- 904 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Policing

About this book

This new edition of the Handbook of Policing updates and expands the highly successful first edition, and now includes a completely new chapter on policing and forensics. It provides a comprehensive, but highly readable overview of policing in the UK, and is an essential reference point, combining the expertise of leading academic experts on policing and policing practitioners themselves.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Policing by Tim Newburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction:

understanding policing

Image and reality

Social scientific literature is now dominated by discussions of globalisation, risk, new forms of modernity and cognate terms. Though varied in focus, what this literature shares is a concern with understanding what is perceived to be the very significant and rapid changes affecting our society and those around us. These changes – however described – permeate all aspects of public life, including policing. What is in little doubt is that we live in complex times. That the police play a central role in the maintenance of order is rarely questioned. Most opinion polls asking questions about security return the finding that the public appetite for ‘more bobbies on the beat’ remains undimmed. Yet, it is also the case that people are now much more sceptical about the abilities of the police than once would have been the case and are likely to be much more critical about their interactions with police officers. Writing in the inter-war years Charles Reith, in his ‘orthodox’ history of the police, suggested that, ‘What is astonishing ... is the patience and blindness displayed both by citizens and authority in England over a period of nearly a hundred years, during which they persistently rejected the proposed and obvious police remedy for their increasing fears and sufferings’ (1938: v, emphasis added). It is rarer now for policing to be viewed as an obvious remedy for the problems that confront us for, as Reiner (2000: 217) notes, ‘police and policing cannot deliver on the great expectations now placed on them in terms of crime control’. Nevertheless, there remains considerable residual faith in this particular state institution.

It is worth reminding ourselves that public constabularies, in the sense we now know them, are less than two centuries old. Though there has only been concentrated scholarly attention on policing for a small part of that period, the police and policing are now a staple of sociological, criminological and popular discourse. There was considerable resistance to the introduction of the new police in the nineteenth century and, indeed, it was not until the mid-twentieth century that anything like a broad degree of social legitimacy was achieved in the UK. By any standards, the public police service is now a formidable social institution. Its size and its cost, for example, have grown dramatically.

The political situation in which policing operates has also changed markedly. Up until the late 1970s there existed broad agreement between the main political parties on questions of ‘law and order’. The end of this bipartisan consensus led to an intense battle over criminal justice generally, and arguably policing most particularly. The Thatcher administration signalled its desire to be perceived to be supportive of the police service by implementing the Edmund Davies pay agreement soon after reaching office in 1979. This led to a very substantial increase in police expenditure – doubling from £1.6 billion in 1979 to £3.4 billion in 1984, though with only a six per cent increase in staff levels. Although the pattern has been far from smooth since, expenditure has continued to rise, reaching £7.7 billion by 2000 and anticipated to rise to almost £13 billion during 2007–8 (Hansard, written answers 14 January 2008). This represents very nearly one half of total government expenditure on the criminal justice system. A significant element of recent increases in expenditure have been devoted to attempts to increase police numbers. Whilst this has by no means always been the focus of increased expenditure historically – as the Edmund Davies increases illustrate – nevertheless, police numbers have themselves increased substantially in recent decades. There were in the region of 50,000 police officers in 1955. This had increased to approximately 80,000 by 1975 and 118,000 by 1995. Total police officer strength stood at almost 142,000 by March 2007.

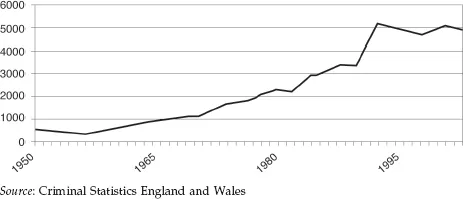

Such increased expenditure in part reflects the growing workload facing the police service. Whatever their other shortcomings, one thing that officially recorded crime rates are able to indicate fairly accurately is the number of calls on police time. Quite clearly this has expanded vastly in the post-war period. Notifiable offences recorded by the police, for example, grew from slightly over half a million in the early 1950s to substantially in excess of five million per annum at the beginning of the new century. The most dramatic increase occurred between 1980 and 1992, during which period recorded crime more than doubled.

There have been times when politicians assumed that increased expenditure on the police would lead, almost mechanically, to greater effectiveness in crime control (see, for example, Baker 1993). Whilst this is no longer the case, and indeed there is considerable scepticism in some quarters about police efficiency and effectiveness, there remains considerable competition between the political parties to be seen to be supportive of the police. Recent years have seen the police service become a much more effective lobbying body. ACPO, in particular, has become a key player in the politics of crime control and, in the main, Home Secretaries have been reluctant to take on the police service. One of the clearest ways in which political support can be delivered is through a commitment to provide increased resources and this has been a political stance that, for understandable reasons, the police service has been keen to encourage – and has generally managed to do successfully.

More problematic, however, has been the relationship between the police and the public. During the past 20 years there has been a substantial decline in public satisfaction with the police, with the proportion of people saying that the police do a ‘very good’ job declining from 43 per cent in 1982 to 24 per cent in 1992 and then again to 20 per cent in 2000 (see Figure 1.1), though overall levels of approval remain relatively high.

Figure 1.1 Recordedcrime, England and Wales, 1950–2000

In part, the continuing faith in the police relates to the important role that they have played, at least up until relatively recent times, as a focus for a particular conception of English identity and social order (Reiner 1991; Loader and Mulcahy 2003). More particularly, for the bulk of the post-war period the police have been able to call upon a large degree of support from significant sections of the population not because – or not entirely because – of what they do, but because of what they represent. The immediate post-war period, and the fictional figure of PC George Dixon, has come to take on a particular resonance in relation to British policing (see Reiner, this volume). Why this supposed ‘golden age’ has become such a powerful symbol is difficult precisely to fathom but, as Loader (1997: 16) suggests, it is likely not only to be ‘about the allure of a seemingly safer and more harmonious era; it is also a means of recalling just how great this medium-sized, multi-cultural, economically-declining, European nation once was’. Rising crime levels, together with a decline in faith in the efficacy of criminal justice generally, and the police in particular, together with a raft of socio-political changes to our way of life, have created significant challenges to this symbolic image of policing. Nevertheless, it remains the case that there is an almost endless public fascination with the police as an organisation and with policing as a set of activities.

Nowhere can this fascination be seen more clearly than in the changing media representations of policing in post-war Britain. As Reiner (this volume) and others note, important elements of the shifting nature of policing have been captured in the changing characters and representations in television drama, from the romantic and politically uncontroversial society policed by George Dixon, through the gradual emergence of an increasingly complex world of the 1960s and 1970s (Z-Cars and subsequently the regional crime squad in Softly, Softly), to the acknowledgement, and implicit acceptance, of police rule-breaking in the Flying Squad in The Sweeney. In some respects, the multiple representations now available on television – from hard-edged soap opera (The Bill)1 through attempts to recover a ‘golden age’ (Heartbeat) to farce (Thin Blue Line) and fly on the wall (Rail Cops, etc.) all the way to historical comparison (Life on Mars) – reflect the somewhat fractured and plural nature of contemporary policing, but also the somewhat more problematic relationship between policing and English/British national identity.

In part, such dramatic representations have much to tell us about the realities of policing, though they are also a potent source, reproduction and reinforcement of the myth and mystique that surrounds policing. As I have already implied, in recent times the police have become much more adept at managing and manipulating images and messages about what they are and what they do. Attempting to understand the changing nature of police representation, and how this relates to the realities of policing ‘on the ground’, is a central aim of this book. So plentiful, and sometimes so seductive, are the images of policing now available, that it is relatively easy to persuade ourselves that we understand and somehow ‘know’ policing. The Handbook focuses on the realities of contemporary policing, exploring the nature and organisation of policing activities, how policing is conducted, the problems and controversies that exist, and the key issues and debates that are likely to shape its possible futures.

Studying policing

In recent decades social scientists and historians have become increasingly preoccupied with policing. The socio-political changes of the 1960s permissive era set in train a number of changes in policing, as well as stimulating considerable academic thought on how policing should be theorised and understood. Since that period there has been a very significant expansion in both the sociology of the police and sociology for the police (Banton 1964). In recent times, in part reflecting the apparently increasingly complex policing division of labour, the sociology of policing has also grown substantially (Jones and Newburn 1998). At the same time ‘law and order’ in general, and policing in particular, have also become much more politicised and contested.

Much early work on policing focused on the nature of the police role and of police ‘culture’. In particular, work by Banton in the 1960s, Cain in the 1970s and Smith and Gray in the 1980s set the parameters for much that has followed. Banton's observation that the police officer is primarily a ‘peace officer’ rather than a ‘law officer’ spending relatively little time enforcing the law compared with ‘keeping the peace’ had a profound influence on subsequent criminological work in this area. Subsequent work also focused on what were primarily functional definitions of police work with Cain (1979), for example, arguing that the police ought to be defined in terms of their key practice – the maintenance of order. Despite criticism, much academic writing continued in this tradition of analysing what policing is in terms of what constabularies do, and much such work focused on the idea that a considerable portion of police work should be understood in terms other than crime control, or even order maintenance (Punch 1979). In contrast to studies focusing on the ‘police function’, work by Bittner and others focused on the legal capacity brought by the police to their activities. Starting from the position that neither the public generally, nor the police in particular, succeed particularly well in describing and justifying what it is that the police do, Bittner argued that it is the police's position as the sole agency with access to the state's monopoly of the legitimate use of force which makes them distinctive and accounts for the breadth of their role. As he put it:

the police are empowered and required to impose or, as the case may be, coerce a provisional solution upon emergent problems without having to brook or defer to opposition of any kind, and that further, their competence to intervene extends to every kind of emergency, without any exceptions whatever. This and this alone is what the existence of the police uniquely provides, and it is on this basis that they may be required to do the work of thief-catchers and of nurses, depending on the occasion (1974: 17).

Bittner's crucial contribution was to identify what was distinctive about the role and contribution of public constabularies.

As I suggested above, much of the early sociology of policing tended not to allow its gaze to stray much beyond the public police. Recent years have seen much greater attention paid to the private security sector and to the range of policing providers that lie somewhere between the ‘public’ and ‘private’ spheres (see Shearing and Stenning 1987; South 1988; Johnston 1992; Jones and Newburn 1998; Johnston and Shearing 2003), though the bulk of criminological attention continues to be paid to public constabularies – and this is the case for this volume too. The title of this volume – The Handbook of Policing – is deliberately chosen. Though much space is devoted to the nature and work of the police, wherever relevant authors have focused attention on other policing bodies. As such, it is very much a child of its time, taking the increasingly complex, fragmented and plural nature of policing as a major focus.

Two other major additions transformed the study of policing during this period. The first was the emergence of a set of critical historians who, in Reiner's (2000) terms, challenged the ‘cop-sided view of history’ with a revisionist ‘lop-sided’ account (e.g. Storch 1975). The result is a much richer history of policing arrangements, and one that is able to grasp the extraordinary story of increasing police legitimacy during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries whilst allowing for the fact that the power of the police is always contested (see, in particular, Reiner 2000, ch. 1). The second development was the emergence of a form of policy-oriented (administrative) criminology focusing in the main on police activity, operations and performance. Much of this was funded by government and was influenced by the dominant research paradigm emerging in the Home Office in particular in the late 1970s and 1980s (see e.g., Heal et al. 1985).

Work on the police has continued to expand since that time. Indeed, from a period 30 years ago in which the police service was, perhaps understandably, somewhat nervous about, and on occasion actively resistant to, criminological research, we now find ourselves in a position where most forces have some form of internal research capability, and all forces actively encourage research. The sub-discipline of police studies is now well established within British criminology and beyond. Both professionals within the police service itself and students studying criminology and related subjects are increasingly involved in the study of policing in its broad sense. Courses are proliferating and this shows no sign of diminishing. A number of specialist journals cater for, and facilitate, this market in ideas, and the range of books on policing – including book series – is increasing all the time. It is for this territory that the Handbook of Policing is designed.

The volume

This volume aims to provide a broad introduction to policing – attractive to students at all levels and to practitioners – without sacrificing its commitment to high quality scholarship. The intention in this volume has been to cover all the major aspects of policing – in its broad sense – inviting experts in their particular fields to address key themes in the history, theory and practice of policing. This is a range that is difficult to capture within a single book and, certainly, existing textbooks in this area have only attempted to cover part of this terrain. Thus, the Handbook of Policing has a broader focus than has hitherto been possible in a single volume on policing, and one of its aims, therefore, is to attempt to provide the core reading for an entire course on policing, supplemented by other boo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures, tables and boxes

- Table of statutes

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Introduction: understanding policing

- Part I Policing in Comparative and Historical Perspective

- Part II The Context of Policing

- Part III Doing Policing

- Part IV Themes and Debates in Policing

- Glossary

- Index