eBook - ePub

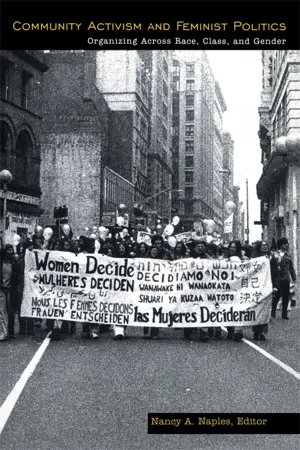

Community Activism and Feminist Politics

Organizing Across Race, Class, and Gender

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This collection demonstrates the diversity of women's struggles against problems such as racism, violence, homophobia, focusing on the complex ways that gender, culture, race-ethnicity and class shape women's political consciousness in the US.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Community Activism and Feminist Politics by Nancy Naples in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Challenging Categories and Frameworks

Chapter 1

Whose Feminism, Whose History?

Reflections on Excavating the History of (the) U.S. Women's Movement(s)

Whose History? Old Perspectives, New Dilemmas

The parentheses in the title of this chapter are less a sign of my infatuation with postmodernist gimmickry than of my own continuing ambivalence about how to “do” the history of feminist activism in the U.S.— what is still conventionally referred to as “the second wave.” Initially annoyed by bell hooks's refusal to use the article—as in “the” women's movement—in one of her earliest works, I now realize that it actually captures my own dilemma (hooks 1984, 26). Referring to women's movements in the plural, on the other hand, reflects a deepening awareness of how the multitudinous forms of women's activism throughout the world all work to challenge patriarchal hierarchies.

Yet, even as we now recognize multiple “feminisms” in contemporary discourse, with few exceptions the histories of their recent manifestations in the U.S. are still largely based on the old hegemonic model.1 Trapped in a time warp, and constrained by our particular historical trajectories and relationships, most US. historians of contemporary feminism still resort to the old litany, describing “the women's movement” as having three (sometimes four) branches variously described as: liberal/reform feminism; socialist/Marxist feminism (a category that at times also includes anarchist-feminism); and radical feminism, which sometimes also encompasses lesbian feminism and sometimes classifies it as a separate branch. Because this model provides such a convenient pedagogical tool, and one that is more manageable than the real complexity of feminist activism based on the intersections of race, class, gender, sexuality, it is reproduced continuously.

Women of color whose feminist activism cannot readily be placed within this paradigm are consequently left out of the histories of the early days of “the women's movement.” Moreover, as Katie King (1994) points out in her far-reaching analysis of some of this literature, even when women of color—particularly African American women—were central players in radical feminist groups, they remain largely unmentioned. To counter the restrictiveness of the three-fold typology and the invisibility it confers upon women of color, at least one Feminist Studies class at Stanford has added a fourth category: “feminism and women of color” (Lee 1995). And while this might be an effective heuristic tactic, it does little to address the basic historiographic problem.

For the most part, the early history of feminist activism among women of color and/or working-class and poor women remains, at best, particular and separate, and does not challenge the accepted paradigm of “second wave” feminism.2 It is only when autonomous groups like the National Black Feminist Organization (1973) and the Combahee River Collective (1977) come out with statements that explicitly ally them with “the women's movement,” that at least some women of color become incorporated into the master narrative.

This veil of silence, particularly with respect to working-class and poor women activists who remained anchored in their local communities, was lifted only after these women became more visible to the larger movement at and following the 1977 National Women's Conference at Houston.3 By 1982, on the heels of difficult political struggles waged by activist scholars of color, groundbreaking essays and anthologies by and about women of color opened a new chapter in U.S. feminism (see especially Moraga and Anzaldúa 1981). The future of the women's movement in the U.S. was reshaped irrevocably by the introduction of the expansive notion of “feminisms.” Nevertheless, this new perspective has not been seriously applied retroactively to re-vision the earlier history.

One of the difficulties in revising the historical narrative and embracing the concept of “feminisms” is the historian's genuine concern about presentism, i.e. projecting contemporary meanings onto the past. Even more problematic is the issue of “ownership,” the deep investment on the part of the participants in the early days of the women's liberation movement in preserving the primacy of our particular experience and analysis (also see King 1994). Not directly faced with race-ethnic or class oppression, the mainly white, middle-class activists—regardless of their analysis of the causes of women's oppression—foregrounded gender. As a result, they assumed both that feminists of color would form autonomous groups and that they would openly criticize the men in their communities. This expectation only widened the chasm and caused many working-class women, poor women, and women of color to distance themselves from “the women's movement,” although they were often pursuing similar goals in the context of their own communities or movement groups.

Because so many of the white, middle-class activists themselves—or their admirers—initially charted the course of feminist history, it is no surprise that their own pasts have shaped how that history has been written. In contrast, women of color and U.S. Third World feminists like Chela Sandoval have challenged the hegemony of “white feminism” and forwarded more plural and differentiated “feminisms” (Sandoval 1982). However, what is often counterposed is a model that implies a unified movement among feminists of color—the result, perhaps, of a homogenization assumed by white feminists (Sandoval 1982; Alarcon 1990). Furthermore, because this vision evolved and was elaborated by members of a cultural and literary elite, the implications of class have not been well integrated into this emergent discourse. In contrast, the hallmark of so much of the activism of working-class and poor women has not been their articulated gender or race or class analyses, but rather their activities growing out of immediate needs. These have been referred to by some as practical gender interests, and in the Latin American context their expression has been dubbed “popular feminism” (Molyneux 1985; Jaquette 1994).

By and large, this kind of neighborhood-based organizing of women in the U.S. has been ignored by feminist historians, except for the discussions of housewives organizing in the Depression years, largely under the aegis of the Community party organizers (Orleck 1993). On the other hand, there is a growing body of feminist sociological studies that document this kind of activism.4 However, this work is usually focused on individual case studies, and is often produced within the framework of social movement theory. The broader implications for a re-visioning of U.S. women's feminist activism have not been fully explored.

The issues raised by the community activism of women place in sharp focus one of the major dilemmas facing any historian who wishes to rewrite the history of contemporary feminism. Focusing on groups whose activities are based on an analysis of women's subordination— what has been referred to by Molyneux as strategic gender interests—seems merely to reinforce the old hegemonic model and discourse. Alternatively, widening our lens to include the kind of community organizing that is the hallmark of working-class and poor women's activism can reduce the idea of feminism to mean simply the empowerment of women.

In an attempt not to focus only on groups driven by a gender analysis or, alternatively, merely to equate feminism with any activity that empowers women, regardless of its intent, the California State University Long Beach, Feminist Oral History Collective (a.k.a. “De-Centerers” ) developed the following working definition of feminist activism:5

Women's groups (including formal and informal committees, subcommittees and caucuses) organized for change whose agendas AND/OR actions challenge women's subordinate [or disadvantaged] status in the society at large (external) and in their own community (internal).

The definitional process was not itself uncomplicated and the oral histories we were conducting with a range of activists were used to evaluate its usefulness and to guard against it being either too broad or too narrow. The question of intended and unintended effects remains somewhat ambiguous, but a distinction can be drawn. For example, a group dedicated to promoting women's education as a way to empower them would fall within this net. But a group whose members are individually empowered by virtue of organizing, e.g. to close down a neighborhood toxic-waste dump, might not—unless they were also challenging the gendered basis of the decision-making process or began to confront the gendered hierarchy within their community as they organized.

As complicated as the question of intent is when the focus is on working-class community activism, it is even more confusing when it comes to deciding how and where lesbian activism fits. Like most women's liberation groups, lesbian feminists were part of a constructed social community, not a spatial or ethnic community. They are usually considered in the master historical narrative of “the” women's movement to the extent that these groups often spun off from radical feminist groups. But where does a group like the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), founded in 1955, belong? Although many of its early members depict the group as serving mainly a social function (Gittings 1976), was their gender-bending nevertheless a challenge to women's subordinate status? If so, the conventional periodization of “second wave” feminism is further undermined, and a new twist is added to the dual question, whose feminism, whose history?

New Perspectives, New Dilemmas

In 1963, at the same time that women professionals were convening the President's Commission on the Status of Women in Washington, DC, a handful of Black women in Watts (Los Angeles) met to found the first grassroots welfare-mothers organization, ANC Mothers Anonymous (named for the Aid to Needy Children program under which they received assistance). In 1968, radical feminists from New York tossed their bras into the trash bins outside the convention hall of the Miss America pageant—a piece of guerilla theater that became mythologized as bra-burning. At the same time, a group of women students in Long Beach, California, were laying the foundation for one of the first modern-day Chicana femenista groups and newspapers, Hijas de Cuauhtemoc. In 1970, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of woman's suffrage, one hundred thousand women marched in New York. That same year, American Indian women (who did not win suffrage until 1924) met to form the North American Indian Women's Association. And, in 1972, when Ms. magazine was launched, Asian American feminists in Los Angeles were already working on the second special women's issue of the radical Asian American community magazine, Guidra.

While the actions of the mainly white women's groups have become major historical markers, the actions of these women of color and poor women in the American west have been little more than footnotes. The study, and particularly the oral histories, of women from the ANC Mothers Anonymous, Hijas de Cuauhtemoc, and Asian Sisters, and of those involved in American Indian women's organizing, adds not just the dimension of race and class, but also a sorely needed western regional perspective.6 As Ellen DuBois and Vicki Ruiz (1990, xii) so eloquently point out, looking to the west provides an important corrective:

For the possibilities of a richer palette for painting women's history, we turn to the “west” … if only because grappling with race at all requires a framework that has more than two positions. Nor is white history always center stage. Even the term “the west” only reflects one of several historical perspectives: the Anglo “west” is also the Mexican “north,” and the Native American “homeland,” and the Asian “east.”

Moreover, Asian American and Chicano activism had their origins in the west in the 1960s. The feminist activism of women in these groups actually predated that of east-coast groups, which are the ones usually cited (see, e.g.. Chow 1987; F Davis 1991). Indeed, the birth of the westcoast Chicana and Asian American women's groups was contemporaneous with the east-coast white women's liberation groups that are at the center of the master historical narrative. Like them, the groups that poor women, Chicanas, and Asians formed in the west were significant beyond their initial, small numbers.

Some of these groups embraced the feminist label, while others elaborated their own versions; and some of the activists openly challenged the sexism of the men in their communities, while others were more oblique in their approach. Regardless of these differences, all drew on their daily life experiences and their political organizing, and were oftentimes attracted to feminist ideas by the contradiction between the liberation discourse of their movements and their practices. They pursued agendas that were designed to mobilize the women in their own communities (national/ethnic, if not necessarily local) and to redress the ways in which sexism, racism, and class domination disadvantaged them in the larger society. Most sought the sources of their strength in their own histories and heroines.

An exploration of the similarities and differences among these groups challenges the conventional history of feminist activism, even as it also reveals some similarities with the experiences of the white feminists. It also challenges what is sometimes presented as a unitary notion of “Third World feminism.” Such an exploration is not unproblematic, furthermore, because it must rely so heavily on oral histories, and thus poses serious intellectual and ethical dilemmas revolving around the issue of interpretive authority For example, to what extent can the consciousness and experience of individual key activists be used to construct the meaning of a group's agenda, particularly when written documentary sources are either missing or minimal? Even more critically, what are the implications of incorporating into a re-visioned history of the women's movement individuals and groups who eschewed the feminist label because of its implications of skin and class privilege? In other words, does an attempt to be inclusive by imposing our 1990s historical sensibility in fact subvert their politics?

These are some of the questions to which I will return after reviewing the history and work of poor women in Watts who became involved in the ANC Mothers Anonymous, the Asian American women activists who formed a host of women's groups within the context of the Asian American movement in Los Angeles, the Chicanas who began to formulate their own gender politics in groups like the Long Beach-based Hijas de Cuauhtemoc, and the American Indian women who came together in the west to forge a common bond of sisterhood and address their issues as native women.

This chapter, strictly speaking, is not a collective product. It is, however, the product of a collective process and represents an ongoing dialogue among us that began in a women's oral history seminar, Spring 1991. The following section draws on my own research as well as that of the three named collaborators, including their oral history projects. Maylei Blackwell conducted interviews with members of Hijas de Cuauhtemoc, Karen harper with activists in the L.A. Asian American Women's Movement; Sharon Cotrell with American Indian activists.7 The material on the various groups discussed here also draws heavily on the research that we each did and the papers we separately produced and/or presented. And while the discussion of each of these groups is drawn from our individual research projects, the framework for the discussion is a result of our earlier collective process and our ongoing conversation.

Origins, Roots, and Traditions

The Black civil rights movement of the 1960s, so often cited as one of the major sources for the emergence of the women's liberation movement in the later part of the decade, also had a profound impact on students and youth in the Asian and Mexican communities. In contrast, the poor women's movement that took hold in local communities in many cities in the early 1960s had little connection to the civil rights movement. Groups like the ANC Mothers Anonymous of Watts (whose anonymity could not be maintained after they appeared on Alan Lomax's radio program in Los Angeles) predated the formal organizing by the male founders of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO). These groups developed out of the immediate survival needs ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- PERSPECTIVES ON GENDER

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgment

- Introduction Women's Community Activism and Feminist Activist Research

- Part I Challenging Categories and Frameworks

- Part II Transforming Politics

- Part III Networking for Change

- Part IV Constructing Community

- References

- Permissions

- Contributors

- Index