eBook - ePub

Mental Health Issues and the Media

An Introduction for Health Professionals

Gary Morris

This is a test

Share book

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mental Health Issues and the Media

An Introduction for Health Professionals

Gary Morris

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Mental Health Issues and the Media provides students and professionals in nursing and allied professions, in psychiatry, psychology and related disciplines, with a theoretically grounded introduction to the ways in which our attitudes are shaped by the media.

A wide range of contemporary media help to create attitudes surrounding mental health and illness, and for all health professionals, the ways in which they do so are of immediate concern. Health professionals need to:

- be aware of media influences on their own perceptions and attitudes

- take account of both the negative and positive aspects of media intervention in mental health promotion and public education

- understand the way in which we all interact with media messages and how this affects both practitioners and service users.

Covering the press, literature, film, television and the Internet, this comprehensive text includes practical advice and recommendations on how to combat negative images for service users, healthcare workers and media personnel.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Mental Health Issues and the Media an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Mental Health Issues and the Media by Gary Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The mental health—media relationship

What is this book about?

This book is primarily about a relationship. It addresses the ways in which we as individuals and collectively as a society interact with mental health issues and the extent to which this relationship is changed as a result of media exposure. What we know or how we feel about those who are categorised or labelled as ‘mentally ill’ is subject to continual change and is influenced by the type of information accessed and the degree of credibility afforded its source. The range of messages that carry mental health themes is vast and we are exposed on a daily basis to a plethora of themes through an ever-increasing selection of media. All of this plays a significant part in the construction of what we know or what we feel about issues connected with the topic of mental health and our ways of relating which may either be of a connecting or distancing type. This relates to the degree to which we are able either to connect with and get closer to understanding the inner world of those affected by mental health problems or to maintain a ‘safe’ but uninformed distance.

The first element of this relationship concerns what we know. Much of what we learn about the world around us comes from messages transmitted by the wide selection of media types available. We are literally bombarded with segments of information from the moment we wake until the time of finally retiring to bed. On a typical day this might include trawling through the paper, watching television, listening to the radio, visiting Internet sites, watching a film and reading a book as perhaps the more obvious means. We also engage with other media messages from formats such as advertising, stage production, the music industry and the world of art. All of these examples have multiple sub-divisions or genres that further widen the scope and variety of what is on offer. Ongoing advancements within telecommunications and digital television bring fresh new sources to add to this selection. It is important also to consider what is learnt indirectly or second-hand from others who have been exposed to media messages. The chain of communication can be extended to create a form of Chinese whispers with the authority of information being diminished with each successive link. It is hardly surprising therefore that our understanding of mental health issues can end up wildly inaccurate or that it might prove difficult and confusing trying to discriminate between the various sources from which our knowledge originates.

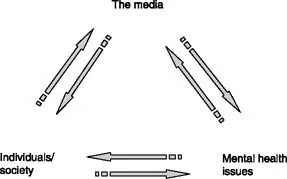

These issues are all explored in detail throughout this book that is essentially (as Figure 1.1 illustrates) about a relationship. This namely concerns a tripartite relationship between: a) us as individuals (or collectively as a society); b) mental health issues; and c) the media. It addresses and examines the myriad of processes that play a part in this relationship and how all of those involved exert a degree of influence over the others. Each participant shares some of the overall responsibility as to the outcome of this relationship as we can, for example, place the blame upon the tabloid press for biased and insensitive reporting although disregard the fact that we as a society are aiding and encouraging this process by continuing to buy their products. Clearly, each of those involved has a distinctly different perspective and separate interests that influence the way in which they relate to certain aspects. It is the significance of these factors and the impact upon the overall relationship that forms the main focus addressed within this book.

In order to begin exploring these themes, it is important to look in detail at each of the following participants within this tripartite relationship: individuals/society; mental health issues; and the media.

Individuals/society

Definitions of the term society include:

‘The institutions and culture of a distinct self-perpetuating group.’

‘The totality of social relationships among humans.’

(Dictionary.com 2005)

Figure 1.1 Tri-partite relationship.

‘The fact or condition of being connected or related.’

(Oxford English Dictionary 2005)

What emerges strongly from these definitions is that society is primarily concerned with a set of relationships between its members with regard to what is shared. The term society can be regarded as a collective entity or broken down into separate components containing individuals or groupings of individuals. The Gestalt focus upon ‘the whole’ being more than the sum of its parts (Köhler 1947) fits very aptly here in that individuals in society should be seen not simply in fractional terms but as dynamic and influential components whose identity is formed through their interaction and relationships with others in ‘the whole’. There are numerous sub-groupings or sets each representing differing values or beliefs. As individuals we naturally belong to a number of these sub-groups each of which has its own collective viewpoints and influences. The family provides us with our first significant group experience and is followed by others such as those encountered through schooling, leisure activities, religion, employment, political affiliation, health care and a potentially endless list of many others.

Individuals hold multiple roles, their relationships being governed by the different sub-groups to which they belong (Epting 1984). Within different contexts what is expected of us, how we perceive ourselves and how we respond will naturally vary. Within the family, for example, as a parent or partner we may have significantly different ways of interacting with others than we do at work with colleagues and employers. We are constantly modifying our thoughts, attitudes and behaviours in response to the accompanying feedback and reinforcers we are exposed to. This can be related to concepts such as social identity or personal identity as identified by Gripsrud (2002). The former relates to what we get from others' perceptions of us and the shared contexts that we are part of (e.g. culture, gender) and the personal identity being what makes us unique and distinguishable from others.

The component individual/society can therefore be regarded as a dynamic and multifaceted entity either regarded as a number of distinct and unique individuals, a varied set of sub-groupings or as a collective whole. The qualities and values held by this component therefore depend heavily upon specific experience and the range of pressures and influences which individuals or groups are exposed to.

Mental health issues

The term mental health issues is a vastly encompassing one having many different attributable meanings. We can consider the actual words themselves, which evoke wildly differing associations and interpretations. The strongest and most impactful of the three words here is undoubtedly that of ‘mental’. It is a word which, depending upon the context of its use, may have either positive or negative connotations. On the favourable side, the word mental can be related to aspects such as cerebral, which denotes enhanced cognitive ability. This word may therefore evoke thoughts of individuals such as Einstein or Newton and signify qualities such as high levels of intelligence. These are esteemed and valued connections that afford a true sense of value and worth to whomever they are applied. At the opposite end of the spectrum is a far from flattering association. It is where the word mental is used as a form of derision, something that greatly undermines and reduces the credibility of the individual it is applied to. It is often used dismissively and seemingly unconcerned about a person's felt experience. When appearing in newspaper headlines it can drastically influence the impression given – for example, the Daily Express's ‘Bruno Put in Mental Home’, or on another occasion, the Independent's ‘Mental Patient Freed to Kill’. The use of words in this manner is commonly found within many media products and serves to reinforce negative attitudes held by the general public.

The wider term mental health issues can be looked at in two contrasting ways but is perhaps more commonly associated with that of mental illness over that of mental well-being. The former term carries a number of stereotypical associations including the exaggerated propensity for violence. This highlights a commonly held fear that those with mental health problems are unpredictable and more prone to aggressive acts than other members of the population (Morrall 2000a). Other negative connotations include the underlying assumption that the ‘mentally ill’ are unable to adequately care for themselves (Health Education Authority 1999). This brings about a pitying and disempowering approach, which diminishes an individual's sense of autonomy or choice. By contrast, the less applied connotation of mental well-being is associated with aspects such as campaigning and health promotion initiatives.

Another association is that of mental health treatment, something generally viewed with a sense of trepidation and fear, borne out of striking and lasting images seen in media examples such as in the film One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest (Seale 2002). This type of portrayal is made more frightening by the strong sense of powerlessness attributed to those receiving care. Examples such as these reflect the destructive culture of institutionalised care outlined in some depth a few decades ago by the social researchers Goffman (1961) and Barton (1976). Clearly, many people's understanding of treatment is inaccurately fuelled by various impactful sources that do not properly convey the range and scope of current care approaches available. Fortunately there do exist within the media a variety of examples showing treatment as a caring process as evidenced in the films Good Will Hunting and Ordinary People that portray the helpful and enabling side of mental health care.

To conclude this section, another issue worthy of mention is the term mental health legislation. This covers a largely polarised set of opinions with, at one end of the spectrum, feelings that not enough control is being taken with unsupervised and ‘unwell’ individuals being left to roam the streets. At the other end, the proposals for added levels of constraint are viewed with some concern, particularly with worries about the ways in which this might further breach and impinge upon an individuals' freedom. Proposed governmental changes in the Draft Mental Health Bill (Department of Health (DOH) 2004) enables people to be detained in hospital and given treatment against their will. While this is welcomed in some quarters in others it is greeted with suspicion and distrust. In particular, comments by the mental health charity Mind (2004a) express concerns regarding the wide range of people and types of treatment included within this new legislation providing for compulsory treatment and loss of liberty. The main argument being raised by mental health advocates concerns the availability of effective treatment and support over that of detention and exclusion (Mental Health Media 2004; Mind 2004a)

The media

The term media can be understood simply as a means of communication by organisations or individuals with a targeted audience. Messages are transmitted via a number of communicating channels and are interacted upon by a receiver primarily through the senses of sight and sound. Information is inputted in forms such as narrative (either printed or spoken), imagery (light, colour, appearance, expressions and gestures) or as sound (music and verbal exclamations).

A number of distinctions are made with regards to the term media including those of mass media and new media. The mass media may be understood simply as a communicating agent that can reach potentially large numbers of people in a diverse range of social settings (Devereux 2003). The concept here of wide reach is supported by McQuail (2005), who indicates the ability the mass media has in acting as a cohesive force connecting scattered individuals in a shared experience. This picture is changing with the advent of new media as the concept of an audience as a mass entity is becoming more fragmented in light of the greater number of media providers and products available. We can understand the term new media with regards to the recent technological developments within telecommunications that notably include the Internet and digital television services (Stevenson 2002).

The media itself is a communicating entity that has provided its audiences with forms of entertainment and education for many centuries. Historically this involved traditional forms such as art, writing and drama. The range of media types available changed rapidly especially with advancements in scientific and technological endeavours from the late nineteenth century onwards. There was a greater accessibility to the written word through the development of the printing press by William Caxton in 1477, commencing with the publication a year later of Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres. Nowadays, an almost limitless array of newspapers, magazines and books are published, geared towards every conceivable format or interest group.

The era of photography began with the announcement on 7 January 1839 of the development of the Daguerreotype, the first successful photographic process. The process consisted of exposing copper plates to iodine, the fumes forming a light-sensitive silver iodide. This led on to the search for animated or moving pictures with early inventions including the ‘wheel of life’ or the ‘zoopraxiscope’, where moving drawings or photographs were watched through a slit in the side. Modern motion picture making began with the invention of the motion picture camera in 1895, largely credited to the Frenchman Louis Lumière. Three decades later, The Jazz Singer, made in 1927, was the first feature length film to use recorded song and dialogue.

The birth of radio dates back to 1885 when Marconi sent and received his first radio signal. In 1924, John Logie Baird demonstrated a television system which transmitted an outline of objects and followed this a year later with an improved system which showed the head of a dummy as a real image. These achievements have continued to develop at a rapid pace with a virtual explosion in the number of channels now offered through cable and satellite services. This has been followed with the advent of digital television and radio services.

This brings us on to new media and in particular the birth of the Internet, whose origins date back to the 1960s with the development of a technology where strings of data were broken down and reassembled at their destination (LaBruzza 1997). This is complemented by further advances in telecommunication technology heralding an era of greater interactivity between the sender and receiver. The huge selection of media products now available does allow for much greater consumer choice although it poses problems with regard to examining the concept of audience reception because of the scale and complexity of the possible channels and sources involved (McQuail 1992).

Relationships

Having looked briefly at each of the participants in turn we can now focus our attention upon the relationship they have with each other leading towards an appreciation of the total relationship.

Society's relationship with mental health

This is an exceedingly complex relationship to describe and perhaps is better understood not by a single relationship but a set of multifaceted ones. Within society, there are many different ways in which mental health issues are encountered. Contact may be close or distant, informed or misinformed, personal or professional. We understand and react to those experiencing mental health problems as a consequence of what we know and what we feel. A core consideration regarding this relationship relates to who within the perspective of society is being considered. The following categorisations provide a useful means of exploring the very diverse range of vantage points involved: personal experience; professional experience; victims of the mentally ill; the mentally ill as victims; and the inexperienced.

Personal experience

Personal experience of mental health problems might incorporate either one's own direct experience as a mental health service-user or as a carer to family and friends. This potential...