- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evolutionary Explanations of Human Behaviour

About this book

In recent years, a new discipline has arisen that argues human behaviour can be understood in terms of evolutionary processes. Evolutionary Explanations of Human Behaviour is an introductory level book covering evolutionary psychology, this new and controversial field. The book deals with three main areas: human reproductive behaviour, evolutionary explanations of mental disorders and the evolution of intelligence and the brain. The book is particularly suitable for the AQA-A A2 syllabus, but will also be of interest to undergraduates studying evolutionary psychology for the first time and anyone with a general interest in this new discipline.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evolutionary Explanations of Human Behaviour by John H. Cartwright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Introduction

Psychology and the theory of evolution

The mechanism of Darwinian evolution by natural selection

The nature of evolutionary adaptations

Why apples are sweet: ultimate and proximate explanations in psychology

Case study: the avoidance of incest

Summary

Psychology and the theory of evolution

When Darwin published his Origin of Species in 1859, he was confident that in time it would supply a new basis for all the life sciences. Towards the end of the Origin he wrote:

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history. (Darwin, 1859, p. 458)

Darwin was perhaps overoptimistic, for despite some early work by William James in America it was not until the 1970s that the evolutionary approach to human behaviour in the form of sociobiology and what was to become evolutionary psychology took root. For much of the twentieth century psychologists failed to follow Darwin’s lead and either ignored or misinterpreted Darwin. Many psychologists and biologists, and I count myself one of them, now think that it is time for psychology once again to re-establish links with the central paradigm that underlies all of the life sciences: the theory of evolution by natural selection. I will leave it up to you, the student, to read this book and decide if you think psychology has anything to learn from Darwinism.

The mechanism of Darwinian evolution by natural selection

The American philosopher of science, Daniel Dennett, once said that ‘If I were to give an award for the best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else’ (Dennett, 1995). As we grasp the awesome significance of Darwinian ideas it is hard not to share Dennett’s enthusiasm. In the theory of evolution we have a theory as to where life came from, why life exists at all and how the construction and behaviour of organisms serve their survival.

The essential features of Darwinism can be summarised as a series of statements about the characteristics of living things:

- Based on such characteristics as anatomy, physiology and behaviour, individual animals can be grouped into species. A species is not entirely an artificial construct since members of the same species, if they reproduce sexually, can, by definition, breed with each other to produce fertile offspring. Using this criterion, for example, all humans belong to the same species: Homo sapiens.

- Within a given species or population variation exists; individuals are not identical and differ in physical and behavioural characteristics.

- Many physical and behavioural traits are expressions of information to be found in the genome of individuals. The genome consists of strands of DNA carrying information in the form of a molecular code. Individuals inherit their DNA from their parents (50% from each) and pass their own DNA on to their offspring.

- In sexually reproducing species, such as humans, offspring are not identical to their parents. This is because each new individual contains a whole mixture of genes from each parent in a new combination. Some of these genes may not even have been switched on in our parents. Apart from rare cases of identical twins, we are all genetically unique. In addition, variation is enriched by the occurrence of spontaneous but random novelty. Genes often suffer damage or mutations and a feature may appear that was not present in previous generations or present to a different degree. Most mutations are harmful and all animals have chemical screening techniques to root them out. Occasionally, however, such changes may bring about some benefit.

- Resources required by organisms to thrive and reproduce are limited. Competition must inevitably arise and some organisms will leave fewer offspring than others will.

- Some variations will confer an advantage on their possessors in terms of access to these resources and hence in terms of leaving offspring.

- Those variants that leave more offspring will tend to be preserved and gradually increase in frequency in the population. If the departure from the original ancestor is sufficiently radical, new species may form and natural selection will have brought about evolutionary change.

- As a consequence of natural selection, organisms will eventually become adapted to their environments and their mode of life in the broad sense of being well suited to the essential processes of life, such as obtaining food, avoiding predation, finding mates, competing with rivals for limited resources and so on. Organisms, through this process of adaptation, will look as if they were expertly designed for their activities.

To this we may now add specific expectations about the human body and mind: - Because of Darwinian evolution, both the human body and the mind can be expected to be structured in ways that helped our ancestors to survive and reproduce. Since hominids have been on the planet for about 5 million years the human body and mind should, by now, be well adapted for these purposes. Consequently, human behaviour, at least to the degree that it is under genetic influence, will be geared towards survival and ultimately reproductive success.

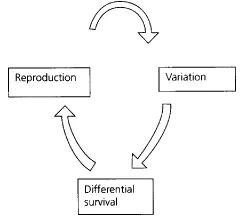

These ideas can be described schematically as a sort of cycle involving the birth and death of organisms, a Darwinian wheel of life (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 A Darwinian wheel of life. The birth and death of thousands of individual organisms result in gradual modification through differential survival. The result is the gradual formation of new species and, crucially for Darwinian psychology, the emergence of adaptations

In applying Darwinism to human behaviour, it is important to distinguish between genotype and phenotype. Your genotype consists of the set of genes that you inherited from your mother and father. Such genes contain the information needed by cells to carry out their functions of growth and reproduction. The information stored there, in concert with environmental influences when you were growing and those acting now, determines who you are. The finished product, yourself, is the phenotype. It is important to realise that the flow of information from the genes to the phenotype is one way. Your genes can influence your development, behaviour and personality, but you cannot alter the information stored in your genes. If, for example, you spend years of study learning Chinese, your offspring will not speak Chinese, nor, sadly, will they necessarily find it easier than you to learn Chinese. This is sometimes expressed abstractly in the rule that acquired characteristics cannot be inherited. The environment in whichan animal grows can influence the phenotype but not the messages found along its genes.

The nature of evolutionary adaptations

Movement around the Darwinian wheel of life (Figure 1.1) will result in organisms that are adapted to maximise their reproductive fitness. Fitness here refers to the special biological sense of being capable of leaving offspring. Organisms will behave so as to ensure that they reproduce successfully in competition with others. There is no special virtue or purpose in this; it is simply that organisms that, perhaps through chance genetic variation, were less skilled or earnest in this process have died out. It is a truism but worth repeating that none of us is descended from an infertile ancestor.

Figure 1.2 Photograph of Charles Darwin by Ernest Edwards, taken in about 1870

An important question to address when studying the evolution of human behaviour is the problem of whether behaviour will appear to be adapted to current conditions or to conditions in the past. A behavioural trait that we study now may have been shaped for some adaptive purpose long ago. The environment may have changed so that the adaptive significance of the trait under study is now not at all obvious; indeed, it may now even appear maladaptive. When human babies are born they have a strong clutching instinct and will grab fingers and other objects with remarkable strength. This may be a leftover from when to grab a mother’s fur helped reduce accidents from falling. It is not clear that it helps the newborn in contemporary culture.

The problem applies to other animals as well of course. When a hedgehog rolls up into a ball in the face of oncoming traffic this is no longer a sensible response to the threat from a predator. The problem is especially acute for humans, however, since over the last 10,000 years we have radically transformed the environment in which we live. We now daily encounter situations and challenges that were simply absent during the period when the human genome was moulded into its present form. It could be expected that we have adaptations for running, fighting, throwing things, weighing up rivals, securing alliances, finding and seducing mates, and making babies but not specifically for reading, driving cars, playing tennis, studying psychology or coping with jet-lag. Logically, any adaptation that we have now must have been shaped by the past. One crucial question therefore is whether the human psyche was designed specifically to cope with problems found in the environment of our evolutionary adaptation (EEA)—usually taken to be between 2 million and 40,000 years before the present—or whether our psyche is flexible enough to direct behaviours that still tend to increase our reproductive fitness in the contemporary world.

As an illustrative example, consider food preferences. Humans, and especially children, are strongly attracted to salty and fatty foods high in calories and sugars. Our taste buds were probably finely and appropriately adjusted for the Old Stone Age (roughly 200,000 to 10,000 years before the present) when such foods were in short supply and to receive a lot of pleasure from their consumption was a useful way to motivate us to search out more. Such tastes are now far from adaptive in an environment in developed countries where fast food high in salt, fat and processed carbohydrates can be bought cheaply, withdeleterious health consequences such as arteriosclerosis and tooth decay.

There is obviously some truth in this viewpoint, but it is also important to note that natural selection can shape how development and learning occur in relation to local environments. It follows that behaviour does not have to be forced into the category of ‘hard-wired’ mental tools designed for an ancient environment. Natural selection could have shaped our minds to behave in ways that increase our fitness under contemporary conditions. Symons (1992) criticised this latter approach, however, by remarking that if modern males really did behave so as to maximise fitness then ‘opportunities to make deposits in sperm banks would be immensely competitive…with the possibility of reverse embezzlement by male sperm bank officers an ever-present problem’.

The answer of course is that natural selection did not provide us with a vague fitness-increasing drive. The genes made sure that fitness maximisation was an unconscious urge—an urge that certainly must have predated consciousness. Like the heartbeat, it was too valuable to be placed under conscious control. Instead, males and females were provided with powerful sexual drives. Counting the size of the queue outside a sperm bank would be a fruitless way of assessing whether males pursue fitness-maximising strategies. Counting partners and real sexual opportunities, however, might be better. If sperm banks were set up to allow males to deposit sperm more naturally (in other words, through sexual intercourse) the queues would probably be longer.

Why apples are sweet: ultimate and proximate explanations in psychology

Consider the question ‘Why are apples sweet?’ and the type of answers we can give. A biochemist might reply that it is due to the shape of the sugar molecules of fructose and sucrose triggering a response on a taste bud receptor on the tongue. A neurobiologist (someone who studies the brain from a chemical and biochemical point of view) might complement this by locating the nerve pathways and the part of the brain that is activated when the sweet sensation is experienced. Both explanations are partial and fail to explain, for example, why humans find apples sweet but many other animals (such as cats) probably do not. What both the biochemist and the neurobiologist have done is toprovide proximate explanations or to reveal proximate mechanisms. In this context proximate means near to or immediate. The proximate cause of a heart attack, for example, may be reduced blood flow to the muscles of the heart. The ultimate cause may be poor diet, or stress or some genetic defect at birth. For the ultimate explanation of sweetness—sometimes called, rather confusingly for the student, functional—we need to dig deeper and call upon Darwinian psychology. The Darwinian or ultimate explanation would run something like this. Humans experience a sweet and pleasurable sensation on tasting apples because apples contain essential nutrients such as minerals and vitamin C. The pleasure experienced on eating provided the motivational stimulus for our remote ancestors to eat such foodstuffs; our ancestors that were disposed in this way to consume apples and other fruits thrived, whereas those that failed to consume them died out. The argument probably sounds a little pedantic but it is essential to grasp the logic of natural and sexual selection. We can now see why cats are not too fond of apples. Cats can manufacture their own vitamin C and consequently there is no real advantage to them in consuming fruit.

It is important to grasp that the genes that shape our taste bud circuits and other neural pathways are not striving to survive by ensuring that we obtain our essential nutrients; it is simply that those that dispose us to behave in certain ways do survive and others are lost, but the whole show is not going anywhere. We must also be wary of interpreting the word mechanism. In evolutionary psychology, the word mechanism is used as a shorthand for the series of neural circuits, mental dispositions and so on that promote certain types of behaviour. We should not think, however, that behaviour is simply mechanistic or that it is invariant and ‘hard-wired’. Hard-wiring may be suitable for ants but evolution gave up hard-wiring the higher mammals long ago. Our lives are too complex and we need to learn so much from experience that fixed patterns of behaviour would be unsuitable for us and unable to solve our survival problems. We need to weigh up evidence, evaluate alternatives and plan courses of action and all this requires some cognitive subtlety. Nevertheless, evolution has crafted our brains around the biological imperatives of survival and reproduction; we are inclined to make certain types of decisions, to find certain foods or people attractive. Despite our mental sophistication there are still those ‘murmurings within’ (to use a phrase of the American evolutionist David Barash) that structure our actions, behaviour and thoughts.

One awesome implication of Darwinism, that many find difficult to stomach, is that there is no ultimate purpose, design or destiny to the natural world. Natural selection is not driving life to any particular end or goal, although it is capable of producing intelligent beings such as ourselves who can worry about this.

Case study: the avoidance of incest

One of the best and clearest illustrations of the difference between proximate and functional (ultimate) explanations arises from the Westermarck effect, a mechanism that offers an explanation for the avoidance of incest. In virtually all societies incest is frowned upon or declared illegal. Very few men have sex with their sisters or mothers. Sexual abuse of daughters by fathers is more common but still relatively rare compared to heterosexual sex between unrelated individuals. We can consider two explanations of these facts. One is that related individuals secretly desire incest but that culture imposes strict taboos to prevent its occurrence. The other is that humans possess some inherited mechanism that causes them not to find close relatives sexually attractive.

The first of these explanations came from Sigmund Freud. Freud’s theory suggested that people have inherent incestuous desires; they are not observed in action very often partly because they are ‘repressed’ and partly because society has (presumably for the benefit of the health of its members) imposed strict taboos. Suggesting that incestuous urges are repressed, and so difficult to observe, makes it difficult of course to refute the idea that we have them in the first place. A further difficulty is that Freud is essentially suggesting that evolution has not only failed to generate...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Routledge Modular Psychology

- Also available in this series (titles listed by syllabus section):

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Sexual reproduction

- 3: Sexual selection

- 4: Unravelling human sexuality

- 5: Archetypes of the psyche: Fears and anxieties as adaptive responses

- 6: Evolutionary explanations of mental disorders

- 7: The evolution of brain size

- 8: The evolution of intelligence

- 9: Study aids

- Key research summaries

- Glossary

- Answers to progress exercises

- References