Chapter 1

The human unconscious: the development of the right brain and its role in early emotional life

Allan N.Schore

Over the past few years a rapidly growing number of psychological and biological disciplines have been converging on the centrality of emotional processes in human development. Indeed these interdisciplinary studies are elucidating some of the fundamental psychobiological mechanisms that underlie the process of development itself. Contemporary developmental psychology, through attachment theory, is now focusing on the early ontogeny of adaptive socio-emotional functions in the first years of life. In current thinking development is ‘transactional’, and is represented as a continuing dialectic between the maturing organism and the changing environment. This dialectic is embedded in the infant-maternal relationship, and affect is what is transacted in these interactions. This very efficient system of emotional exchanges is entirely non-verbal, and it continues throughout life as the intuitively felt affective communications that occur within intimate relationships. Human development cannot be understood apart from this affecttransacting relationship. Indeed, it now appears that the development of the capacity to experience, communicate, and regulate emotions may be the key event of human infancy.

At the same time, developmental neurobiology is currently exploring the brain structures involved in the processing of socio-emotional information. Indeed, it is now held that ‘the best description of development may come from a careful appreciation of the brain’s own self-organizing operations’ (Cicchetti and Tucker 1994:544). There is widespread agreement that the brain is a self-organizing system, but there is perhaps less of an appreciation of the fact that ‘the selforganization of the developing brain occurs in the context of a relationship with another self, another brain’ (Schore 1996:60). This relationship is between the infant’ s developing brain and the social environment, and is mediated by affective communications and psychobiological transactions. Indeed, neurobiology now refers to ‘the social construction of the human brain’.

Recent models that integrate psychological and biological perspectives view the organization of brain systems as a product of interaction between (a) genetically coded programs for the formation of structures and connections among structures and (b) environmental influence (Fox et al. 1994). Influences from the social environment are imprinted into the biological structures that are maturing during the early brain growth spurt, and therefore have long-enduring psychological effects. The human brain growth spurt, which begins in the last trimester and is at least five-sixths postnatal, continues to about 18–24 months of age (Dobbing and Sands 1973).

Furthermore, DNA production in the cortex increases dramatically over the course of the first year and interactive experiences directly impact genetic sy stems that program brain growth (see Schore 1994; 2001a, b). We now know that the genetic specification of neuronal structure is not sufficient for an optimally functional nervous system—the changing social environment also powerfully affects the structure of the brain. This conception fits perfectly with Anna Freud’s (1965) conception that psychic structure results from successive interactions between the infant’s biologically and genetically determined maturational sequences on the one hand, and experiential and environmental influences on the other.

Thus, very current models hold that development represents an experiential shaping of genetic potential, and that genetically programmed ‘innate’ structural systems require particular forms of environmental input. According to Cicchetti and Tucker:

The traditional assumption was that the environment determines only the psychological residuals of development, such as memories and habits, while brain anatomy matures on its fixed ontogenetic calendar. Environmental experience is now recognized to be critical to the differentiation of brain tissue itself. Nature’s potential can be realized only as it is enabled by nurture

(Cicchetti and Tucker 1994:538).

Sander poses the central question, ‘To what extent can the genetic potentials of an infant brain be augmented or optimized through the experiences and activities of the infant within its own particular caregiving environment?’ (Sander 2000:8). It has even been suggested that, ‘within limits, during normal development a biologically different brain may be formed given the mutual influence of maturation of the infant’s nervous system and the mothering repertory of the caregiver’ (Connelly and Prechtl, 1981:212). This critical ‘mothering repertory’ is expressed in her affect-regulating functions in a co-created attachment relationship with her infant. The development of the child’s attachment outcome is thus a product of the child’s genetically encoded biological (temperamental) predisposition and the particular caregiver affective-relational environment.

Indeed, neurobiology has now established that the infant brain ‘is designed to be molded by the environment it encounters’ (Thomas et al. 1997:209). Recent psychoneurobiological conceptions of emotional development thus model how early socio-emotional experiences influence the maturation of biological structure, which in turn organizes more complex emergent function. This integrative perspective is expressed in the concept of the ‘experience-dependent’ maturation. The experiences required for the experience-dependent maturation of the systems that regulate brain organization in the first 2 years of life are specifically the social-emotional communications embedded in the affect-regulating attachment relationship between the infant and the mother.

The product of this growth-facilitating environment is the emergence of more complex affect-regulatory capacities and a shift from external to internal regulation. Thus, ‘emotion is initially regulated by others, but over the course of early development it becomes increasingly self-regulated as a result of neurophysiological development’ (Thompson 1990:371). A large body of experimental and clinical work now indicates that the maturation of affects and the emergence of more complex communications represent essential goals of the first years of human life, and that the attainment of the essential adaptive capacity for the selfregulation of affect is a major developmental achievement.

Even more specifically, in a number of contributions I cite current findings in neuroscience which suggest that affect-regulating attachment experiences specifically influence the experience-dependent maturation of early developing regulatory systemsof the right brain (Schore, 1994, 1996, 1997a, 1998d, 1999b, 1999d, 2000b, d, 2001a, b, c, d, e, in press a, b, c, d). These early interpersonal affective experiences have a critical effect on, as Bowlby (1969) speculated, the early organization of the limbic system, the brain areas specialized not only for the processing of emotion but also for the organization of new learning and the capacity to adapt to a rapidly changing environment (Mesulam 1998). The limbic system is expanded in the non-verbal right hemisphere, which is centrally involved in the processing of the physiological and cognitive components of emotions without conscious awareness and in emotional communications (Blonder et al. 1991; Spence et al. 1996; Wexler et al. 1992). It is now thought that “while the left hemisphere mediates most linguistic behaviors, the right hemisphere is important for broader aspects of communication’ (Van Lancker and Cummings 1999:95).

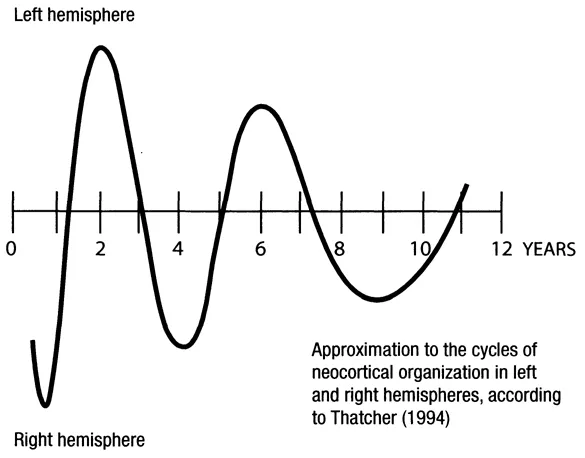

The right hemisphere is in a growth spurt in the first year-and-a-half (see Figure 1.1 ) and dominant for the first 3 (Chiron et al. 1997). A very recent MRI study of infants reports that the volume of the brain increases rapidly during the first 2 years, that normal adult appearance is seen at 2 years and all major fiber tracts can be identified by age 3, and that infants under 2 years show higher right than left hemispheric volumes (Matsuzawa et al., 2001).

For the last 30 years psychoanalysis, the scientific study of the unconscious mind (Brenner 1980), has been interested in the unconscious processes mediated by the right brain, or as Ornstein (1997) calls it, ‘the right mind’ (Schore 1997c, 1999a, d). Recent experimental and clinical studies in developmental psychoanalysis and attachment theory have converged on the centrality of affective functions in the early years of human life, and this body of knowledge has been incorporated into clinical psychoanalysis, which is now ‘anchored in its scientific base in developmental psychology and in the biology of attachment and affects’ (Cooper 1987:83). This advance has been paralleled in the ‘decade of the brain’ by studies in affective and social neuroscience which describe the right lateralized structural systems that mediate the non-conscious socio-emotional functions described by developmental psychoanalysts. Thus I have offered models of how attachment experiences influence right brain maturation (Schore 2000b) and linkages between the self-organization of the right brain and the neurobiology of emotional development (Schore 2000a).

In a number of works I am suggesting that the perspective of developmental neuropsychoanalysis, the study of the early structural development of the human unconscious mind, can make important contributions to a deeper understanding of how early attachment experiences indelibly impact the trajectory of emotional development over the course of the life span (Schore 1994, 1997b, c, 1999a, d, 2000a, b, 2001a, b, c, in press a, b, d). In a recent neuropsychoanalytic contribution I contend that the right brain acts as the neurobiological substrate of Freud’s dynamic unconscious (Schore in press a). Knowledge of how the structural maturation of the right brain is directly influenced by the attachment relationship offers us a chance to more deeply understand not just the contents of the unconscious, but also its origin, dynamics, and structure.

Figure 1.1 Hemispheric brain growth cycles continue asymmetrically throughout childhood, showing early growth spurt of the right hemisphere. (Adapted from Thatcher I994)

The current paradigm shift from cognitive psychology to affective psychology, from purely mental states to states of mind/brain/body, and from the conscious verbal processing of the left verbal brain to the non-conscious processing of the right lateralized emotional brain, is particularly relevant to developmental psychoanalysis. It is now well-established that:

The infant’s initial endowment in interaction with earliest maternal attune ment leads to a basic core which contains directional trends for all later functioning.

(Weil 1985:337)

Current psychoneurobiological models now indicate that the core of unconscious is a psychobiological affective core (Schore 1994).

Writing in the psychoanalytic literature Emde (1983) identifies the primordial central integrating structure of the nascent self to be the emerging ‘affective core’, a conception echoed in the neuroscience literature in Joseph’s (1992) ‘childlike central core’ of the unconscious that is localized in the right brain and limbic system that maintains the self image and all associated emotions, cognitions, and memories that are formed during childhood. I would argue we currently know enough about the development of the right lateralized biological substrate of the human unconscious and that we now must go beyond purely psychological theories of emotional development.

And so in this chapter, I will present an overview of recent psychological studies of the social-emotional development of infants and neurobiological research on the maturation of the early developing right brain. I will focus on the structure-function relationships of an event in early infancy that is central to human emotional development: the organization, in the first year, of an attachment bond of interactively regulated affective communication between the primary caregiver and the infant. These experiences culminate, at the end of the second year, in the maturation of a regulatory system in the right hemisphere. I will then discuss the relationship between continued right brain maturation, more complex emotional development, and the expansion of the unconscious right mind over the life span.

Throughout, keep in mind Winnicott’s dictum that the clinical encounter is always a mutual experience:

In order to use the mutual experience one must have in one’ s bones a theory of the emotional development of the child and the relationship of the child to the environmental factors.

(Winnicott 1971:3)

But also consider Watt’s recent injunction, in the journal Neuropsychoanalysis, regarding the nature of ‘(neuro) development’:

In many ways, this is the great frontier in neuroscience where all of our theories will be subject to the most acid of acid tests. And many of them I suspect will be found wanting… Clearly, affective processes, and specifically the vicissitudes of attachment, are primary drivers in neural development (the very milieu in which development takes place, within which the system cannot develop).

(Watt 2000:191)

Attachment processes as dyadic emotional communications

From birth onwards, the infant mobilizes its expanding coping capacities to interact with the social environment. In the earliest proto-attachment experiences, the infant uses its maturing motor and developing sensory capacities, especially smell, taste, and touch. But by the end of the second month there is a dramatic progression of its social and emotional capacities. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies now demonstrate that a milestone for normal development of the infant brain occurs at about 8 weeks (Yamada et al. 2000). At this point a rapid metabolic change occurs in the primary visual cortex of infants, reflecting the onset of a critical period in which synaptic connections in the occipital cortex are modified by visual experience. The mother’s face is the primary source of visuo-affective information for the developing infant.

It is at this very time that face-to-face interactions, occurring within the primordial experiences of human play, first appear. Such interactions:

emerging at approximately 2 months of age, are highly arousing, affect-laden, short interpersonal events that expose infants to high levels of cognitive and social information. To regulate the high positive arousal, mothers and infants … synchronize the intensity of their affective behavior within lags of split seconds.

(Feldman et al. 1999:223)

These dyadic experiences of ‘affect synchrony’ occur in the first expression of positively charged social play, what Trevarthen (1993) terms ‘primary intersubjectivity’, and at this time they are patterned by an infant-leads-mother-follows sequence. This highly organized dialogue of visual and auditory signals is transacted within milliseconds, and is composed of cyclic oscillations between states of attention and inattention in each partner’s play. In this communicational matrix both synchronously match states and then simultaneously adjust their social attention, stimulation, and accelerating arousal to each other’s responses (see Figure 1.2).

Within episodes of affect synchrony parents engage in intuitive, non-conscious, facial, vocal, and gestural preverbal communications:

[T]hese experiences provide young infants with a large amount of episodes—often around 20 per minute during parent-infant interactions—in which parents make themselves contingent, easily predictable, and manipulatable by the infant.

(Papousek et al. 1991:110)

In such synchronized contexts of ‘mutually attuned selective cueing’, the infant learns to send specific social cues to which the mother has responded, thereby reflecting ‘an anticipatory sense of response of the other to the self, concomitant with an accommodation of the self to the other’ (Bergman, 1999:96). These are critical events, because they represent a fundamental opportunity to practice the interpersonal coordination of biological rhythms. According to Lester, Hoffman, and Brazelton ‘synchrony develops as a consequence of each partner’s learning the rhythmic structure of the other and modifying his or her behavior to fit that structure’ (Lester et al. 1985:24).

Since the mother’s psychobiological attunements to the dynamic changes of the infant’s affective state are expressed in spontaneous non-verbal behaviors, the moment-to-moment expressions of her interactive regulatory functions occur at lev...