1

REFLECTIONS ON MASK AND CARNIVAL

Efrat Tseëlon

A society which believes it has dispensed with masks can only be a society in which masks, more powerful than ever before, the better to deceive men, will themselves be masked.

(Claude Lévi-Strauss, 1961, p. 20)

Covering the human face is as old as humankind. Evidence of the practice has been found in the artefacts, literature and lore of every society. Be it playful as in Halloween children’s parties or serious as in religious ceremonies, based on tradition or myth, democratically open or exclusively guarded – some form of masking has been known in every culture ranging from antiquity to the present, and from tribal cultures to the late capitalist West. Masks are made and used in various religious ceremonial cycles or events performed in association with numerous events: rites of initiation, rites of passage, mortuary rites, celebrations of the agricultural cycle, ritualised healing, warding off danger, parties and festivities. It is generally considered that masks are a type of artefact existing in cultures which practice magico-ritual activity (sometimes developing into a theatrical form). In Europe dressing up and the wearing of masks has been associated with the celebration of festivals since Roman Saturnalia, through medieval Carnival, up to eighteenth-century Masquerades.

Masks may seem emblematic: meaningful even when abstracted from their appropriate cultural setting. Gregor (1968) and Napier (1986), who have studied the anthropological literature, point to the mask’s common association with transformation and categorical change (represented, for example, in initiation rites, mourning rites, annual and seasonal changes, impersonation of animals, ancestors and deities). It applies to all masks used in ritual, theatre or carnival, even in sexual perversions. In spite of the evidence and the argument in favour of the universality of the mask, the meaning of masks is contextually bound and depends on use. Lévi-Strauss (1983) suggests that masks cannot be interpreted semantically outside their ‘transformation set’, whose lines and colours they echo. The reason is that masks are ‘linked to myths whose objective is to explain its legendary or supernatural origin and to lay the foundation for its role in ritual, in the economy, and in the society’. Thus, masking is not just about certain kinds of artefact: it is a cultural institution embedded in knowledge, traditions, beliefs and practices (cf., Mack, 1994a for an exhaustive collection). What is the appeal of mask and masquerade?

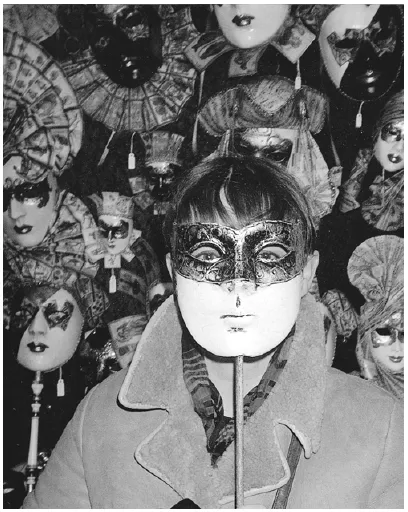

Plate 1.1 Mask shop in Venice. The masked mask sustains the illusion that whatever is deeper is somehow more true.

Source: Photo by the author.

Mask and death

We respond to the mask with a mixture of fascination and avoidance. We regard mime artists as reaching perfection when their pale made-up faces appear like masks and their gestures mimic a clockwork doll. But we admire dolls for their capacity to look like a real baby.

We want to speak to the mask because it is like us, but it responds with strangeness because it is not like us (Raz, 1995). Like the uncanny, it is familiar and unfamiliar simultaneously. The mask stands in an intermediary position between different worlds. Its embodiment of the fragile dividing line between concealment and revelation, truth and artifice, natural and supernatural, life and death is a potent source of the mask’s metaphysical power. The earliest masks have funerary associations. Mummy masks represented the deceased in the divine state they aspired to attain after death. The mummy masks first appeared in Egypt at the beginning of the second millennium BCE in Egypt, but their precursors can be recognised in burials dating back to the Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BCE) (Taylor, 1994). They had a major influence on the development of the anthropoids (human-like burial coffins decorated with clay funerary masks depicting an idealised face of the deceased). Those were widely used by Egyptian and Philistine civilisations from the Late Bronze Age (thirteen centuries BCE) (Dothan, 1982; Ornan, 1986; Ziffer, 1992). Golden death masks which are modelled on the faces of the deceased were found in the Cretan-Mycenaean age (second millennium BCE). Death masks were also involved in a Roman ritual tradition. When a member of the noble families died, a wax model was cast from his face to be worn by a person impersonating him at the funeral. The earliest evidence of masquerade in Mesoamerica (Mexico and Olmec civilisation) dates back to the middle pre-classic period (first millennium BCE). The Maya masks have mortuary or underworld associations. The Aztecs cremated their priests and rulers with burial masks representing deities with whom the ruler was affiliated (Shelton, 1994). In the Andes, masks were widely used to cover the faces of the dead. The ancient Peruvians (c. 500 BCE) placed a rude wooden image, usually fashioned when the person was still alive, upon the case in which the body was mummified, and in Melanesia the skull itself served as a mask during the sacred dances (Eliade, 1990). In Europe death masks became a widespread practice by the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Ariès, 1981). The mask, observes Sorell, ‘truly reflected the mystery of being which is the other side of the mystery of death’ (1973, p. 11). Indeed, from its origins in death it moved to the heart of life. In Western history the mask moved from the ritual to the theatre and ultimately to the streets. It appeared first in Dionysian festivities of antiquity and then, in direct descent from these, in the carnivalesque manifestations of the Christian era.

The mask is simultaneously animated and inanimate, living and dead: an expressionless mass transformed into expressive being. On its own it is a lifeless piece of matter, like the marionette without the puppeteer. But as soon as the mask is worn, or the marionette is pulled on a string, they come to life. Human interaction infuses them with spirit. The effect of the mask on the wearer is a well-known phenomenon in theatre and ritual: the wearer wishes to be identified with the mask they wear (Gregor, 1968). This is evidenced from ancient ceremonial masks as well as contemporary ones. The complete identification with the mask is what relates it to its very origins – in animal cults. In totemic cultures the earlier masks depicted animals. They were believed to have demonic power. These powers are then transferred to the mask. The masked man who impersonates the spirit truly believes himself to possess its demonic powers (Sorell, 1973, p. 8). Masks were believed to be inhabited by spirits, but also to be the means of driving them away. Thus, animal masks were used in mediating communication with supernatural forces for the purpose of securing an abundance of crops, preventing illness, curing disease, succeeding in war or hunt, and expelling evil spirits.

Plate 1.2 A mime artist in the Venice carnival. It takes only a coat of paint to transform a human face into a mask-like face.

Source:Photo by the author.

Mask and face

Its proximity to the face creates a peculiar relationship between the mask and the face. When the face is covered, awareness shifts to the body and different registers are used. The lifelessness of any mask becomes strangely animated when the body moves. This is obvious enough when the mask is expressive, as are the Trestle theatre giant-size masks, but it is also the case when the mask is inexpressive, as are the Noh theatre masks (see Plate 1.3). The masks of the Japanese Noh theatre are generally neutral in expression. Within a 600 year unbroken Noh tradition – where every movement is highly controlled and limited, no editing or adaptation is permitted and an actor has no liberty of physical expression – it is the skill of the actor that brings the mask to life. The actor has to learn to express variations in feeling through subtle changes in his physical movements, and by symbolic representation. It is the actor’s internal creative force which creates the intensity of his expression (Sekine and Murray, 1990).

This creative force is also shared by children, who are capable of being so absorbed in the mask as to bring out a character from even an inexpressive mask. Face masks have generated explanations about the psycho-philosophical properties of masks, and their power to transform and liberate the creative imagination of players donning them (Richards and Richards, 1990). Peter Brook observed that ‘The actor, having put the mask on, is sufficiently in the character that if someone unexpectedly offered him a cup of tea, whatever response he makes is totally that of that type, not in a schematic sense but in the essential sense’ (Brook, 1987, p. 221). This is characteristically typical of the actor of the Noh theatre who first dons the costume and sits in front of a mirror, studying the mask and ‘becoming one with the character he is about to perform’. When he wears the mask he stands in front of a mirror ‘letting the mask take over his own personality’ (Irvine, 1994). The founders of the Ophboom theatre, a contemporary Commedia dell’arte group formed in 1991 (modelled on the spirit of the original sixteenth-century Italian improvisational dramatic performance) describe this as ‘the madness of the mask’. ‘Using masks as a performer alienates one from one’s own body and this alienation frees the mind from normal, rational thought, until the performer becomes as it were, possessed by the mask’ (Beale and Gayton, 1998, p. 176).

Each mask generates its own characteristic repertoire of gestures and poses. Kobi Versano recounted to me a North-African folk story he heard from his grandfather about the string instrument player whose range of tunes became more and more limited with every string that expired. Until in the end, when the last one expired he was finally liberated from the constraints of the medium and could play any tune in the world. Paradoxically it is the expressive which is pre-determined and limited. And it is the expressionless which is the most expressive as it brings out multiple potentials.

This, of course, is what links masks to imagination. The mask, says Gregor, who has studied many masks all over the world, stands for the plenitude of creative power. A related motif runs through the fantastic tales of the Danish writer Isak Dinesen. Contrary to the bourgeois attitude which is preoccupied with questions of true identity and self-actualisation, Dinesen’s aristocratic view places a high value on artistic creativity, adventure, dreams and imagination, not on truth. It is expressed, for example, in the words of the character in The Deluge of Norderney Miss nat-og-dag (night and day) who challenges the valet’s idea that god wants the truth from us: ‘why, he knows it already, and may even have found it a little bit dull. Truth is for tailors and shoemakers’ (Dinesen, 1963, p. 141). Instead, she maintains, god prefers the masquerade. Kasparson observes that the mask is not all deception in that it reveals something of the spirit which life conventions conceal. Therefore, god might say that the person is known by the mask that they wear (Johannesson, 1961). One can detect here the influence of Nietzsche, who regards the mask as a device for releasing a power just as valuable as truth: ‘it could be possible that a higher and more fundamental value for life might have to be ascribed to appearance, to the will to deception, to selfishness and to appetite’ (1987, p. 16). Yet there is not only deceit behind the mask, but also necessary cunning. Since every deep spirit is bound to be misunderstood, a mask is continuously growing around it, due to the shallow interpretation people make of its word and deed. Hence ‘everything profound loves the mask’ (ibid., p. 51).

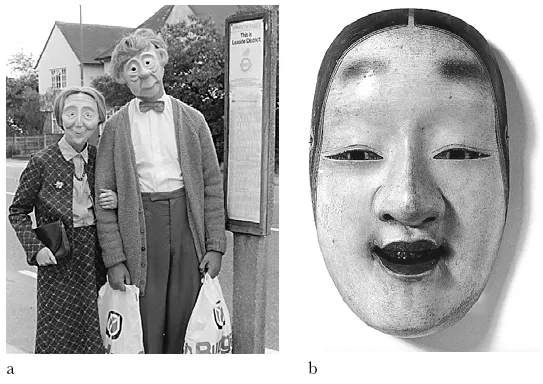

Plate 1.3 The Trestle Theatre mask’s expressive potential is limited by the emotion inscribed on it. The Japanese Noh mask is a neutral mask, hence capable of expressing any emotion. Both come to life only through the actor’s body. a) Trestle Theatre masks in the production Top Storey. b) A Japanese Noh mask.

Source: a) Courtesy of Trestle Theatre, b) Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Identity

Already its earliest sources in Western civilisation mark the mask as closely connected to the notion of the person. The Romans borrowed the concept of mask from the Greeks via the Etruscan civilisation where it represented face, or person. Mauss sees the human actor who is a carrier of roles, rights and responsibilities as a social creation, hence transient and changing (e.g. for the Hellenes the obverse of the person is the slave, for the Christian the unsouled, and for the Kantian the non-rational (Rorty, 1987)). Mauss argues that the idea of the individual is unique to Western thought, and attributes to the Greek roots of our civilisation a notion of the actor behind the mask. Originating in the masked drama of Athenian theatre, mask was used as identification of character, not as a deception or disguise. Mask and face were interchangeable (Jenkins, 1994).

The idea of the individual was later translated into the idea of the soul. From the Greeks the idea travelled to the pro-Hellenic Jewish sects of the Pharisees and the Essenes in the first century BCE and later on to the sect which became Christianity (Dimont, 1994). The idea of the individual as a locus of personal accountability and moral obligation has always been at the heart of Judaism, reinforced by the sayings of Isaiah and Ezekiel (Johnson 1987). But it was Protestant Christianity which made the soul, a metaphysical category (Hollis, 1985) and a touchstone of its faith . The Roman ‘person’ was a judicial category more than a name or the right to a role and a ritual mask. The Stoics added moral obligations to the personal rights. From the second century BCE the word persona (Latin for mask) acquired the sense of an image which signifies a person. It contained a notion of artifice but also a notion of one’s role, character, ‘true’ face (Mauss, 1979).

Contemporary approaches to personhood talk about identity. Identity is a construction by which a person is known, and disguise is almost a design feature of that construction. The philosophy of the mask represents two approaches to identity. One assumes the authenticity of the self (that the mask – sometimes – covers). The other approach maintains that through a multitude of authentic manifestations the mask reveals the multiplicity of our identities. Of course, the preoccupation with selves and identities is uniquely Western. It is an epistemology based on a belief in a single reality and unity of experience. The concept of identity, however, is not exhausted within the parameters of authentic and inauthentic or single and multiple. Other approaches introduce notions of reality and fantasy, as well as truth and fiction. The traditional mask, says Peter Brook, provides a hiding space. This fact ‘makes it unnecessary for you to hide. Because there is a greater security, you can take greater risks; and because here it is not you, and therefore everything about you is hidden, you can let yourself appear ‘ (1987, p. 231). In contrast, Sorrell regards the mask as an imaginary shield that protects us against reality, a symbol of escape into a make-believe reality ‘the persona is the mask which protects us not only against the other people behind their masks, but also against our own real self ’ (1973, p. 13); ‘the mask contains the magic of illusion without which man is unable to live’ (ibid., p. 15). For Yeats the retreat from the reality self is not to a fantasy creation but to an heroic ideal one. The antithesis of conventionality, he sees the mask as a voluntary constraint or discipline imposed on the self in order to achieve victory over circumstances (1962, p. 108). For him the mask signifies ‘active virtue, as distinguished from the passive acceptance of a code, [it] is therefore theatrical, consciously dramatic’ (1972, p. 151).

Psychoanalytic reality, for example, created tolerance to various states of mind, and levels of existence. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde need not be an expression of a pathological personality. Psychoanalitically speaking, identity is an unconscious fantasy, an illusion of wholeness that covers splits. More precisely it has two meanings: the dynamics of the integrative effo...