe. Recipes of course are just information we can access, select, refine, tailor, and interpret freely, but the better the recipe, the better the dinner, and a really good recipe can apply innovative ideas to readily available and inexpensive ingredients so as to create valuable results. That added value is the basis of postindustrial production and the intelligence coded into the recipe is the strategic design component of how that value is conceptualized, produced, and realized (see Romer, The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics).7 In architecture, that process is observable in the act of design.

Building on the portrayal of three epochs in Tables 1.1 and 1.2, some dimensions of how the strategic sphere of intelligent recipes is pushing architectural design are set out in Table 1.3. The primary thrust is that of holistic, large-scale, inclusive thinking that treats everything and everywhere as an interrelated whole. Left behind are the industrial age failings of fragmentation, isolation, and mechanistic faith in treating the symptom of any problem that might arise rather than dealing with systemic cause and relation.

Table 1.3 Design in the postindustrial era

To use another visual analogy: mechanistic industrial age efforts are like a tree farm, a machine for making trees. Posti...