eBook - ePub

Ecstasy and the Rise of the Chemical Generation

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecstasy and the Rise of the Chemical Generation

About this book

This book about ecstacy users' lives is based on one of the biggest government-funded projects ever undertaken and gives voice to the chemical generation for the first time. In the UK, where the study was conducted, over fifty per cent of young people use drugs, a quarter of them regularly. The people in this book are ordinary, decent, family-loving people, with normal lives, normal problems and normal aspirations. Through their own words we hear how they first started using ecstasy, how they use it in different ways, why clubbing and raving are so important, how good sex is on ecstasy, how they chill out, how they come down, what problems they encountered and why they quit.

This path-breaking book ends by trying to answer the questions on the lips of every member of the chemical generation: what are the long-term effects of ecstasy? Because we can't answer them, the authors claim, we are failing in our duty to our children: telling them not to take ecstasy is alienating and pointless.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecstasy and the Rise of the Chemical Generation by Jason Ditton,Richard Hammersley,Furzana Khan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction – Getting into Ecstasy

In many ways, Ecstasy is an extraordinary drug. What particularly distinguishes it from everything that came before was the deliberate choice of such an advertiser's dream of a name for the rather less easily pronounceable MDMA (or, to be even more technical, 3–4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine). Rumour even has it that “empathy” was field tested as a candidate name, but that “Ecstasy” had more sales appeal. Furthermore, its apparently curious affect – a mixture of the energetic effects of, say, amphetamines, and the psychedelic effects of, for example, LSD – even meant that a whole new substance class, “entactogens”, had to be coined for experts to find somewhere to place it.

Although it only burst on the British scene in a big way in the early 1990s,4 drifting over, it seems, from the raver's holiday paradise island of Ibiza, it was first patented by the German pharmaceutical giant, Merck, in 1912. Actually, the original patent had been issued on Christmas Eve of that year, and perhaps this is why one of its nicknames is “eve”. Apart from the almost obligatory appearance in the notorious American army drug trials of the 1950s, little was heard of it thereafter until it surfaced as the psychotherapists” drug of choice in California in the late 1960s. They referred to it, incidentally, by another nickname: “adam”.

The American Drug Enforcement Agency succeeded in having it criminalised in 1985, and in the most restrictive category of all. In Britain, too, it is similarly heavily penalised: here as a Class A Dangerous Drug. It could be said that this has not really had the desired effect. Estimates of the extent of use range from 200,000 to 5 million uses per week in Britain, although 1 million weekly uses is a widely accepted benchmark. The media (as we shall see in Chapter Five) paint only a dreary picture of Ecstasy-death on first consumption of an Ecstasy tablet – something which, given even the lowest estimate of the frequency of weekly use, must be a highly unusual event.

What would be a more typical experience of using Ecstasy for the first time? We start with a few experiences from our research subjects, before describing them, and how we recruited them. As we will see, right from the start people report very different experiences on this drug.

“It was magic. All your muscles relax, and you felt this great surge of energy...” (Phil)

“One of the best nights of my life, and I've been sort of hooked on the feeling ever since. I had an amazing night!...the next thing I knew, I was in the middle of the dance floor...in the middle of the dance floor on my own...I just had this uncontrollable urge to dance, and I just spent the rest of the night going “Give me more! Give me more!”...” (Gael)

“I didn't really know exactly how it was supposed to make you feel. I knew it was supposed to make you feel happy, but that's the only thing I knew about it. I never asked. I just took it, and that was that...It didn't make me communicative: I think the opposite. I just felt that I've got thoughts, but I don't want to speak. I was just happy not talking at all...Ecstasy makes you sort of sit there with a big smile on your face, not talking...” (Sandra)

“The first time I ever took it...it didn't work. It was about the 4th or 5th one that I took before it...but to start with, I only took a wee bit. I never took a whole one for a while...” (Agnes)

Who are these people? How did we get them to talk to us?

GETTING THE LARGE SAMPLE TO COMPLETE QUESTIONNAIRES

Finding Ecstasy Users

This book is based mainly on two sources of information. First, we interviewed 229 Glaswegians using a detailed questionnaire. Of this group, which we call the “large sample”, 20 had never used Ecstasy, 8 had quit using Ecstasy, and 201 were still using it. Second, we tape-recorded in-depth qualitative interviews with 22 of these Ecstasy users, and material from these interviews is referred to as coming from the “small group”. Just before we completed the book, we re-interviewed 7 of the 22 again.

People were recruited for the large sample using a now conventional community “snowballing” strategy. Ecstasy users were contacted – the initial criterion for inclusion in the study was that people had taken Ecstasy at least once – in a variety of ways and in a variety of settings. If convinced of our good intentions, and if they knew other Ecstasy users, these initial interviewees often themselves gave us the names and addresses of other people for us to interview.

The emerging demographic profile of the growing sample was monitored regularly, and with greater and greater stringency as the sample grew in size. Starting in December, 1993, everyone available was interviewed in the early stages, beginning with 8 “first contacts” to different potential chains. However, it soon became apparent that – perhaps given the prevalence of Ecstasy use – chains seemed inexhaustible, and that interviews were mostly with experienced poly-drug users in their mid-twenties that, as a group, had a rather middle class skew. These were practically all Ecstasy users, some of them heavy users, but it appeared that they had merely added Ecstasy to the other drugs that they used from time to time.

This is not altogether unusual, as the idealised research search for one-drug users always has to contend with an untidier reality choice between non-drug and poly-drug use. However, a small group of relatively ubiquitous drugs (cannabis, amphetamines, nitrites, LSD and Ecstasy) is believed to be the drug group of choice of those dancing for many hours at “raves”.5 Those in this sample who conformed to this use pattern were termed “predominant Ecstasy users”, although it is recognised that their cannabis (and possibly amphetamine and LSD) use might be more frequent. By the end of March 1994 (and with the completion of 76 interviews), only 37% of the sample could be classified as “predominant Ecstasy users”. (The search for “only Ecstasy users” failed to find a single interviewee).

Accordingly, the recruitment strategy was reviewed at the end of March 1994 (after the first four months' fieldwork). There are no formal scientific techniques for this, because “snowballing” operates in an environment where the nature, type and size of the population being sampled is itself unknown. Jerome Beck and Marsha Rosenbaum in their excellent American study of Ecstasy use,6 faced the same problem in collecting their sample of 100 Ecstasy users, and commented on page 164 of their book:

“We made decisions as to whether a particular chain had been exhausted and when and where a new chain should be started using “theoretical sampling”. When we felt that a particular population (such as Jewish professionals, “New Age Seekers” ) had been saturated, we would stop interviewing its members. On the other hand, when we learned through interviews of previously unknown groups who were using MDMA (such as “postpunk New Wavers” ), we attempted to procure subjects from that group.”

By the tenth month of fieldwork, continual monitoring indicated that we were unsuccessful at recruiting Ecstasy users in employment. Subsequently, interviews for the remainder of the fieldwork period were restricted to those in work. This reflexive procedure proved very successful, and interviewing concluded on the 9th June, 1995.

The questionnaire used was unusual in the sense that although it asked the normal questions about the frequency of use of various illegal and legal drugs, it also asked a great many apparently irrelevant “lifestyle” questions. The reason was this: typically drug researchers just ask about drugs users about their drug use. The only picture that they can thereafter paint of them is as “drug users” – first, last and always, and as if they did nothing else, and were not, as we were to find out, just as “normal”, in practically all respects, as the rest of us. We followed the main questionnaire by administering various well-known psychiatric scales, to test the idea – believed by many – that Ecstasy use leads to depression. In short, we found no evidence of this.7

We also harvested a small sample of head hair from all those willing to donate it, to test the idea that traces of Ecstasy use can be discovered in metabolitic form in hair. The laboratories we used found very little relationship between amount of Ecstasy use that our respondents claimed to have indulged in, and the metabolitic evidence found in their hair. We don't know whether this was because of memory failure and/or consumption of adulterated tablets masquerading as Ecstasy, or because of laboratory error (although we have no reason to suspect the latter).8

What was the Ecstasy Using Sample Like?

The 229-strong large sample was composed of 101 women (44%) and 128 men (56%). Ages ranged from 14 to 44 (average age was 23), with 46 (20%) being 19 years old or younger, 112 (49%) between 20 and 24 years old, and the remaining 71 (31%) being 25 years old or older. The males were slightly older than the females (typical age of males was 21, that of females was 20). Of the total, 221 (97%) described themselves as white.

The target for the sample was “Glaswegians”, and the achieved distribution reflects actual general population distribution of the city reasonably (47, 21% from the city centre; 63, 28% from the West end; 58, 25% from the rest of the city; 36, 16% from the suburbs; and 24, 11% from the immediately surrounding countryside). We don't mean to imply by this that our sample is necessarily representative of the city: just that we succeeded in recruiting people from, literally, all “walks” of life in and around Glasgow. Males were more likely to reside in the West end and in the rest of the city, and females more likely to come from the suburbs and from the surrounding countryside. Younger people were far more likely to live in the suburbs, and much more likely to live with their parents, although young women were no more likely to do this than were young men.

Most (191, 83%) were single, with only 7 (3%) being married, and 28 (12%) cohabiting. The sample only had 19 children between them, and these were no more likely to belong to the married or cohabiting members than to the single ones. A large number lived alone (103, 45%), a further 61 (27%) lived with their parents (particularly, the younger members of the sample), with the remaining 65 (28%) living with partners or friends. Males were slightly more likely to live on their own, and females slightly more likely to live with their parents. Only about a third (80, 35%) lived in owned accommodation, with the remainder being in either state or private rental sector. Those living with their parents were only slightly more likely to be in owned accommodation than were those who lived alone or with others.

Education levels attained were rather higher than those typical for most groups of researched drug users and more similar to the cocaine users we studied before we began to research Ecstasy use.9 Thirteen (6%) had no qualifications, 46 (20%) only O levels, 72 (31%) had A levels or equivalent, 42 (18%) a college qualification, 45 (20%) a university degree, and, finally, 11 (5%) a postgraduate degree. There was no gender difference, but an obvious age one. Although more educated than many other drug user samples, this sample was not as educated as the 100 Ecstasy users studied by Beck & Rosenbaum, of whom, 72% had a university degree.

About a third (79, 35%) were working when interviewed, with another third (73, 32%) being on unemployment benefit, 52 (23%) being students, and the remainder (25, 11%) being either sick, home-bound or on an employment training scheme. Men were much more likely to be in receipt of unemployment benefit, and women were slightly more likely to be in work, or studying. Those in receipt of unemployment benefit were also more likely to claim an illegal income. Class is always difficult to establish. Here, each respondent was asked for both his father's and mother's occupation, and the typical paternal occupation was B; for maternal occupation, C1. Respondents reporting fathers in low status occupations tended to report mothers in the same or slightly higher status occupations. Those reporting fathers in high status occupations tended to report mothers in the slightly lower or markedly lower status occupations.

Respondents were asked to detail their weekly income, divided into their total illegal income and their total legal income. Most people (158, 71%) claimed to have no illegal income (and 5 no legal income). Most of the 66 (29%) with an illegal income made less than £50 a week this way, and most of these only had a small legal income. The few with the larger illegal incomes tended to have large legal incomes. Males were more likely to be the bigger earners in total, and this was also true for illegal income. Older people had bigger legal incomes, naturally enough, although this was not true for illegal income, where those aged 20–24 were more likely to be the big earners than those aged 25 and over.10

When the non-users were compared to the Ecstasy users, the former were slightly more likely to be female, were roughly the same age, had similar marital status, were no more or less likely to have children, were drawn from the same locations, and had similar living arrangements. The non-users were considerably better educated, although were no more likely to be in work or in receipt of unemployment benefit, and their incomes were broadly similar.

All respondents who had ever taken Ecstasy answered an array of questions about their lifetime use of Ecstasy, and a very extensive set of questions relating to their use of Ecstasy in the 12 months prior to interview. These included estimations of the number of days on which they had consumed Ecstasy for each of the previous 12 months, together with an estimation of how many Ecstasy tablets they had taken on each day of use.

Their Use of Ecstasy

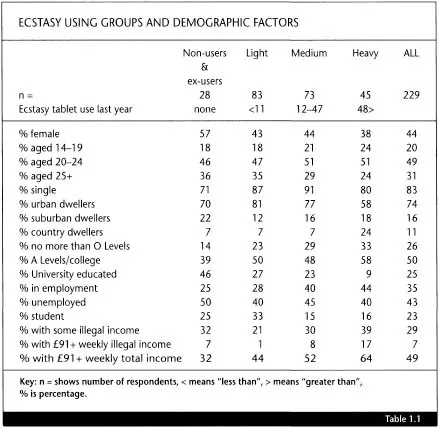

We then used this information to classify our users in terms of their tablet consumption in the past 12 months. The result is in Table 1.1.11 Eight users had not used in the past year, and so are grouped with the 20 non users. The “Light” users had consumed between 1 and 11 tablets in the previous year (broadly speaking, their averaged consumption was “less than monthly” ); the “Medium” users had consumed between 12 and 47 tablets in the previous year (similarly, their averaged consumption was “more than monthly but less than weekly” ); the “Heavy” users had consumed 48 or more tablets in the previous year (their averaged consumption was “more than weekly but less than daily” ).

As one would expect, older people were more likely to have used more Ecstasy, but this was not as marked as it could have been. Even though the trend was for older age groups to have used more Ecstasy, nevertheless substantial numbers even of the youngest group had used Ecstasy extensively, and many of the oldest category were members of the lowest Ecstasy using group. The lack of a strong correlation between Ecstasy use and age is, from a perspective of drug use research in general, rather more remarkable than the slight relationship found. However, this may be because Ecstasy is believed to have appeared suddenly, and in large quantities, in the late 1980s, having previously been scarce. This would have restricted the opportunity for older people to have used it for longer, and thus to have consumed more.

There was no great relationship between gender and Ecstasy using group (although males were more likely to be heavy users, they were also more likely to be light users), nor between different user groups and domiciliary residence in or around Glasgow, or marital status, but there was one between attained education and Ecstasy use.

Compared to the others, some heavy users were most likely to be unqualified, but others were, conversely, those most likely to have a postgraduate degree. The typical level of attainment for each group was Highers/A Levels. There are differences, but not in any obvious or straightforward direction. Non-users were most likely to have a ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Ecstasy and the Rise of the Chemical Generation

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction—Getting into Ecstasy

- Chapter Two Types of Ecstasy User

- Chapter Three Uses of Ecstasy

- Chapter Four The Role of Ecstasy

- Chapter Five Ecstasy—Impressions and Reality

- Further Reading

- Appendix The Information Needs of Ecstasy Users

- Index