eBook - ePub

Gender Issues in Clinical Psychology

- 245 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender Issues in Clinical Psychology

About this book

Clinical psychology has traditionally ignored gender issues. The result has been to the detriment of women both as service users and practitioners. The contributors to this book show how this has happened and explore the effects both on clients and clinicians. Focusing on different aspects of clinical psychology's organisation and practice, including child sexual abuse, family therapy, forensic psychology and individual feminist therapy, they demonstrate that it is essential that gender issues are incorporated into clinical research and practice, and offer examples of theory and practice which does not marginalise the needs of women.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender Issues in Clinical Psychology by Paula Nicolson, Jane Ussher, Paula Nicolson,Jane Ussher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Gender issues in the organisation

of clinical psychology

Paula Nicolson

Introduction

Despite the preponderance of women as consumers of mental health services, frequently used texts for counselling and psychotherapy focus no specific attention on the particular needs of women clients (Fabrikant, 1974). Only a minority of training facilities make any attempt to train students to provide adequate services to women (Kenworthy, 1976). The difference in client responses to male and female therapists are seldom discussed: most texts are written as if all therapists were male.(Howell and Bayes 1981: xi)

These points raised in an American text on women and mental health draw together crucial dilemmas currently alive in the organisation of British and American clinical psychology training and practice. Women as clients, trainees and practitioners of clinical psychology are subordinate to men and it comes as no surprise that recent efforts to highlight sexual inequality as a key issue on clinical training courses led to reports of:

difficulties addressing these issues at a time when the profession is increasingly staffed by women but headed by men. Some course organisers avoided talking about sexual inequality in training and identify the ‘real issue’ as how to attract more men into the profession. It was also evident that many female trainees felt that it was illegitimate and risky to talk about sexual inequality in the context of hierarchical relationships with male trainers and supervisors.(Williams and Watson 1991: 1)

In this book we explore the full spectrum of gender inequality at all levels of the profession. In this chapter, in particular, I examine and explain the inherent sexism in the structure of clinical psychology practice. To do so, I identify sexist practices in the discipline of psychology as a whole.

Psychology has traditionally been a male-dominated discipline at all levels of the profession and scholarship. Since the beginning of the 1980s, however, there has been a perceptible shift in the gender balance so that in 1989 around 79 per cent of first year UK undergraduate students were female (see Morris, Holloway and Noble 1990).

This has several implications for gender relations and the debate on gender in psychology provides fascinating insight into the way psychology as a whole, and clinical psychology in particular, is organised. The fact that undergraduates in psychology are now more likely to be female than was the case ten years ago, has provoked responses from the psychological community that distinguish it in a negative way from other professions (see Hansard Society 1990). While the focus of other professions appears to be on promoting equal opportunities and encouraging women to seek promotion, in psychology the perceived problem is the absence of men.

The gender imbalance amongst psychology applications, with four-fifths of first year psychologists being female is an issue that needs addressing. Is it that psychology is particularly attractive to female applicants or are potential male applicants deterred for some reason?(Morris, Cheng and Smith 1990b: 10)

There is no evidence to suggest that the previous absence of women provoked any such interest at all!

Gender appears to become an issue when the male dominance of a profession might be threatened, and in the current climate of equal opportunities reforms in even the most traditional disciplines, the resistance to the ‘ecology’ by the international psychology communities requires investigation.

Despite this, women have not been totally discouraged from moving beyond first degree level to take clinical psychology qualifications (see Tables 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4) and PhDs. In 1987 53.3 per cent of all USA doctorates awarded in psychology went to women (APA 1988) (cf 22.7 per cent between 1920 and 1974 and 36.9 per cent in 1978) and half of those currently achieving psychology PhDs in the UK are women (Squire 1989).

Such trends have produced a mixed bag of responses from feminist ‘applause’ to ‘qualification’ by both women and men manifesting severe anxiety about the cause and the effect of these patterns.

| Females | Males | |

| N = 2,037 | 1,152(56.55%) | 885 (43.45%) |

* Membership of the DCP is restricted to those with a BPS recognised qualification in Clinical Psychology (from: Morris, Holloway and Noble 1990)

| 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | |

| Male | 195 | 196 | 163 |

| Female | 580 | 618 | 566 |

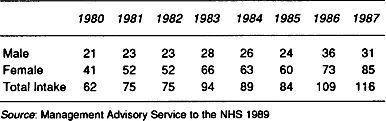

Table 1.3 Intake of students in England between 1980 and 1987

| Females | Males | |

| Birmingham | 18 | 1 |

| East London | 6 | 2 |

| East Anglia | 4 | 2 |

| Edinburgh | 5 | 5 |

| Exeter | 10 | 3 |

| Glasgow | 8 | 1 |

| Institute of Psychiatry | − | − |

| Lancashire | 5 | 2 |

| Leeds | 6 | 5 |

| Leicester | 10 | 5 |

| Liverpool | 11 | 5 |

| Manchester | 6 | 2 |

| Newcastle | − | − |

| North Wales | 4 | 0 |

| North West Thames | − | − |

| Oxford | − | − |

| South West | − | − |

| South East Thames | 6 | 2 |

| South Wales | 11 | 4 |

| Surrey | 12 | 2 |

| UCL | − | − |

| Wessex | 3 | 2 |

Source: J. Williams, University of Kent

Although the increase in women PhD recipients is a positive development, serious questions have been raised about psychology becoming a female dominated profession with the loss of prestige and financial remuneration usually evident in such situations. Although this pattern — the devaluation of female intensive occupations — has been well documented, the exact cause(s) or progression is not conclusively known.(APA 1988: 9)

In clinical psychology in the UK (Table 1.1) although there are slightly more women members of the BPS Division of Clinical Psychology (DCP) the proportions are more ‘equitable’ than either the number of applicants to training courses would suggest (Williams and Watson 1991) (see Tables 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4) or the expressed interest of undergraduates in seeking future clinical training (Marshall and Nicolson 1990). Although not all clinical psychologists are BPS members and thus these figures should be used with caution, Barden et al. (1980) found that most NHS clinical psychologists are in fact Division members.

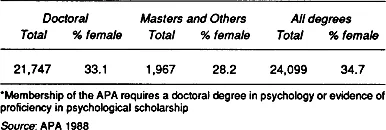

In the USA, however, there are fewer women APA members with clinical qualifications than there are men and these women are slightly more likely to have a doctorate (which is strongly encouraged) than their counterparts in the UK (see Table 1.5).

Table 1.5 Membership of the American Psychological Association's* subfield of clinical psychology and qualifications

The debates within clinical psychology referring to the enthusiasm of women to join the profession reveal reactionary attitudes which are contrary to both equal opportunities and Government/EC policy:

Almost all current trainees are female. The trend towards an increasingly female intake was first commented on in an article by Humphrey and Haward (1981) in which they said, ‘if this trend were to continue there may well be cause for concern’. The trend has indeed continued and I believe there is cause for concern. First, there is the practical problem of a nearly all-female profession providing services to men. If the situation were reversed I am sure there would be numerous letters of complaint from women and quite rightly so. However, the problems of a female dominated profession are not just the mirror image of a male dominated one. Whilst the BPS adheres to a non-sexist policy, the world at large is not necessarily so enlightened. National pay rates for women are significantly below those for men. Predominantly the female professions are lower in status and pay than predominantly male professions. Compare a nurse, teacher or occupational therapist with a surgeon, accountant or barrister.As pay and status in clinical psychology have fallen, so men are no longer being attracted into the profession but as the profession becomes increasingly all-female, so it will become harder to persuade general managers, mostly male, to improve pay and status: a downward spiral of a declining profession.(Crawford 1989: 30)

These attitudes are tragic as well as retrogressive. Crawford (1989) admits that the competition for training places is highly competitive, therefore the assumption must be that only the most able women and men are accepted. The places are filled by very able women, but there is clear evidence that they are not reaching positions of power in clinical psychology which represents a sad wastage of human talent and severely deprives the profession and service users (see Table 1.3). Further, the staff/trainers on professional courses reflect a gender imbalance in favour of men as the trainers with women as trainees — corresponding with the female-male ratio in academic psychology overall (Kagan and Lewis 1990b).

In order to understand and explain why the gender imbalance in favour of males is sustained, it is necessary to look beyond openly sexist challenges such as that of Crawford (1989). They are but the tip of the iceberg leading investigations as to why women's opportunities are curtailed up a blind ally! It is not these open expressions of ‘gender war’ but the covert discriminatory practices that occur everyday at all levels of the profession that produce inequalities. That they are often so embedded in social norms that they occur without most people being aware of them as sexism is part of the fabric of western applied and academic psychology.

The notable absence of gender as an issue in the two influential UK reports on clinical psychology (MAS 1989; MPAG 1990) provide indices of this sexism. The very exclusion of gender discussion when there is quite clearly a balance of power in favour of men is an effective means of making women invisible.

The debate about how far explicit inclusion of gender is problematic for women is an intriguing one. It is the uncontested view of the authors of all the chapters in this book that ignoring gender in any context where there are clear issues of power imbalance is equivalent to enabling men to maintain the balance in their favour. The rhetoric employed to prevent feminist scrutiny (as opposed to the sexist assertions about gender balance quoted above) penetrate both female and male consciousness so that women achieving success are often the fiercest advocates of ‘gender neutrality’. That is, they favour gender blindness over explicit equal opportunities. But exactly who operates gender blindness? When men's backs are to the wall, as wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Gender issues in the organisation of clinical psychology

- 2 Science sexing psychology: positivistic science and gender bias in clinical psychology

- 3 From social abuse to social action: a neighbourhood psychotherapy and social action project for women

- 4 Consultation: a model for inter-agency work

- 5 Mad or just plain bad? Gender and the work for forensic clinical psychologists

- 6 Working with families

- 7 Masculine ideology and psychological therapy

- 8 Working with socially disabled clients: a feminist perspective

- 9 Feminism, psychoanalysis and psychotherapy

- 10 Feminist practice in therapy

- Name index

- Subject index