- 22 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handling Death and Bereavement at Work

About this book

An estimated 3,500 people die every day in the UK. If someone at work or their partner or close family member dies, managers and colleagues need to respond appropriately. This book breaks new ground in placing bereavement on the management agenda. It addresses some challenging questions such as:

- What to say and what not to say?

- How to balance the needs of the person and the job?

- How do you get it right in a diverse, multi-cultural workforce?

- How do you decide what time off is reasonable?

- How can other people at work help, as well as avoiding making the situation worse?

This book is an essential guide for anyone in an organisation who has to take responsibility in the event of death. It covers issues such as what do in the event of a sudden death at work, managing staff who are terminally ill, and practical help after death including funerals. It is a unique and constant point of reference for anyone concerned with one of the most challenging issues to be faced in the workplace.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handling Death and Bereavement at Work by David Charles-Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliverySection 1

Dealing with loss and bereavement

Chapter 1

What are loss and bereavement?

‘NOBODY DIES WISHING THAT THEY SPENT MORE TIME AT THE OFFICE’

In informal discussion at a recent leadership development workshop, the work-life balance issue came up among a bunch of managers. They all felt that it was a struggle to have a reasonable life outside work and still demonstrate credibly the commitment and passion for their business that was expected of them. It’s a common disease in organisations and a dilemma for the people who work in them. Equally, ‘nobody dies wishing that they spent more time at the office’ is a thought that many people have, even if it sometimes feels too heretical to speak out loud in a workaholic culture. Death pushes us to sort out and re-evaluate what is really important: that is one of its gifts, even if for some it comes too late to do much with the new insights that can emerge from a brush with death, our own or someone else’s.

Bereavement provides us with at least a small opportunity to show our human commitment to other people, irrespective of status, at work. But beyond all of that, there is a deep sense in which we are all equal as human beings. You do not have to be religious to be moved by the sentence from the funeral service: We brought nothing into this world, and we take nothing out.1 Bereavement provides us not only with an opportunity but also a responsibility to support those affected by death for their sakes and that of the motivational health of the organisation.

DEFINING BEREAVEMENT

Bereavement has been described as the process of adapting to loss incurred through death.2 It involves grief, which can feel overwhelming in the case of someone important to you. Grief itself varies, according to a number of factors, such as the depth of the relationship and how timely the death may or may not have been. The dictionary3 equates being bereaved with being bereft, which means to take away, especially by death. Bereavement can also mean that we have lost something or someone. So it can feel either active or passive or both. We look further at efforts to make sense of this in Chapters 5 and 11. The active and passive meanings of death also mirror our active and passive responses considered in Chapter 2, Elements of Bereavement. Anger can stimulate a more active image of death as an enemy with whom we are drawn to struggle, while our sadness fits a more passive understanding of death about which we can do nothing.

Although bereavement usually refers to a loss through death, the word is sometimes applied to other kinds of loss. From childhood onwards we experience many kinds of loss, with which we have to cope, such as toys being broken, leaving home to go to school, a change of school, moving home or a parent leaving home through a relationship split. We experience the reaction of others to our distress, and also notice how they deal with their losses. Because the life expectancy of most pets is so much less than that of humans, virtually all of those who have pets experience their death. This early conditioning contributes to our emerging personality and helps to prepare the ground for the way that we learn to cope with losses, including, ultimately, our own mortality.

The actress Sheila Hancock has written, vividly about her relationship with her husband, John Thaw, about which she has said, “After John’s death, I longed for a book that could honestly tell me how ghastly death is”.4 I hope that in this book the traps of pulling the punches and sentimentalising death have been avoided. On the other hand, our experience of dying and bereavement is integral to being alive with all the good that can bring. Grief is the price that we may pay for love, friendship and life itself.

THE TASK OF BEREAVEMENT

Bereavement is a journey, in and through which we need to come to terms with loss to the point where we can re-evaluate our life and move forward. This means beginning once more to value what we have, so that we become slowly a little less preoccupied with what has been lost. This is not to devalue the person who has died or what they meant to us, but is a matter of shifting the balance of attention towards what is still of value and makes our life worth living, even if at first this may be hard to find: there is hopefully still something to live for after all.

The idea of bereavement as a wound can also be helpful. A wound takes time to heal, and in the meantime it is important to avoid it becoming infected. We need to treat the wounded with great care. The subtle process of healing will, as with a physical wound, be happening to a considerable degree invisibly and unconsciously.

William Worden has described four tasks of mourning:5

Task 1: To accept the reality of the loss.

Task 2: To experience the pain or emotional aspects of the loss.

Task 3: To adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing.

Task 4: To relocate the dead person within one’s life and find ways to memorialise the person.

The latter is a response to the need to let go of the person, because there is also a deep sense that one will never, and indeed does not want to, forget a person who was important to us. Alice, aged 11, wrote down in her diary the day that her grandfather died: ‘I will never forget Granddad’. And she didn’t.

Some, perhaps many, past details about people are forgotten after they die, and this can be distressing, because it’s as if it is only the memories of them that survive. We can forget just as much from the past about the living, but it matters less, because they are still there. Indeed, recalling old memories with friends can be a great pleasure as events are brought back that had been forgotten. Memory retention works differently for different people; it is not a measure of love or commitment to the person that has died.

The task of bereavement is to begin to withdraw emotional energy from the relationship with the person who has died and to reinvest it in existing and new relationships with the living. Before we can do that, a series of powerful responses needs to be worked through, allowing as much time as is needed, which is often rather longer than anticipated. During this process, the bereaved person may swing between grief, during which they are experiencing and coming to terms with their loss, and ‘restoration’, when they are focusing on the present and learning to cope with the future without the deceased.

Separating emotionally from a dead person is not easy, because the bonds we develop with each other are so powerful and necessary to our survival as social animals. We need the loyalty and commitment to each other, if our teams, work groups and families, as well as other working and personal relationships, are to function well. Arguably our passion for each other is a key to our success as a species. How many people bond with a sports team? Manchester United evokes a sense of ‘we’ and ‘us’, almost as powerful as any tribe, even among some who have been nowhere near the city. On a more personal level, this commitment in a family tends to be visible at the rituals surrounding birth, coming of age and marriage, as well as death. Many relatively trivial routines at home and at work can also strengthen our relationships with each other too. To break such powerful bonds of attachment, without denying the love that may outlast all the grieving until the survivor himself/herself dies, is a complex task.

A particularly poignant example of this is the death of a child, possibly in itself the hardest of all losses. When there are other siblings who survive, the parents have to grieve sufficiently but somehow maintain their eye on the ball of parenting and loving the children who survive. If they grieve inadequately, the surviving children may feel that they did not really care for their brother or sister, and perhaps by extension for them. If they grieve too wholeheartedly, they may feel that you have to die to be really loved. It is an extremely tough balance to strike.

For birds it seems much simpler, as the hedge sparrows feed the baby cuckoo, apparently oblivious of their own babies lying dead on the ground below, turfed out of the nest by the interloper. On the other hand, it is not necessarily only humans who mourn: elephants, for example, express what appears to be real grief at the death of one of their number.

During bereavement, this balancing and moving from grieving for the past into living in the present is necessary for survival, physical as well as emotional. Switching in and out of grief is often unpredictable to the bereaved person, let alone those who work or live with them, because it is usually an unconscious process, not easily managed to fit the convenience of external timetables, especially at first. A sign of the person moving through bereavement, however, is the sense that it is more controllable. The bereaved person becomes more able to choose when to move into grief and to be less at the mercy of being overcome suddenly and without warning in public or semi-public situations. To make this kind of progress usually means being able and prepared to allow the emotional pain to surface in order to speed up the healing process. Repressing pain does not make it go away, but rather tends to bury it deep, so that it grows like a destructive weed to take control and distort the way the mind works in the longer term.

MULTIPLE LOSSES

Multiple losses also complicate some bereavement. Recovering from a divorce, a redundancy or a death of someone close to us draws on the same pool of emotional and physical energy and resources. If two or even more such losses happen at the same time, they may feel overwhelming, whereas one of the losses on its own is likely to have been much more manageable. An attempt is made to quantify this in the ‘Life Change Index’,6 at the end of Chapter 15. The Index illustrates the wide variety of loss, to which we are prone, by just living in a world, full of change, risk and danger. They can vary from the end of a relationship, job or career, to the break up of a family (due to emptying the nest, emigration or a feud), to the loss of a physical faculty or a limb through amputation or illness.

SECONDARY LOSSES, AT AND AWAY FROM WORK

Loss in bereavement may be further complicated by losses secondary to the primary loss of the person through death. If the deceased has been the major breadwinner, their surviving partner may experience the loss of the life-style they both enjoyed or the status that the other person made possible. If an only child dies, the man or woman is no longer a parent. A surviving parent finds that they may not feel so welcome at social occasions with former friends, insensitively dependent on socialising interminably in couples. The marginalising and even rejection of some bereaved people who have become single, by former apparently friendly couples, is the absolute opposite of genuine friendship. It is hurtful at a time when they are at their most vulnerable and is sadly far from rare.

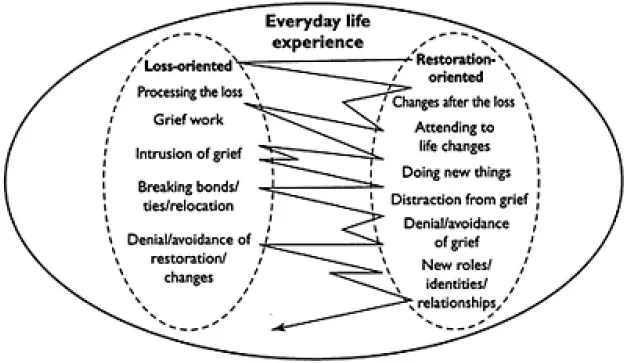

A bereaved person may have to make various, sometimes quite profound, changes in the way they live and think about their lives, especially if the person was close in practical as well as in emotional ways. The life together has itself died with the loss of the other person. A new life has to be created without them. There follows, therefore, a period of adjustment and, quite possibly, learning or even training, which is interwoven with the process of grieving. Stroebe and Schut have depicted the tension in this ‘dual process’ in a helpful model:7

Figure 1 The dual process model of coping with bereavement

Source: Stroebe and Schut, 1999:213

The bereavement process is seen as constantly moving from being preoccupied with the loss to putting that on one side for the moment and getting on with life, but there is a tension in shifting our energy between two such demanding sets of needs. If one predominates, it can lead, on the one hand, to repressing our grief and failing to allow it to begin to heal or, on the other hand, to neglecting the basis of our life for the future: work, health and key relationships.

This model is music to the ears of those who know that work is not for most people a luxury to be picked up when you feel like it. It is a necessity for the individual and society: work is necessary for survival. So the resolution-oriented tasks of the Stroebe and Schut model can be linked to the need to ‘get on with things’. This is of course not just good for the organisation but can be therapeutic too for the bereaved person: a veritable win-win, so long as managers are aware that it is not the whole story of the longer-term working through a bereavement. On the other hand, some employees may lose their work, if only temporarily, as Annie Hargrave, quoted also in Chapter 3, did when she stopped her work as a counsellor because her 21-year-old son was diagnosed with an incurable form of cancer in July 2001. She subsequently wrote, ‘It wasn’t a difficult decision but it was a huge loss which came on top of this devastating blow to the core of my life. I lost my independent life, I lost the daily company of my colleagues, I lost the value of the involvement in the world of my vocation, I lost my income, which wasn’t immediate, but was very significant. I lost the patients to whom I was very committed and I lost the experience of competence. I am competent and pleased to be so. Not perfect, but competent’.8

Such secondary losses may require resolute and enlightened compensatory changes in behaviour. New tasks may not fit gender stereotypes, which may have been part of the relationship previously. So the elderly person, with a minimal overlap of roles in their past relationship with the deceased person, learns to live alone and to master new skills: cooking, paying the bills, changing a plug, doing the shopping, using the lawn mower or washing machine. A young husband with a job that takes him away a lot may have to find new, possibly lower paid, work to be more available for the children and perhaps manage a tighter budget. A young mother may have to find work outside the home, possibly for the first time, without the children being neglected. She may even have to move to a smaller house in a different area if she cannot afford the mortgage. Children may have to change schools or no longer find anyone at home when they return from school.

Sometimes neighbours can be wonderful. When I moved to Oxford to a new job with my nine-year-old daughter after my first wife’s death, she usually came home from school two hours before I did. Although there were friends who came in from time to time, our retired next-door neighbour, Mrs. Bruce, always left some fresh sandwiches for her on the kitchen table, a signal that she could pop round if she had any worries. Looking back on those days, she has told me what a comfort that was, even though in reality she did not spend much time next door. Little things, coming with thoughtfulness and genuine concern, can mean a lot.

Even when we ‘only’ have to cope with a single death, we may through that death be experiencing a multitude of losses, such as companionship, support, a sexual relationship, co-parenting, help, knowledge, skills, shared interests, pleasure and laughter.

In the workplace, there may be a whole raft of secondary losses with the death of a colleague, including many, if not all, of the ones just mentioned. A secondary loss is thus one that comes as a by-product of the main loss. Someone with whom we work closely dies and we find, for example, that we may have also lost:

- a fishing, drinking or bridge partner;

- someone who could sort out the computer when it goes wrong;

- someone else who could stand up to our boss, without him losing his temper;

- a person who knows what it is like to have worked for the company;

- a good sales person;

- a fellow fan of Bolton Wanderers;

- someone in the team with a sense of humour like mine;

- someone at work who got on with my wife and helped to make social occasions at work enjoyable for her.

THE IMPACT OF BEREAVEMENT ON RELATIONSHIPS

Fundamental to all good relationships is respecting and understanding each other—easy to write, but much less easy to do. This acceptance can, however, often feel particularly difficult in the face of bereavement.

Partnerships sometimes experience great pressure after bereavement due to the different ways each person responds. Aft...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Section 1 Dealing with Loss and Bereavement

- Section 2 Facing Death

- Section 3 The community, Death and Bereavement

- Section 4 The Workplace, Death and Bereavement

- Section 5 Case Studies

- Section 6 Appendices