eBook - ePub

Special Educational Needs and School Improvement

Practical Strategies for Raising Standards

- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Special Educational Needs and School Improvement

Practical Strategies for Raising Standards

About this book

Providing a practical guide to strategic management in the field of special educational needs, this text gives the reader a framework for raising achievement throughout the school.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Special Educational Needs and School Improvement by Jean Gross,Angela White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Why plan strategically for SEN?

Introduction

Books on special educational needs traditionally focus on the nature of individual children’s SEN and how to address them. Much has been written, also, on the systems involved in the SEN Code of Practice — IEPs, SMART targets, parental involvement, pupil involvement and other essentially process-oriented and operational themes.

This book is different. It is about how to manage SEN strategically, rather than operationally; it is about managing SEN at a whole-school level, as part of a school’s overall school improvement process, rather than about meeting the needs of individuals.

It is about applying to SEN the familiar school improvement questions (DfEE/QCA 2001):

- How well are we doing?

- How do we compare with similar schools?

- How well should we be doing?

- What more should we aim to achieve next year?

- What must we do to make it happen?

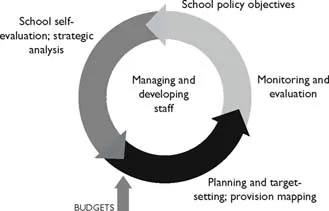

The model used is a cyclical one and looks like this:

Figure 1.1 The school improvement cycle

It begins with setting some broad policy objectives, based on the school’s vision for what it wants to achieve for children with SEN, alongside what it wants to achieve for other vulnerable groups within the wider educational inclusion umbrella.

The next step is evaluation and strategic analysis:

- answering the question ‘How well are we doing?’ in relation to those policy objectives by using a range of quantitative and qualitative tools, which include seeking the views of children and parents/carers;

- using data to answer the questions ‘How do we compare with similar schools?’ and ‘How well should we be doing?’

- looking to the future and the broader context of SEN within education; answering the questions ‘What’s out there?’, ‘What changes are going on in the environment and how might they affect us?’ and

- gathering information about the future profile of SEN within the school: ‘How many children?’ ‘With what types of need?’ ‘In what year groups?’

After evaluation comes planning and target setting: answering the questions ‘What more should we aim to achieve next year?’ and ‘What must we do to make it happen?’ For SEN, this will be a dual process: establishing priorities for the SEN element of the School Improvement Plan (setting improvement targets and planning actions) and simultaneously planning the actual provision which the school will put in place for the coming year in the form of additional adult support.

The next stage is implementation of planning and provision, with the focus on monitoring and evaluating the implementation of plans in classrooms, and the impact on children’s progress.

After implementation comes evaluation, as the cycle begins again.

At the heart of the whole cyclical process is managing and developing staff: the ongoing school systems for helping all staff to evaluate their own practice, learn from one another and from outside, and develop as professionals.

What’s new about managing SEN strategically?

Many schools have found it difficult to apply the questions ‘How well are we doing?’ and ‘How do we compare with similar schools?’ to SEN. At a national level, systems for measuring the attainment and progress of children with SEN in agreed ways which allow for comparisons between schools are still embryonic; use of the ‘P’ scales (DfEE/QCA 2001) is not universal in mainstream schools, and little analysis is done of data that is already available, such as the percentage of pupils attaining at the lower National Curriculum levels at end-of-key stage assessment.

There are deeper reasons for the lack of use of data on pupils with SEN, however. One reason relates to an emphasis in the SEN world on providing support for children with SEN, rather than on the outcomes of that support. The majority of SEN effort in schools and LEAs goes on the complex systems for identifying need and proving (or disproving) the case for additional help (Ofsted/Audit Commission 2002). The goal at school level is often that the child will be allocated funding, and therefore enabled to remain in the classroom with his or her peer group without placing too great a demand on the class or subject teacher. The support, once allocated, is usually long-term; it is more often targeted at ‘coaxing the child to comply with the inappropriate curriculum on offer’ (Gross 2000) than, for example, ensuring that the child attains a certain level in the end-of-key stage assessments.

Much SEN work, then, is about support for individual children, and the processes of the SEN Code of Practice which enable them to access support. There is a degree of focus on outcomes, as defined in Individual Education Plan targets, but these are particular to the child and do not allow for any comparison between schools. They allow schools to answer the question ‘How are we doing for David?’, but not ‘How are we doing for children with SEN in general; for children with behavioural, emotional and social needs; for children with SEN in Key Stage 3; in literacy; in mathematics?’

Because of this, schools are not able to set themselves targets for improvement. They can only set targets for improvement for David. Although the law requires that the governing body reports annually to parents on the implementation of the school’s SEN policy, relatively few schools have set measurable targets which would enable them to report in this way (Thomas and Tarr 1996). Where they have, these are usually about the percentage of children moving ‘down’ from School Action Plus to School Action or to the normal differentiated curriculum — the only statistic which schools reliably gather.

Yet simple measures do exist which schools can use to set targets, and some LEAs have been able to supply schools with information allowing them to compare their own performance with that of similar schools. Chapter 3 of this book will give examples of this approach.

A further reason for the emphasis in SEN on the operational rather than the strategic is the sheer complexity of the processes involved, with their quasilegalistic overtones and quasi-medical approach to diagnosing needs and prescribing remedies. It is this which makes many of those who have had training in strategic management (usually head teachers or aspiring head teachers) to steer clear of applying their knowledge about strategic planning to SEN. They feel de-skilled by its complexities, and by the volume of paperwork it generates. The temptation is to leave those complexities to the person who is often least likely to have had training in strategic management but does know her or his Code of Practice, the SENCO. In these circumstances, a team approach can be lacking.

Again, this is not difficult to remedy; all it takes is a little less anxiety among senior managers about the mystique of SEN, a little more time and status for the SENCO and a realisation that SEN is as amenable to improvement as any other of the school’s spheres of operation. It also takes some tools, and this is what this book aims to provide. Why plan strategically for SEN?

Why manage SEN strategically?

The first argument for applying school improvement processes to SEN is one of equity. Where schools feel driven by the national targets for the attainment of the broad majority of children, and for the more able, it makes sense to set school-level targets also for those who have difficulties in learning. Targets, preceded by self-evaluation and followed by actions that are carefully planned and monitored, do work: we have only to look at the increase in the number of children reaching nationally expected levels at the end of their key stage or at the (short-lived) reduction in permanent exclusions during the period when targets were set in this area to see this. Planning strategically at whole-school level for children with SEN is thus likely to mean that they make better progress and improve their life chances.

A second reason for adopting a strategic approach is the impact this is likely to have on the attainment and progress of children who do not have SEN. At a crude level, taking resolute action to reduce the percentage of children who fail to acquire very basic literacy or numeracy skills before they leave the primary school will make classes easier to teach: the learning of the majority can be all too easily disrupted by the behaviours that stem from the frustration and low self-esteem of those who are not making progress, and who know it.

Less crudely, there is increasing evidence (for example, Wilce 2001) that schools which have focused their school improvement planning on increasing their capacity to include all children, via appropriate staff development and resource allocation, will, as a result, raise attainment across the board. The reasons for this are not hard to see: for every child with complex SEN for whom a teacher learns to make specific adaptations to curriculum delivery there are likely to be several more in the class with lesser needs, who benefit equally — from greater clarity in the teacher’s use of language, for example, or from the use of alternatives to traditional paper and pencil recording, or from class work on how to handle arguments and defuse conflict.

Finally, there are a number of ‘external’ reasons which may encourage schools to embrace lower-attaining pupils in their regular school improvement processes. The main external frameworks for monitoring and accountability now focus sharply on the achievement and participation of all. Ofsted, for example, expects effective schools to have analysed the data on different groups of pupils (including those with SEN), and to set clear targets based on their analysis. The inspection focus has shifted attention increasingly onto the performance of vulnerable children, rather than exclusively on those who do not experience barriers to their learning.

Similarly, the trend towards greater delegation of SEN funding to schools, accompanied by a stronger monitoring role for LEAs, is likely to mean that schools who can show that they are evaluating their own performance with children who have SEN will be well placed to demonstrate their effective use of resources. They will also, if they use information such as that presented in Chapter 7 of this book on ‘what works?’ in different possible interventions for pupils with SEN, be able to demonstrate that they have applied Best Value principles to their job of raising attainment and promoting inclusion for all.

2 How to plan strategically for SEN

STEP ONE: agree your school policy objectives

The first step in being strategic about SEN is having a clear sense, as a school, of what you want to achieve as an outcome for children who experience difficulties in learning.

Figure 2.1 The school improvement cycle

The simplest way to define the outcomes you want to achieve is to discuss, as a staff, how you would complete the sentence ‘We make provision in this school for children with SEN in order that …’. The answers may be varied; for example:

- …in order that every child can reach his or her potential;

- …in order to develop pupils' self-esteem and confidence;

- …in order that all children can access the curriculum;

- …in order that all children leave our school with the core skills (such as literacy, numeracy, personal organisation and social independence) they will need in adult life;

- …in order to raise the attainment of all pupils;

- …in order that all children can be included fully within their peer group; and

- …in order to help all children learn the social, emotional and behavioural competencies they need in order to sustain positive relationships with others.

The sentence completions will generally focus on three areas: attainment; achievement, in the broader sense (including personal and social achievement); and inclusion. Because of this it may be possible to combine them into a single, succinct statement such as ‘Our objectives are to raise attainment and promote inclusion.’

It is necessary to spend a little time clarifying the school's broad objectives in order that these can then be used to generate ways in which progress towards them can be measured — that is by setting SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-constrained) targets, like those on IEPs.

Some definitions of broad objectives lend themselves more readily to generating measurable targets than others. For example, the objective ‘Our aim is for all children to reach their potential’ might be difficult; how would the school know (and be able to measure) whether it was meeting its aim? In many primary schools the only measurement of children's ‘potential’ sits in teachers' heads, and is often either self-fulfilling, with low expectations leading to low attainment (Barber 1996; Blatchford et al. 1989) or just plain wrong. Secondary schools may define potential through CAT scores on entry to the school, which generate predicted attainment levels at Key Stages 3 and 4, but the same arguments hold about self-fulfilling prophecies, and there remain many debates about the validity of any sort of measurement of cognitive ability as a true predictor of what adults or children will achieve in life. Again, CAT scores measure only a limited range of ‘potential’: we are not yet at the stage of assessing all the intelligences (musical, linguistic, spatial, bodily-kinaesthetic, interpersonal and intrapersonal) which have been postulated (Gardner 1993) as central to achievement in its widest sense.

Other definitions of school policy objectives lend themselves more readily to generating measurable targets. ‘Raising attainment’, for example, might lead to a target to increase the percentage of children attaining at least level 1 at the end of Key Stage 1...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Special Educational Needs and School Improvement

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: how to use this book

- Chapter 1 Why plan strategically for SEN?

- Chapter 2 How to plan strategically for SEN

- Chapter 3 School self-evaluation

- Chapter 4 Implementing and monitoring plans and provision

- Chapter 5 School improvement and SEN: a case study

- Chapter 6 Planning provision: using a provision map

- Chapter 7 Planning provision: what works?

- Chapter 8 Beating bureaucracy: minimising unnecessary IEPs and paperwork

- Chapter 9 Developing staff: the SENCO and management team

- Conclusion

- Further information

- References

- Appendix: School improvement and SEN: training materials

- Index