eBook - ePub

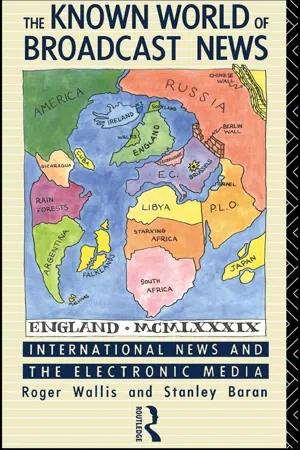

The Known World of Broadcast News

International News and the Electronic Media

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Known World of Broadcast News

International News and the Electronic Media

About this book

Radio and television news are expanding everywhere, often at the expense of print media. Developments in global communications, in theory at least, have made the world smaller. An event anywhere can theoretically be reported anywhere else on radio within minutes; on television within hours. But theory and practice are often far apart. Broadcast News has become a global business, almost like the music industry, with its own 'Top 10' and an inevitable streamlining of taste. A few major organisations control the newsflow. Syndicators guarantee that more and more of us get to see or hear the same stories. This is typified by the growth of independent or local news stations, and cable suppliers, competing mercilessly with the traditional giants of the news airwaves (the US Networks, the BBC and other Public Service Broadcasters, etc.). But does this development satisfy the democratic demands of enlightened society and of informed citizens? This book presents a catalogue of worries, but also some rays of hope. It looks in detail at news broadcasters on both sides of the Atlantic. It also covers the international broadcasting scene as well as third world countries and recent developments in Glasnost's USSR. A major empirical study of what we get from broadcast news (taking the case of the USA, Britain and Sweden) is also presented. Models useful for understanding both the present and the future are suggested.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Known World of Broadcast News by Stanley Baran,Roger Wallis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A day in the life of the world

In the not too distant past many people turned to broadcast news to make sense of a confusing world. Now, though, it seems that it is the world of broadcast news that is topsy-turvy. In the United States, the CBS “Nightly News” programme is a mere darkened screen in homes all across the country as the anchorperson, paid four million dollars a year, fumes in his dressing room. He refuses to go on the air because a late-running tennis match has delayed the start of the broadcast. Hundreds of television journalists are released from their jobs because of budget cuts at all three national commercial television networks. Network newswriters walk out in a labour dispute; 2,000 full-time radio news positions disappear in the US in 1986 alone. Local broadcast stations, using satellite news gathering equipment (SNG), send their own reporters to cover national and international events, reducing their dependence on and the influence of the national networks. Many stations bypass the national networks altogether. The sophistication of news gathering technology grows exponentially, newsreaders’ haircuts become more stylized, and the Congress of the United States holds formal hearings on the crisis in broadcast news.

In Europe, a British government report in the mid-1970s contemplated selling two of the BBC’s most popular radio networks to the highest bidder or possibly allowing them to become commercially sponsored in order to offset the rising annual licence fee. Now, ten years later, the traditional notion of public service broadcasting is being questioned by that same government—the BBC’s licence fee may no longer be sacrosanct; sponsorship and subscription are to replace it.

The call for “free” radio and television (meaning generally deregulation of the structures governing commercial broadcasting) has become a political campaign issue in Sweden, as of now the last remaining nation in Western Europe that does not have national commercial radio or television channels. Even Sweden, however, is likely to go commercial in the near future. The competitive pressures in European broadcasting are so powerful that even the most ardent supporters of a non-commercial, public-service ideology may not be able to defend their position much longer.

In Germany, where people with cable television can watch satellite-delivered Australian drama, American football, and nonstop news, the national public radio networks and stations convene their journalists in meetings like the 1988 Radio-Borse-Regional in Stuttgart. Their task is to plan strategies to best meet the challenge of the slicker, lighter news offered by the newly created commercial outlets.

The philosopher Plato knew nothing of these events when he wrote his Dialogues 400 years before the birth of Christ. One chapter from that work, the Allegory of the Caves, however, suggests a question that we may well ask today: what do we really know about the world around us? Plato’s characters are human beings who have been chained in a cave since childhood and are chained to its walls so they cannot turn their heads and, therefore, can look only straight ahead. Behind and above them sits a blazing fire that casts the prisoners’ shadows and those of the people that pass between the flame and them upon a far wall. “Like ourselves,” Plato says, “they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another…. To them the Truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.”

Like the prisoners in the cave, we too come to know the world beyond the boundaries of our actual experience through the shadows of light and dark electronically beamed into our homes. And if it is true that we know the world (even if only in part) through the pictures of it brought to us by broadcast news, then we need to understand those forces that shape the shadows that shape the perceptions that very often shape our interactions and behaviours in that world.

Plato is not the only ancient author who raised thoughtful questions about how we come to order our experiences of an increasingly complex world. The Udana, a Canonical Hindu Scripture, offers the fable of the blind men and the elephant. In it, six blind men approach an elephant, each from a different direction. All “experience” a different pachyderm. The first blind man touches the beast’s side: the elephant is like a wall. The second fondles the tusk: the elephant is like a spear. The third, the trunk, ergo a snake. The fourth reaches for the knee and of course, the elephant is like a tree. The fifth, meeting the elephant at his ear, is certain that this is a fan-like animal and, finally, the sixth, at the tail, gropes and comes away knowing for sure that an elephant is very like a rope. But what does each know of the total beast? John Stevens and William Porter wrote a book in 1973 called The Rest of the Elephant (Stevens and Porter 1973), but they meant the broadcast industry itself. We mean the world. If viewers in America meet the world from only one “end” and European viewers meet it from a different angle, what does each really know about the world? And what of those in Trinidad, Mainland China, or Kenya? What is our understanding and awareness of them and theirs of us?

Postdating our two fables by a few centuries is Paul Lazarsfeld. Like Plato and the Hindus, this social scientist, who emigrated to the United States from Vienna, knew a world where television, satellite, fibre optics, computers, cable, video disk, videocassette, and other electronic marvels did not exist. Unlike them, though, he did know a world that harboured mass media and mass audiences. Nonetheless, his view of where our world view is heading echoes accurately those of our two ancient but lasting stories. Writing in 1941 in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science (Lazarsfeld 1941:12), he asked,

Today we live in an environment where…news comes like shock every few hours; where continually new news programs keep us from ever finding out the details of previous news; and where nature is something we drive past in our cars, perceiving a few quickly changing flashes which turn the majesty of a mountain range into the impression of a motion picture. Might it not be that we do not build up experiences the way it was possible to do decades ago, and if so wouldn’t that have bearing upon all our educational efforts?

Let’s return to our hypothetical broadcast news listeners and viewers. What experiences of the world do they build from the quickly changing flashes? What truth is contained in the shadows? How would they each describe the world they met on 18 November 1986?

Let’s say that the American encountered the beast at 10:00 p.m. PST on “60 Minute News,” KTVU-TV’s nightly news programme. This offering from an independent TV station in Oakland, California—the top rated news programme in the San Francisco Bay area and, according to the station itself, the “Number One Primetime Newscast in America”—presented the following picture: At 4:00 a.m. GMT on 19 November 1986 (the 18th in America), the BBC World Service news programme “Newsdesk” paraded this view of the world for a global listening public: Two different elephants? Two different galaxies? It is important to note, too, that half of the BBC stories clearly have more than minor relevance for the US: the UN debate on Central America and Nicaragua, goings on in Haiti after the US assisted removal of dictator Baby Doc, Afghanistani torture chambers, British interpretations of President Reagan’s proposal to eliminate nuclear weapons, joint Chinese/American business and scientific ventures. If you had followed any of the five American newscasts we were monitoring on that day, you would have seen nothing of these significant events. Yet the man from Seattle who fell from the Berlin Wall received multiple American coverage (KTVU-TV, CNN and CBS). The ABC Network News had virtually no international news at all that evening. NBC devoted one minute and forty seconds—a very long report in American television news—to the Royal Golf Club of Thailand and its fairways near an airplane runway. CBS, to its credit, ran twenty-second reports on the reactivation of the Chernobyl reactor in Russia and the supply of Soviet weapons to Nicaragua. The arrival of a black US Ambassador to South Africa and a story about drug trafficking in Central America also appeared on CBS.

see table

see table

CNN’s “Headline News,” described by that cable network as “Around the World in Thirty Minutes,” had only two foreign stories on its evening broadcast on 18 November—the murder of the Renault executive and the gravity-plagued man from Seattle.

On the other side of the Atlantic, BBC Television did cover Mrs Thatcher’s thoughts on Reagan’s disarmament plans. Swedish Television devoted a section of its newscast to the Amnesty International report on Afghanistan! torture centres. Both covered the continued fighting in Beirut and an appeal, originally broadcast on Lebanese television, for the release of hostages held in that country. An Eastern European story made Swedish television—a major oil spill into a Czeckoslovakian river had spread into Poland. BBC Network Radio also had an East European item, one dealing with relations between Britain and East Germany.

Both Swedish Radio and Swedish Television gave prominence to a new list of possible World War II war criminals from the Baltic States said to be living in Sweden that was published in, of all places, Washington. Finally, BBC domestic national radio offered two reports from Africa that were only indirectly related to the politics of South Africa. One examined unrest in Zimbabwe and the other dealt with Uganda, a country relegated to news oblivion after Idi Amin was ousted from power by Tanzanian troops.

Why do certain types of international events have low priority on American national newscasts? How can local newscasts, offering a smattering of international news, enjoy apparent rising success (ratings) with their menu of accidents, disasters, violent crimes, and other exceptional (or if they occur with such frequency and regularity, unexceptional) incidents? Is the situation so very different in the US compared to other developed nations?

The answer to this last query is “yes” (at least for now). Nationwide radio and television newscasts in our two-nation European sample, Britain and Sweden, cover a much wider range of activities and geographical areas than do their American counterparts. But given the tremendous speed of technological and economic change in Europe, that “yes” might soon have to be amended.

The ignoring of certain stories and locales is most certainly not an American-only phenomenon, especially as advances in the magic of television technology have enchanted news producers wherever they may live, but it seems to be most acute in the ratings-driven US system. The desire to produce a fast-paced, entertaining, slick news “show” is a difficult temptation to resist in the States. For a time in the early 1980s, for example, “snappy” was the key word at CBS Network News headquarters in New York. The New York Times special report on the travails of that news operation quoted one disenchanted producer (28 December 1986), “It was unbelievable stuff, it trivialized everything. And the correspondents learned that the way you got on the air was to write a snappy script and be entertaining.” Under conditions such as this, it is not surprising when non-visual stories like UN debates are ignored. In fact, during CBS’s snappy period, “oddball animal stories” were highly valued. On one programme two separate stories about eccentric sheep were included in that network’s evening news, a thirty-minute programme allowing only seventeen minutes for reports, five minutes for the anchorman, logo, and flashes of things to come, and eight minutes for advertising. Much of this “dummying down” of the CBS news product was in response to competition from the other networks who were gaining ratings points with new, up-tempo formats.

Such manoeuvring led Neil Postman (Postman 1985:113) to state in his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death,

And so, we move rapidly into an information environment which might rightly be called trivial pursuit. As the game of that name uses facts as a source of amusement, so do our sources of news. It has been demonstrated many times that a culture can survive misinformation and false opinion. It has not yet been demonstrated whether a culture can survive if it takes the measure of the world in twenty-two minutes. Or if the value of its news is determined by the number of laughs it provides.

More recently, the CBS Network News, according to its own people, has been “hardened.” No more sheep. But still not much time for foreign news or goings on at the non-visual UN. Sadly, though,

CBS, considered the “class act” of American television news, has been overtaken by other corporate troubles. With eyes firmly directed toward Wall Street, the need to make even more money from an already profitable company has led to labour disputes and significant cuts in the resources allocated to news gathering.

One very logical outgrowth of this financial/technological environment at the national news gathering and reporting level is the explosion of local broadcast news programmes offering a format of local reports with an occasional foreign story being added as filler.

In view of the troubles plaguing the network news organizations, this development is regarded as highly disturbing to many observers of the journalistic scene. Even in the European context of highly regulated broadcast media, many local lobbying groups are agitating for extended regional and local broadcast media. With the growth of satellite news feeds offering national and some foreign news footage for sale to anyone, local stations can claim to be covering the world on a very small budget. All that’s needed is a local parabolic dish and a local one- or two-person video team keeping tabs on the police and emergency services (to pick up all the fires, car crashes and bodies of murder victims as they’re wheeled off on stretchers). In the totally commercial, virtually deregulated American broadcasting arena, even local affiliates of the major networks are tempted to shun national and international news material, since local news produces local revenue which goes straight into the local stations’ coffers.

As might be assumed, the economics of local news become the important driving force behind what and how things are covered. Yet, if asked, most citizens would admit that there are more important issues at stake in news coverage than short-term profits for those fortunate enough to hold a broadcast licence (despite former US Congressman Torbett McDonald’s assertion that a broadcast licence is nothing more than a permit to legally print money). One, for example, might be whether or not the general public has a right to be informed by those who operate stations as their fiduciaries (according to the terms of the broadcasters’ licence). As one of us wrote elsewhere,

Local television news is good television—fast-paced, exciting, entertaining. The performers are friendly and attractive. It is such good television, in fact, that 40 to 60 per cent of most television stations’ profits come from their nightly local news shows. Local news shows have become so lucrative, that most stations hire “news doctors,” specialists in improving the ratings of news shows, to help spice up those broadcasts in order to draw more viewers which means higher ratings which results in even more profits. (Baran 1980:85)

Radio, television, or print as sources of news

The Television Information Office tells us that over 60 per cent of all Americans get “most of their news about what’s going on in the world” from television. In addition, over half of the people in the US say that television is their “most believable” source of news. Adnan Almaney (Almaney 1970:499), who conducted a classic study of foreign news on the US networks, states boldly and simply, “Television is the primary source of news for most Americans.”

In fact, newspaper reading in the USA is waning, evidencing a 16 per cent drop in the number of adults who read a paper every day in the period from the end of the 1960s to the end of the 1970s alone. The youth of that country read papers less than their parents did at the same age (McManus 1986).

What is obviously filling the growing newspaper reading void is television news. And in spite the growth of audiences for local newscasts, despite the problems that beset these traditional purveyors of broadcast truth, audience figures for the big three American evening network newscasts are still impressive. Although the proportion of the television viewing audience that tunes in one of the network news programmes each evening has dropped from 72 per cent in 1981 to 63 per cent in 1987 (NBC’s “Nightly News With Tom Brokaw” dropped 13 ratings points in that same year), the number of sets tuned in is still impressive. 1989 audience counts show 10.3 million viewers a night for NBC, 10.1 million for CBS, and 9.2 million sets for the ABC Evening News. These figures amount to a sizeable total of the 172 million “TV Households” in America.

Similar sizeable news viewing figures are returned in other countries as well. The main BBC1 evening news at 9:00 p.m. attracts about 9 million viewers on average (20 per cent of the British population). Its prime national competitor, ITN News, does not schedule its main evening news programme at the same time. At certain times of the evening in the USA, on the other hand, a viewer can switch between a variety of different stations and see the same news stories being covered. Many times even the visuals are identical, as the tendency for everyone to sell to everyone becomes more prevalent. Finally, our third sample country, little Sweden with its eight million inhabitants in Northern Europe, has two nationwide television news programmes linked to the two national networks: Channels 1 and 2. Channel 2’s 7:30 p.m. newscast, “Rapport,” which is featured in this study, attracts between 20 and 30 per cent of the population daily (between 1.5 and 2 million viewers). Through spillover into adjacent countries, it also picks up followers in Oslo (Norway) and Copenhagen (Denmark) who can generally understand the Swedish version of Scandinavian.

It should be emphasized that for those who are not satisfied with the amount of foreign news on the broadcast media, there is another alternative—print journalism (tho...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Figures and tables

- Preface What lies behind the truth?

- 1: A day in the life of the world

- 2: Broadcast news in the USA: turmoil, realignment, and restructuring of the traditional operators

- 3: The traditional news broadcasters in Britain: new establishments fighting older institutions

- 4: Medium-sized traditional operators in Europe: the example of broadcast news in Sweden

- 5: Challenging the traditional broadcasters: new players in the news game

- 6: The international news broadcasters: information, disinformation, and improvised truth

- 7: Meeting the elephant: broadcast news views the world

- 8: Which news and why? Understanding the forces that shape the news

- Epilogue What will we know? What should we know?: Comparing broadcast news to developments in other media sectors

- Postscript: A Challenge to European Traditions of Broadcasting

- Appendix

- References