1 ‘What’s needed is a metropolitan plan’

June 16 is now a public holiday in South Africa. It commemorates a day in 1976 when police opened fire on a protest march of African schoolchildren in Soweto, Johannesburg, and it represents a turning point in the long history of resistance to the apartheid government. It was this resistance which, gathering force during the 1980s, was to culminate in a process of political transition to a liberal democratic government, officially marked by general elections in April of 1994.

But 16 June 1989 was still a normal working day for some sections of the South African population.1 It was certainly a normal working day for the officials of the metropolitan and local authorities in Cape Town, although there was no doubt that the wind of political change was making itself felt in the modern, well-guarded buildings which housed these institutions. Significantly, however, 16 June 1989 was to become an important date in the history of metropolitan planning in Cape Town. Although unaware of it at the time, the small group of planning officials who came together on that winter’s morning to discuss the idea of a ‘regional development strategy’ were embarking on a metropolitan planning process which was to become the longest and most extensive yet undertaken in the city. As a planning process which was born in the early days of the political transition, and which has continued through ten years of this transition, it was to mirror in a number of ways the struggles and strategies affecting the country as a whole.

Certain of the planners at this meeting were destined to play an influential role in the subsequent planning process, and they need an introduction. Peter de Tolly, articulate, persuasive and authoritative, was a South African born, English-speaking planner in his forties. He had trained at the University of Toronto and worked extensively there and in the United States. In both his training and subsequent work he had become convinced that process was the key to successful planning and that the ideas of ‘growth management’ were particularly appropriate to the kinds of problems facing Cape Town. At the time of the meeting he was Deputy City Planner of the Cape Town City Council, the largest and most powerful of the various Cape Town municipalities, and generally acknowledged as the ‘core’ municipality of metropolitan Cape Town. A second important role-player was Francois Theunissen. An Afrikaans-speaking South African, he had graduated as a planner from the University of Stellenbosch (one of the three universities in the region and alma mater to many Afrikaner bureaucrats and professionals) and for most of his career had worked in government. Polite, deferential, but very determined, he was most at home with the procedures and regulations which made up the day-to-day work of planning officials of the time. He was at the meeting as a representative of the Provincial government, where his experience had been in statutory planning and development control, but was soon to join the Western Cape Regional Services Council2 (the newly created metropolitan authority) and chair the metropolitan planning process for the following decade.

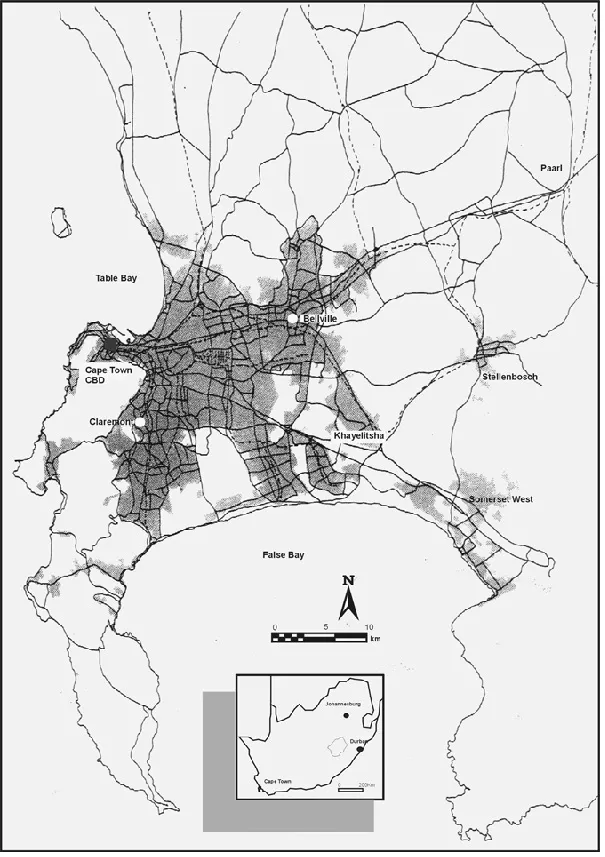

Figure1.1 Locality map of Cape Town.

Figure 1.2 Aerial photograph of Metropolitan Cape Town.

Source: MLH Architects & Planners (2000).

Chairing the meeting on 16 June was the outgoing director of METPLAN, the Joint Town Planning Committee which had previously been tasked with the function of metropolitan planning. With the metropolitan planning function about to be transferred to the Regional Services Council, this man would have been aware that his power base was under threat. As a career bureaucrat who had taken care not to challenge official thinking on urban planning, he was soon to move on to positions in the Provincial and central government administrations. There were five others at the meeting as well, representingvarious local and Provincial departments: all were white, all were male, all mid-career planning bureaucrats. This was not particularly unusual at the time.

What was somewhat unusual was that a group of local authority planners should be meeting in 1989 to consider the need for a metropolitan plan. There were, after all, existing statutory ‘Guide Plans’ controlling the development of the Cape Town metropolitan area. These were typical, comprehensive, ‘blueprint’ land-use plans drawn up in the 1980s by a central government Guide Planning Committee and were mainly concerned with the designation of parcels of land for settlement by different racial groupings.3 It had not, previously, been within the powers of the metropolitan or local authorities to deviate from these plans. It was also significant that the meeting was convened by the new metropolitan authority: the Regional Services Council. This system of supra-local government, which covered both urban and rural areas of South Africa, had been brought into existence by the government in 1985 in an attempt to secure the legitimacy of the crumbling system of racially separate local authorities. The Regional Services Council,4 which formed the second tier of government in metropolitan Cape Town, was ostensibly under the firm political control of the ruling National Party and, in a political system which was highly centralized, there would appear to be little room for questioning a fundamental cornerstone of apartheid – the nature and growth of urban areas.5

However, 1989 was a time of crisis for South Africa and for Cape Town, and as is often the case, planning was viewed as one way of responding to crisis. While our prospective metropolitan planners were setting their agendas for the next phase of their work, on the other side of the city, in the squalid townships and squatter settlements which held the majority of Cape Town’s African and coloured population, a low-intensity civil war was underway. Before following further the efforts of the metropolitan planners, it is necessary to consider some aspects of this crisis.

The ‘tinderbox’ of Cape Town

At the time this story opens, in 1989, an upsurge of resistance to the particular system of racial capitalism in South Africa had made itself felt for nearly two decades. Worker strikes, school stayaways and marches, and civic, women and squatter protests had been met with combinations of state reform and repression. But increasingly, an ailing economy, international pressure, divisions within the ruling party, and the violent nature of internal struggles, made the abandonment of the apartheid project and an acceptance of some form of power-sharing seem possible.

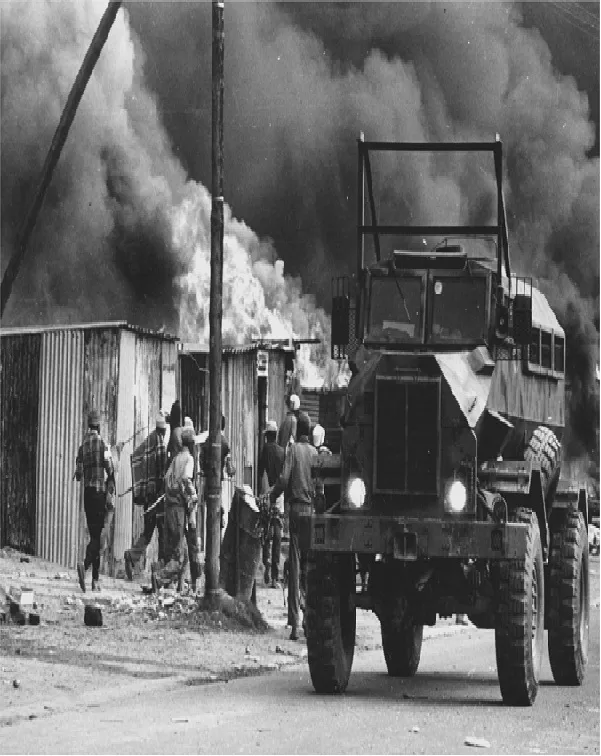

In Cape Town, as in other cities, the issue of physical access to the city became a highly conflictual one. Fierce battles raged between police and squatters (Figure 1.3) throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, as African people without legal rights to remain in the city, as well as those without access to state-approved urban housing, attempted to secure a living space. In what was becoming a familiar pattern of twinned reform and repression, concessions were on occasion granted to those who had the legal right to remain in Cape Town (that is, those with recognized employment), while efforts to prevent further migration from the rural ‘homelands’ were intensified. The residents of the Crossroads squatter camp gained international fame in their efforts to resist removal and demolition. In an apparent exercise of divide and rule, those Crossroads residents with legal urban ‘rights’ or with means of economic support, were allowed to remain in Cape Town and were promised formal housing. At the same time ‘illegal’ migrants were subject to intensified pass raids, arrest and forcible removal back to the rural ‘homelands’ (Cole 1986).However, the emergence of numerous new informal settlements, the estimate that a thousand additional people per day were migrating to the city,6 and the growing strength of squatter resistance organizations, made it clear that the system of influx control was breaking down. In an attempt to cope with the crisis, and in a clear reversal of previous policy, the government announced in 1983 that a large new tract of land for African people would be opened up in Cape Town: Khayelitsha was planned to house some 450,000 people and was located on the remote fringe of the city, some 40 km from the centre.

The government had not abandoned the hope that the delivery of improved urban living conditions would dampen demands for political rights. A series of reforms in the 1980s demonstrated not only a continuation of the twinning of reform and repression, but also the increasing divisions within the rulingNational Party and different approaches adopted by the various government departments. Most important was the official end to influx control, announced in 1986, and a new White Paper on urbanization (Republic of South Africa 1986). The latter accepted that African people could move freely to the cities, but that separate living areas for the various ‘population groups’ in towns and cities should be observed. In particular the White Paper advised local officials to identify new areas of land for African settlement well in advance, bearing in mind national spatial policies which promoted the idea of ‘deconcentration points’ around the major centres. This advice had been taken seriously by officials in Cape Town’s metropolitan planning agency, as we shall see below.

Figure 1.3 An informal settlement (KTC) burns.

Source: Cole (1987).

By the late 1980s the government was under increasing pressure both from beyond its borders (the ANC had called for the intensification of the armed struggle at its consultative conference in 1985, delegations of South Africans had been meeting with ANC heads outside the country, and in 1986 the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act) and from within, where the resistance forces began to regroup in 1989. It was during this period that the government significantly altered the mechanisms through which control and reform were channelled. The National Security Management System (NSMS) had been set up in 1979 as part of the ‘total strategy’, but was only fully activated in the latter part of the 1980s. It represented a ‘parallel system of state power which vested massive repressive and administrative powers in the hands of the military and police’ (Marais 1998, 55). Committees were set up which shadowed each level of regional and local authority, and which essentially shifted the balance of power from the official organs of government to the president and the security forces. The role of these committees was to identify ‘trouble spots’ and to focus on them investment in social facilities and infrastructure, while at the same time collecting information on oppositional movements and attempting to destabilize them.

The NSMS was able to undermine the opposition, but was not able ultimately to contain it. In the first months of 1989 the Minister of Law and Order was able to say that unrest in Cape Town’s townships had abated to such an extent that the government could now press ahead with reform (Cape Times 14/2/89). However, only six months later the streets of Cape Town had ‘been turned into a battleground’ (South Newspaper 24/8/89). The national elections for the Tricameral Parliament, set for September 1989, became the focal point for a revitalized resistance movement. Protest action was initially centred in the schools of the coloured townships of Cape Town, where rallies were held, roads blocked off with burning barricades, and vehicles stoned. From the schools, the unrest spread to the universities and eventually into the centre of the city, where running battles between demonstrators and the police became a daily event. Two weeks before the election Cape Town was recorded as the country’s worst trouble spot (Star 24/8/89) and there was speculation that it would become the ‘tinderbox’ which would set the rest of the country alight (Star 29/8/89). The security forces responded with a full range of repressive measures, and the wave of shootings and detentions which accompanied the protests were ultimately to provide a major setback to efforts of the new president, F.W. de Klerk, to present himself as an enlightened leader. In a surprising about-face, de Klerk sanctioned a planned march in central Cape Town to protest against police action. On 13 September 1989, 30,000 people of all races marched peacefully through the streets of central Cape Town behind the ANC flag, in the first legal demonstration of its kind (Cape Times 13/9/89). The Cape Town City Council mayor and most of the councillors led the march. Similar large-scale, government-sanctioned marches followed in the other major cities and smaller towns: the country had taken a decisive step towards political transition.

By late 1989 therefore, the government was challenged but not fundamentally threatened. Marais (1998) points out that the security apparatus and the military remained relatively intact, and that the ruling party had the support of large sections of business. It was very evident, however, that the situation was not a stable one. The onset of severe recession in early 1989 made urban infra-structural reform efforts more and more difficult, and fuelled the discontent of both workers and business. The rent and services payment boycott in the townships had proved particularly successful and services and administration in many townships were in a state of collapse. Occupants of the rapidly growing informal settlements of Cape Town had been concerned primarily with internal conflicts during 1989. This, largely, had taken the form of battles between Comrades – those aligned to the ANC – and warlords, traditional and politically conservative, sometimes self-appointed leaders, ruling often with tacit government support. But these areas too were showing signs of increasing political cohesion, as well as a tendency to voice their grievances outside government offices in central Cape Town: a march on the Provincial Administration days before the general election had presented demands for an end to forced removals, and the delivery of housing and services ‘on our present land’ (Cape Times 1/9/89). It was in these uncertain times, and in the context of growing pressure for the accommodation of African people within the metropolitan area, that the metropolitan planning authority of Cape Town turned its attention to the future of the city.

The battle of the spatial models: Cape Town as the ‘multi-nodal’ city

The group of planners who met on 16 June 1989 saw themselves as continuing the work of an earlier, 1988, committee which had met under the auspices of METPLAN at the offices of the Cape Town City Council. This earlier committee (the METPLAN Sub-committee Investigating Land for Future Housing for the Low-Income Group) had been set up in response to the 1986 government White Paper on urbanization, which had advised local authorities to think ahead on the issue of low income settlement. This issue had been a pressing one. The idea that racial groups should be spatially separated within urban areas was certainly being challenged on the ground, but was nonetheless still officially enshrined in the legislation of the government of the day. With influx control having been scrapped in 1986, and an expected rapid rise in the rate of African urbanization, it would need forward planning to ensure that new African urbanites were accommodated on land in a way which conformed with the principles of ‘separate development’.

By initiating an investigation into future land for settlement in Cape Town, METPLAN had opened up an important opportunity, and that was to challenge the official statutory Guide Plans for Cape Town – the planning instrument through which central government controlled urban settlement. There had been widespread recognition at this stage that the Guide Plan was outdated. Drawn up as a draft in 1984 (prior to the scrapping of influx control) the Guide Plan committee had simply not met since, and the approval of the draft plan in 1988 was probably no more than an attempt to keep up the appearance of central government planning control. As Theunissen, then a member of the METPLAN sub-committee, explained: ‘We were in injury time. Things were changing very fast and we had to fill the gap’ (Interview 1 1998).

The Guide Plan for the Cape Peninsula (Department ...