- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Landscape Planning And Environmental Impact Design

About this book

Written for use in undergraduate and postgraduate planning courses and for those involved in all aspects of the planning process, this comprehensive textbook focuses on environmental impact assessment and design and in particular their impact on planning for the landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Landscape Planning And Environmental Impact Design by Tom Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Landscape Planning

Introduction

To conserve and create a good environment, societies need:

- Information

- Ideals

- Theories of context

- Laws

Chapter 1 discusses the strategic role of information in the planning process.

Chapter 2 reviews the ideals and the plans which may guide us in the conservation and development of fine landscape, as a lighthouse guides ships.

Chapter 3 considers the laws and theories of context which can help fit projects to their environmental niches.

CHAPTER 1

Will planning die?

Specialisation…is the mortal sin

Karl Popper (1945)

Will planning die away, then?

Environmental planning has been too scientific, too man-centred, too pastfixated and two-dimensional. In Cities of tomorrow Peter Hall asks “Will planning die away, then?” (Hall 1988:360). His answer is markedly cautious: “Not entirely”. The thirst for liberalism and economic growth, which pushed back planning in the 1980s and smashed the Berlin Wall, now threatens all types of government planning. But, argues Hall, a core is likely to survive. This is because:

Good environment, as the economists would say, is an income-elastic good: as people, and societies generally, get richer, they demand proportionally ever more of it. And, apart from building private estates with walls around them, the only way they are going to get it is through public action. The fact that people are willing and even anxious to spend more and more of their precious time in defending their own environment, through membership of all kinds of voluntary organisations and through attendance at public inquiries, is testimony to that fact. (Hall 1988:360)

This chapter looks at the factors that have caused our doubts about planning, and at how they might be resolved. The argument, in summary, is that geography created the opportunity for physical planning, that geography revolutionized planning at the start of the twentieth century, and that geography can revolutionize planning once again. A development of profound importance, the computer-based Geographical Information System (GIS), is set fair to be the revolution’s handmaiden. Modern geography and modernist planning are giving way to a future in which there will be a myriad of thematic maps, pluralist plans and non-statutory action by user groups ‘willing and even anxious to spend more and more of their precious time’ on the environment.

A good environment, like good health, is easy to recognize but hard to define. And “health is not valued till sickness comes”. To conserve and improve our health, doctors must understand the workings of the body. To conserve and improve our environment, planners must understand the geographical equivalents of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry. Doctors found it easier to investigate surface anatomy than the interior. Planners found it easier to investigate the physical environment than its workings. But one cannot treat the inside of the body by treating the skin, and one cannot improve the environment by dealing only with the visible. Knowledge, ideas, beliefs and skills are required.

Gender and planning

Planning has been “too masculine”: it has concentrated on the way of the hunter and neglected the way of the nester.

Abstract thought characterizes the way of the hunter and, hitherto, the way of the planner. Hunters identify a goal, formulate a plan and decide upon a course of action. In most human societies, this has been a masculine role (Betsky 1995). It requires dominance and it has led societies to privilege the way of the hunter over the way of the nester. In this sense, planning has been too masculine and too preoccupied with a never-present future. In times of scarcity, hunting may take precedence over other activities. In times of plenty, the nester can give thought to the long-term wellbeing of the species, while the hunter continues to sacrifice everything for a single objective. Modern planning has over-emphasized both man-the-hunter and man-the-species.

In the 1780s Lord Kames, an important figure in the history of aesthetic philosophy, wished to “improve” Kincardine Moss for agriculture. He therefore diverted a river and washed so much peat into the Firth of Forth that the estuarine shore was made brown and sticky for a decade. Standards have changed. Such a policy would now be judged unethical and illegal. There was an international outcry when the wreck of the Exxon Valdez washed an oil slick onto the pristine shore of Prince William’s Sound in the 1980s. Aldo Leopold compares the advent of a land ethic to the changed relationship between the sexes:

When the God-like Odysseus returned from the wars in Troy, he hanged all on one rope a dozen slave-girls of his household whom he suspected of misbehaviour during his absence. (Leopold 1970)

They were his property—to be disposed of as he wished. Ethical standards now embrace relations between man and environment. To the regret of some, land can no longer be treated as a woman or a slave, to be raped and destroyed at will. The creation of a good environment requires the way of the hunter to be fused with the way of the nester. Planning needs to be less dictatorial and more inspirational.

Science and planning

Planning has been “too scientific” in the sense of trying to project trends and deduce policies from empirical studies of what exists.

It is right that diagnosis should come before treatment, but prescriptive plans cannot be derived from scientific studies of what exists. David Hume, the empiricist philosopher, declared that ought cannot be derived from is. His subject was morality. His point has continuing importance for planning:

In every system of morality which I have hitherto met with I have always remarked that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find that, instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. The change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. (Hume 1974 edn, III(i): 1)

Take the case of highway planning. Surveys will show the trend in vehicle movements to be rising. Analysis of origins and destinations will show where vehicles come from and whither they are bound. Alternative alignments for new roads can be mapped. Public consultation takes place. The best route is chosen. The road should be built on this alignment. Money will be allocated next year. By imperceptible degrees, highway planners develop the case for new roads. If this mode of reasoning is accepted, similar studies will go on leading to similar conclusions, until all the cities in all the world are blacktop deserts with isolated buildings surrounded by cars—standing as bleak monuments to the folly of pseudo-scientific planning.

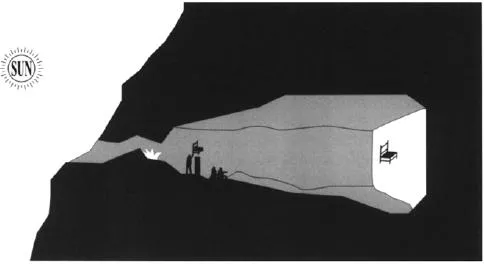

Science is characterized by the application of reason and observation. They are matchless tools, but of limited efficacy. Plato’s analogy of The Cave dealt with the limits to human knowledge and understanding. Men, he suggested, are like prisoners in a cave, able to look only at shadows on the wall, never at the objects that cast the shadows (Fig. 1.1) Nor is modern science able to reach beyond the walls of the cave, although our cave is larger. In the absence of certain knowledge as to why the human race exists and how its members ought to behave, it is necessary to rely on judgement and belief. Can science, for example, advise on whether it is right to let a species of animal, say the tsetse fly, become extinct?

Figure 1.1 Plato’s Cave Analogy suggests that we live as prisoners, chained in an underground cave, only seeing shadows cast on the cave wall.

Our descendants may come to see the twentieth century as the Age of Science. It opened with widespread confidence in the Enlightenment belief that scientific reasoning would usher in a golden age. With ignorance, poverty and disease banished, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse should have been confined to their barracks for evermore. But our confidence was unseated, by two world wars, by some 300 lesser wars between 1945 and 1990, and by a century of environmental despoliation, in which science and technology saddled the Horsemen. Many people now feel that we live in what George Steiner described as Bluebeard’s Castle (Steiner 1971). We keep opening doors to gain knowledge, and in so doing we draw nearer and nearer to that fatal final door which, once opened, will lead to our own destruction. The remedy is not to destroy the Castle of Knowledge. It is to restrain Bluebeard. We must assert the pre-eminence of human values over spurious facts. In planning, rationality must be guided by morality and imagination.

Lack of imagination has been a significant failing of scientific planning. The UK government’s Chief Planning Inspector wrote that:

In particular, at the regional and strategic level, [planning] has been very tentative. Few regional plans or structure plans examine imaginative options for the future, or try to consider in any meaningful way what life in the twenty-first century will be like. (Shepley 1995)

The plans lack imaginative content.

Geography and planning

Three-dimensional design, and the natural tendency for places to evolve and change, have been comparatively neglected by planners.

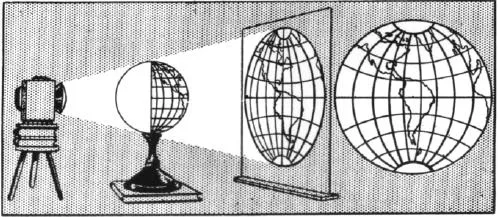

Map-making and planning have ebbed and flowed together. They declined with the Roman Empire and resumed their advance with the Renaissance. Surveying and cartography have a profound influence on geography and planning. Our verb “to plan” derives from the noun “plan”, meaning a two-dimensional projection on a plane surface (Fig. 1.2). The word “geography” comes from geo, meaning “the earth” and graphein, meaning “to write”. Geography is the science that describes the Earth’s surface and explains how it acquired its present character. Before the age of Darwin, Christendom believed the Earth to have been created in six days. Darwin’s theory of evolution changed this belief. When geologists examined the evidence, it was found that the Earth had evolved by infinite degrees on a geological timescale. Ruskin, when he sat to contemplate God and Nature, kept hearing “those terrible hammers” chipping away at the bedrock of his faith.

Figure 1.2 In origin, “to plan” means to make a two-dimensional projection on a plane surface.

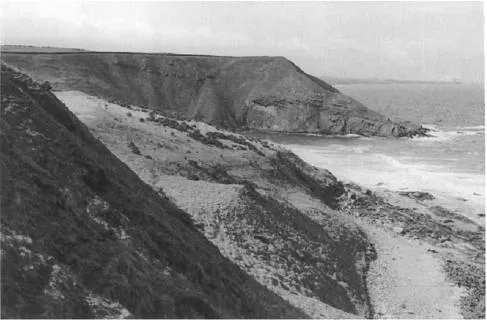

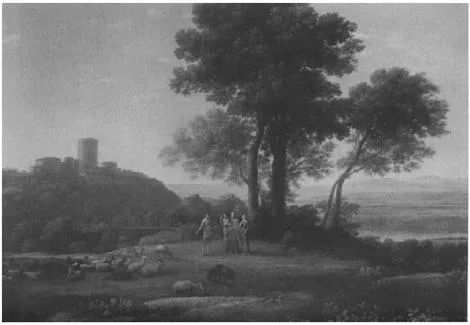

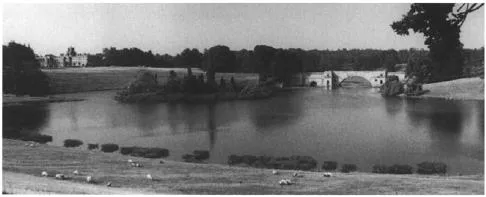

Geikie, a geologist, adopted and adapted the word “landscape” to impart an evolutionary worldview (Fig. 1.3). The Oxford English Dictionary cites one of his books, published in 1886, as the first place in which “landscape” was used in its predominant modern sense: “a tract of land with its distinguishing characteristics and features, esp. considered as a product of shaping processes and agents (usually natural)” (Burchfield 1976). The descriptive use of the word became predominant. Before Geikie, landscape was used in a sense which derived from the Neoplatonic theory of art, to mean “an ideal place”. It was an evaluative word, eminently suited to characterizing a goal of the planning and design process. Landscape painters sought to represent an ideal world on canvas (Fig. 1.4). Landscape designers sought to make landscapes of country estates (Fig. 1.5). However, the evaluative connotations of “landscape” were never entirely discarded: if we speak of a wretched landscape, the phrase has a deliberate internal tension.

Figure 1.3 The geographers’ use of “landscape”—Siccar Point in Berwickshire. Towards the end of the nineteenth century biologists and geographers began to use landscape to mean “a tract of land, considered as a product of shaping processes and agents”. The geological non-conformity at Siccar Point was used, by James Mutton, to prove that the world was made over an immense period of time.

Once the concept of landscape evolution had been grasped, it was natural for planners to look beyond city boundaries. They considered a wide range of geographical phenomena and extended their professional interests beyond the types of plan produced by cartographers, surveyors, architects and engineers. Patrick Geddes, inspired by French geography, was the most influential agent of this change. He had trained as a biologist with Darwin’s collaborator Thomas Huxley. Geddes was also the first British citizen to use “landscape architect” as a professional title. He became a founder member of Britain’s Town Planning Institute and his Survey-Analysis-Plan methodology formalized the link between modern geography and modern planning. The American Institute of Planners was an offshoot of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Figure 1.4 The artists’ use of “landscape”—Claude’s Jacob with Laban and his daughters. Artists used the word landscape to mean “a picture representing natural inland scenery”. Such paintings usually contained buildings and showed men living in harmony with nature. (Courtesy of the Governors of Dulwich Picture Gallery.)

Figure 1.5 The designers’ use of “landscape”—Blenheim Park is one of the great eighteenth-century English landscapes. It was designed, by Lancelot Brown, to be an ideal place where the owner could live in harmony with nature.

Modern planning

Modern planning tended towards the creation of similar places all over the world.

The belief that science, education and planning would inevitably make the world a better place derives from the Enlightenment...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- The Natural and Built Environment series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Part 1: Landscape Planning

- Part 2: Environmental Impact Design

- Appendix: Environmental impact questions

- References