eBook - ePub

The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt

A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh's Workforce

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt

A Modern Investigation of Pharaoh's Workforce

About this book

In Rosalie David's hands, the Egyptian builders of the pyramids are revealed as simple people, leading ordinary lives while they are engaged on building the great tomb for a Pharoah. This is an engrossing detective story, bringing to the general reader a fascinating picture of a special community that lived in Egypt and built one of the pyramids, some four thousand years ago.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt by Dr A Rosalie David,Rosalie David in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE BACKGROUND

CHAPTER 1

The Geography and Historical Background

The geography of Egypt

Every civilisation reflects, to some degree, the influence of its environment. Egypt is a country where, perhaps more than most, the physical and natural features provide a dramatic and contrasting setting for human events. It would be difficult to reside in Egypt and remain unaffected by the natural forces and their cycles. In antiquity, as now, the two great life-giving forces were the Nile and the sun, and in their religious beliefs the Egyptians recognised the omnipotence of these, as well as the existence of the other natural elements which shaped their world.

In the words of a Classical writer, Egypt is the ‘gift of the Nile’. The existence of the fertile areas has always been due to the natural phenomenon of the regular inundation of the river, for Egypt’s scanty and irregular rainfall would never have supplied sufficient water to support crops and animals. The Nile, Africa’s longest river, rises far to the south of Egypt, in the region of the Great Lakes near the equator. Known as Bahr el-Jebel (Mountain Nile) in its upper course, after its junction with the Bahr el-Ghazel it becomes the White Nile. In the highlands of Ethiopia, another river, the Blue Nile, rises in Lake Tana, and the Blue and White Niles join at Khartoum. From Khartoum to Aswan the river is now interrupted by a series of six cataracts. These are not waterfalls, but appear as scattered groups of rocks across the river which obstruct the stream, and at the Fourth, Second and First cataracts, interfere with navigation. Egypt begins at the First Cataract, and comprises the area between this natural barrier and the Mediterranean, some 965 km to the north. It was in the region of the northernmost cataracts that the Egyptians, from early times, subdued the local population, to gain access to the hard stone and gold supplies of Nubia.

Within Egypt, the Nile follows a course which divides into two regions. The Nile Valley, a passage which the river has forced through the desert, runs from Aswan to just below modern Cairo, a distance of some 804 km. The scenery along this valley varies from steep rocky cliffs which rise up on either side of the river, and then give way to the encroaching deserts, to flat, cultivated plains, with lush vegetation which, again, in the far distance, succumb to the desert. This cultivated area, wrung from the desert by the irrigation of the land with the Nile floods, varies in width; in parts, the Nile Valley is between twelve and six miles wide, but elsewhere, the cliffs hug the edges of the river and there is no cultivatable land. Nowhere in Egypt is the traveller more aware of the significance of the river’s life-force, for here there is virtually no rainfall. The sun is always present, and without the Nile, this region would be desert, like the surrounding area.

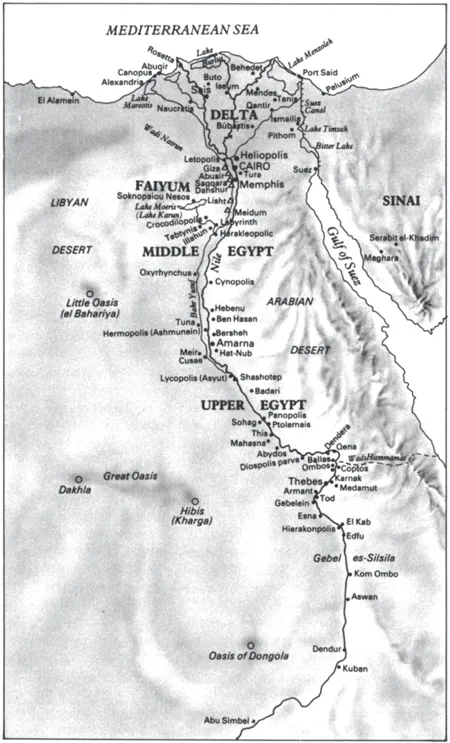

The ancient Egyptians recognised the geographical facts and divided their country into two regions. In earliest times, this was a political as well as a geographical reality, but even after the unification of the country, the concept of ‘Two Lands’ was still present. To them, the Nile Valley was ‘Upper Egypt’, whereas the northern area, the Delta, was ‘Lower Egypt’.

Today, the modern capital of Egypt, Cairo, stands at the apex of the Delta. In antiquity, the ancient capital of Memphis lay a few miles south, and from here there was a marked change in the Nile and its surrounding countryside. Here, the river fans out into a delta nearly one hundred miles long; through the two main branches at Rosetta in the west and Damietta in the east, it finally flows into the Mediterranean. The Delta forms a flat, low-lying plain, scored by the Nile’s main and lesser branches; at its widest, northern perimeter, it spreads out over some two hundred miles. However, despite the considerable area of watered land in this region, much of the Delta is marshy or water-logged and cannot be cultivated. Here in antiquity, the nobility and courtiers enjoyed favourite outdoor pastimes of fishing and fowling in the marshes. The climate in the north also differs from that of Upper Egypt, for the temperatures are more moderate and there is some rainfall.

The ‘Two Lands’ were therefore distinct regions, but were nevertheless interdependent, joined together by the unifying force of the Nile. However, their geographical features imposed different attitudes on their inhabitants. Lower Egypt, closest to the Mediterranean, looked towards the other countries to the north, and was more readily receptive of influences from outside, becoming a centre for the cross-currents of the politics and culture of the ancient world. Upper Egypt, encapsulated by the deserts and bordered on the south by the land of Nubia, was more isolated from new ideas and influences. The contrast between the Two Lands can be seen not only in the geographical and environmental features, but in the distinctive art schools which emerged and even in the physique of the people. The northerners tended to be more stockily built, with lighter skins, while the southerners displayed something of the angularity evident in the southern school of art. However, these are broad generalisations, for Egypt remained a strongly unified country; at different periods, the capital moved from one region to another, and with it, the courtiers, officials, craftsmen, and workforce associated with the requirements of a great city; and the art followed the same broad traditional principles in both north and south, so that today only an experienced eye can detect differences in the ancient regional art styles.

FIGURE 1 Map of Egypt (Taken from G.Posener (ed.), A Dictionary of Egyptian Civilisation.

It was the Nile however which enabled the Egyptians to cultivate crops and to rear animals, and indeed to develop their remarkable civilisation. Rain in Upper Egypt was the exception, and the infrequent, short and violent rainbursts could often bring damage; these were regarded as evil rather than beneficent events. In the Delta also, only the northernmost area benefited from the wintry rains of the Mediterranean. It was the annual inundation of the Nile which brought life to the parched land.

This was the most important natural event of the year, and inevitably became the focus of religious attention. The annual rains in tropical Africa caused the waters of the Blue Nile to swell; in Egypt, this eventually had the effect of causing the river to flood its banks, and spread out over the fields, carrying with it the rich, black mud which was deposited on the land. It was this silt and the people’s management of the water which enabled the Egyptians to grow and cultivate crops. The rise of the river was first noticeable at Aswan in late June; by July, the muddy silt began to arrive. The swelling flood would cover the surrounding fields, and if it breached the dykes, would submerge the fields and villages to a depth of several feet. The flood finally reached the area near Cairo at the end of September, and the waters would then gradually recede, with the river contained within its banks by October and reaching its lowest level in the following April. Thus, the countryside presented great extremes—for part of the year, the villages and palm trees could be marooned like islands in the expanse of floodwater; by the end of the cycle, the earth would be parched and cracked, awaiting the new, life-giving waters of the next inundation.

However, the Nile’s gift was variable and although it rose unfailingly, the height of the inundation fluctuated. A Nile which was too high would flood the land and bring devastation and the ruination of the crops; towns, villages and houses could also be destroyed, with the consequent and considerable loss of life. On the other hand, a low Nile would bring famine. The erratic nature of the inundation was a constant threat to the safety and prosperity of the people, and although the Egyptians showed great awareness of their dependence on the inundation in their religious literature, they were also constantly concerned that the inundation should not be exceptional. Indeed, it is not surprising that moderation and balance were amongst their most highly valued concepts.

In addition to their religious observances, from earliest times, they took practical measures to control and regulate the Nile waters. Started in the predynastic period, their irrigation system evolved a pattern whereby the land was divided up into sections of varying sizes, each being enclosed by strong earth banks. These banks were arranged on a chequerboard system, with long banks running parallel to the river, and another series running across them, from the river to the desert edge. At the inundation, the water was let into the banked sections through canals, and was held there while the silt settled. Once the river had fallen, the water was drained off, and the ploughing and sowing began. This system provided Egypt with rich agricultural land, and the need for such a system was also probably responsible for the early centralisation and organisation of the country.

The interdependence of physically isolated village communities on the all-important joint project of constructing, extending and maintaining an irrigation system gave the people an awareness of the need to co-operate and an acceptance of a strong centralised state. Dykes and dams were built, canals were dug and the system was maintained with the active support of the first kings. Today, the advent of a successful harvest is no longer dependent on nature, and on the petitions addressed to the Nile god, Hapy, and to Osiris, the god of vegetation and rebirth. Modern technology has led to the building of dams at certain points on the river, enabling the volume of water to be held back and supplied for irrigation as required, through a series of canals.

The physical division of Egypt into northern and southern regions is not the only geographical distinction which the Egyptians recognised. It is still possible today to stand with one foot in the desert and one in the cultivation, along the clearly defined line of demarcation between these two areas. For the Egyptians, the cultivated area represented life, fertility and safety; here, with assiduous husbandry, they could grow ample crops, and establish their communities. The name they gave to their whole country was ‘Kemet’, which means the ‘Black Land’. This referred to the cultivation, fertilised for countless years by the black mud of the inundation. Beyond this strip, however, lay the desert, stretching away to the horizon under the glaring sun, a place of death and terror to the Egyptians. They gave this the name of ‘Deshret’, meaning ‘Red Land’, because of the colour of the rocks and the sand. These two regions symbolised life and death, and probably influenced some of their most basic religious ideas.

The other most important natural life-force was of course the sun. The Egyptians acknowledged this as the creative force and sustainer of life, and worshipped it under several names as a god; however, Rec was the name by which the solar deity was continuously and most frequently known.

The two great life-forces of sun and Nile had much in common. Both expressed, in their natural cycles, patterns of life, death and rebirth. The sun rose every morning and set at night, to reappear unfailingly on the horizon; the Nile annually imparted its gift of water, so that the life, death and rebirth of the countryside was vividly experienced. It has been suggested that this regular environmental pattern impressed itself so clearly on the Egyptian consciousness that they transferred the concept of life, death and rebirth, seen in natural cycles, to the human experience. From their earliest development, it seems that they believed in the continued existence of the individual—his rebirth—after death, and the concept of eternity remained a constant feature of their religious and funerary ideas. Although the supposed exact location of this continued existence varied in the different historical periods and according to the individual’s social status, all Egyptians believed in some kind of afterlife and, for those who could afford it, elaborate preparations of the tomb and associated funerary equipment were made, to facilitate the deceased’s journey into the next world. Both the gods associated with these life-forces—Rec as the solar god, and Osiris, the god who symbolised vegetation and was king of the underworld by virtue of his own resurrection from the dead—promised regeneration and eternity to their followers.

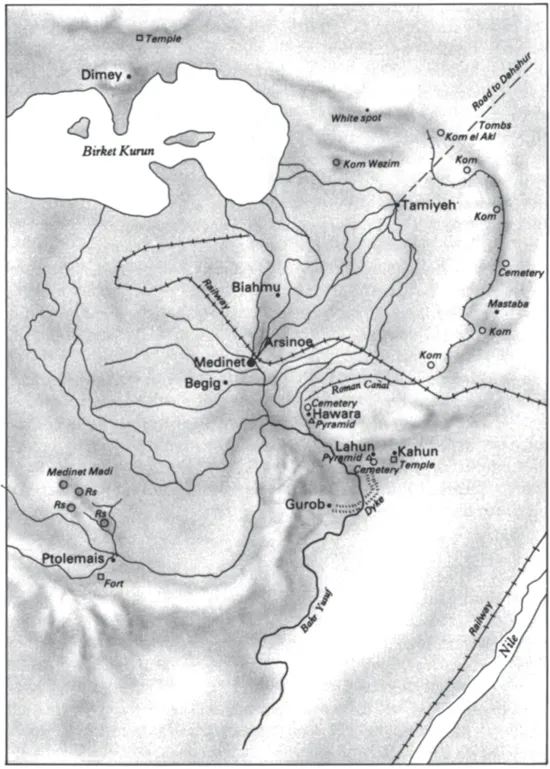

FIGURE 2 Map of the Fayoum oasis, showing location of Kahun, Lahun pyramid and Gurob. (From W.M.F.Petrie, Illahun, Kahun & Gurob, pl. XXX).

It was possible for the often unique ideas which distinguished the Egyptian civilisation to flourish over many centuries and to develop largely unaffected by outside influences, because of the geographical situation of the country. A glance at a map of Egypt will immediately reveal the importance of its natural barriers. In antiquity, these were of more significance than they are today, for they encapsulated Egypt and buffered it against all invaders, so that, unlike many other areas, in the earlier times at least, Egypt was not subjected to continuous waves of conquerors. To the north, there lies the Mediterranean and to the south, the African hinterland; on the east there is the eastern desert and the Red Sea, while to the west, with its seemingly endless desolate hills, the Libyan desert stretches out. Here, in an otherwise waterless expanse, there runs an irregular chain of oases, scattered roughly parallel to the river. The largest ‘oasis’ (although, strictly speaking, it is not a true oasis) is the Fayoum, a depression in the desert, into which runs a minor channel, some 321 km long, known as the ‘Bahr Yusef’ (Joseph’s river). This channel leaves the main stream of the Nile west of the river near the modern town of Assiut. It was here, in the Fayoum, that the community of Kahun lived some 4,000 years ago. But before returning to consider this area in more detail, it is necessary to examine the historical events which led the kings of the 12th Dynasty to select the Fayoum as their centre.

The historical background

Most studies of ancient Egyptian history cover the period from c. 3100 BC down to the conquest of the country by the Macedonian king, Alexander the Great, in 332 BC. However, the so-called Predynastic Period (5000 BC—c. 3100 BC) laid the foundations for much of the subsequent history, and the Graeco-Roman Period (332 BC—AD 641) illustrated the final decline and disappearance of many of those beliefs and representations that we would describe as ‘ancient Egyptian’.

In the Palaeolithic Period, the Nile valley was virtually uninhabitable either because for three months of every year it was under water, or because it was otherwise covered with thick vegetation and supported teeming wildlife. The earliest inhabitants were hunters who lived on the desert spurs and made forays into the valley to pursue their game.

However, as the floor of the valley became drier, the people began to move down and to live together in settlements. Some time between 5200 BC and 4000 BC farming developed, and the people began to support themselves by growing grain, domesticating animals, and continuing to pursue, increasingly infrequently, the wild animals. Although these peoples fall into two broad geographical groups—one in the Delta and one in the Nile Valley—there are general features and patterns of development which, as Neolithic communities, they have in common. Much of our present knowledge of this era has been obtained from the remarkable discoveries and pioneering studies of William Flinders Petrie, the excavator of Kahun, and, with subsequent research, it has been possible to establish, for Upper Egypt, a well-established chronological sequence of divisions within the Predynastic Period, which lead up to the 1st Dynasty (c. 3100 BC). These are known as the Tasian, Badarian, Nagada I and Nagada II periods. In the Tasian and Badarian periods, the people practised mixed farming but still lived mainly on the desert spurs overlooking the Valley. However, in the Nagada I period, they settled along the Valley in fairly isolated communities. By the Nagada II period, there was increased contact with other parts of the Near East, and gradually, villages and towns in the north and south of Egypt developed into two distinct kingdoms, one in the Delta, known as the ‘Red Land’, and one in Upper Egypt, known as the ‘White Land’. Each had its own king, who was the most powerful of the local chieftains in the area. It was the unification by a southern ruler of these two kingdoms—the ‘Two Lands’—in c. 3100 BC that ushered in the historical period, with the establishment of the 1st Dynasty. The growing political awareness and development in these predynastic times was mirrored in a major advancement in the technological, artistic and religious spheres, and the artefacts, especially the painted pottery and metalwork, show an increasing ability to handle materials.

However, it was the unification of Egypt by King Menes who became the first king of the 1st Dynasty that marks the beginning of Egyptian history. The basis of our chronology for the historical period (c. 3100–332 BC) rests upon the work of Manetho, a learned priest who lived in the reigns of the first two Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt (323–245 BC). He wrote a history of Egypt (in Greek) around 250 BC and prepared a chronicle of Egyptian rulers, dividing them into thirty-one dynasties. There seems to be no clear-cut definition of a dynasty. Although some contain rulers related to each other by family ties, and the end of a dynasty can be marked by a change of family (brought about by the end of one line, or by wilful seizure of power by another faction), in other cases, family groups span more than one dynasty and the change of dynasty was brought about peacefully.

Modern research has shown that Manetho’s record (preserved imperfectly in the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus (AD 79) and of a Christian chronographer, Sextus Julius Africanus (early third century AD) is not always entirely accurate. However, as a member of the priesthood, he undoubtedly had access to original source material in the ancient King Lists and records kept in the temples, and his work remains the basis of our chronology. Today, his dynasties are usually grouped together by Egyptologists into a number of major periods, distinguished by political, social and religious developments. Thus, we find that the Archaic Period (1st and 2nd Dynasties) is followed by the Old Kingdom (3rd to 6th Dynasties). This is followed by the First Intermediate Period (7th to llth Dynasties), and then the Middle Kingdom (12th Dynasty). The Second Intermediate Period (13th to 17th Dynasties) leads on to the New Kingdom (18th to 20th Dynasties), which in turn gives way to the Third Intermediate Period (21st to 25th Dynasties). The Late Period (26th to 31st Dynasties) is followed by the Graeco-Roman Period. The three greatest periods were the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms, which were interspersed by times of internal dissension. The story of Kahun falls into the Middle Kingdom (1991–1786 BC), although some of the threads must be traced to the preceding and subsequent periods.

King Menes and his immediate successors established the foundations of a stable and unified kingdom. Untroubled by any major internal or external conflicts, Egypt, during the Archaic Period, was able to develop technological skills which were to lead to the great advances of the Old Kingdom. Central to their beliefs was the idea that the dead, in preparation for an afterlife, needed a tomb (a ‘house’ for eternity), and food, clothing, furniture, and other essential equipment. It was also necessary for the body of the deceased to be preserved in as lifelike a state as possible, to enable his spirit to re-enter the body and to partake of the essence of the food offerings either placed in the tomb or subsequently brought to the associated funerary chapel by the dead person’s relatives.

At first, such elaborate funerary preparations were only made for the king, and his great courtiers. Other people were simply buried in the sand in shallow graves, surrounded by their few personal possessions. However, the funerary preparations of the few, and especially of the king, were so important that considerable resources were devoted to achieving secure and increasingly elaborate burial places. The technical advances made in Egypt at this early period were primarily directed to this end, and only gradually filtered through to benefit the burials at other levels of society, and also the general conditions of daily existence.

Thus in the earliest dynasties, we see the development of a type of tomb which is known today as a ‘mastaba’, because its superstructure resembles the shape of a bench, for which ‘mastaba’ is the modern Arabic word. From the 1st Dynasty onwards, kings and nobles were buried in mastabas, in the substructure below ground. Built of mud-brick, the superstructure was rectangular and divided internally into many cells or chambers, in which the domestic and other equipment for the next life was stored. This structure was almost certainly regarded as a house, embodying the same elements as a dwelling for the living, but to be occupied by the dead owner’s spirit. The substructure incorporated the burial pit and was theoretically protected from robbers and animals by the superstructure. However, the mastaba afforded only ineffectual protection for the body, and in the 2nd and 3rd Dynasties the storage area was transferred below ground, ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE BACKGROUND

- PART II: THE TOWN OF KAHUN

- PART III: THE INVESTIGATION

- CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY