- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emotional Growth and Learning

About this book

When working with children, an understanding of the social interactions and relationships which influence emotional growth and learning is essential. Emotional Growth and Learning clarifies these processes and serves as a practical and theoretical resource for the training of teachers and other professionals. Paul Greenalgh draws on case studies from his own experience to illustrate the relevant concepts of Jungian, psychoanalytic and humanistic psychology . Individual and group exercises help adults to explore their own participation in the growth and learning processes and the book's multi-disciplinary approach and accessible style will appeal to teachers, parents and those working in clinical psychology, counselling and social work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Emotional Growth and Learning by Paul Greenhalgh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: EMOTIONAL GROWTH AND LEARNING— AND THEIR ENEMIES!

1 EMOTIONAL GROWTH AND LEARNING

INTRODUCTION

Bennathan (1992) makes the point that the importance of the overall ethos of a school for the progress of its pupils has been well recognised—for example in the classic Rutter et al.’s Fifteen Thousand Hours (1979)—but that teacher training has presented an over-simplified model of the child. This model is one which moves, with the help of a well-presented curriculum, through the Piagetian stages of cognitive development:

It is a model which lacks the understanding of the emotional causes of learning failure that have to do with the child’s early development, its home circumstances, its social experience, all factors which may have been so damaging that learning can hardly take place. This inadequacy was recognised by almost every enquiry into the good management of children in school from the Warnock Report in 1979 to the Elton Report in 1989. The call was always for more emphasis on understanding the emotional realities for many children. Children do not come to school with uniformly good experiences and attitudes. The good teacher knows this and both understands the subject to be taught and the nature of the child who is to be taught. It would be a most retrograde step to encourage teachers to think that understanding the curriculum is more important than understanding the child.

(Bennathan 1992:41)

Effective learning is dependent upon emotional growth. If we are to facilitate better the learning of those whose learning and emotional growth has become stuck, i.e. those children with emotional and behavioural difficulties, then we need to understand better the relationship between affect and learning. This calls first for a theoretical consideration. We will then look at those experiences which are necessary for emotional growth and learning to proceed.

AFFECT AND LEARNING

This discussion begins from a theoretical perspective, and then considers the stance taken by recent major reports upon work with affect and learning.

Affect is defined by Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary as ‘the emotion that lies behind action’. Affect is not static, neither is the capacity for learning, nor is a special educational need. So the way in which adults engage in affective processes has an impact on the child’s capacity for learning. Estrada et al. (1987) conclude, in their study of children at 4, 5, 6 and 12 years of age, that ‘the affective relationship (i.e. mother/child) continues to make a unique contribution to cognitive functioning beyond its influence in the early years’ (in Barrett and Trevitt 1991:10).

At a very general level, Capra (1982:324) argues that ‘human evolution …progresses through an interplay of inner and outer worlds, individuals and societies, nature and culture’. Capra’s comment applies equally to individual and collective processes of ‘evolution’. Something of the nature of this evolution is explained by ‘personal construct’ theory, developed by Kelly (1955). From the point of view of this theory, each of us is said to construct our own reality, coming to know the world only through personal interpretations, or the constructions that we make of it. Writing from the point of view of personal construct theory, Salmon explains that:

as members of a society, each of us has to achieve a workable understanding of our social world. It is the psychology we construct which allows us to define ourselves in relation to others, which underlies our moment-to-moment dealings, our social transactions, and governs the stances we take up, the projects we launch in the course of our lives.

(Salmon 1988:92)

Salmon argues that our ‘personal constucts’ develop when:

from the very beginning of life, interpretations—the meanings to be accorded to things—are offered and exchanged between infants and their care-givers…. A personal system of meaning has to be forged which is viable, liveable, yet which remains open rather than closed. Education, in this psychology, is the systematic interface between personal construct systems. This view of formal learning puts as much emphasis on teachers’ personal meanings as on those of learners…. Our personal construct systems carry what, in the broadest possible sense, each of us knows…. They represent the possibilities of action, the choices we can make. They embody the dimensions of meaning which give form to our experience, the kind of interpretation which we cast upon events. Since none of us can know anything of the world, except through the meanings we have available to us, the dimensions we have constructed—our constructs—are crucially important.

(Salmon 1988:22–3)

This has implications for the way we conceive of learning and of the function of the curriculum. Salmon argues that in the traditional mode of education, which assumes the transmission of ready-made understanding, validational outcomes are implicitly defined in terms of right and wrong. If knowledge is absolute, pupils either possess it or they do not. In a model based on personal constructs, validation has a different character, since knowledge, in whatever sphere, is never final.

What essentially matters is its viability in practical, personal and social terms. No formulation has sole rights. There are always many possible ways of defining things. Helpful validation then becomes, not a matter of final arbitration, but of simultaneously affirming and challenging existing constructions of meaning…. Whereas the traditional transmission model can insist on a single formulation of understanding, within a constructivist view, many viewpoints are possible.

(Salmon 1988:79, 83)

This formulation is important, given that each of us constructs our own meanings based on individual experience, since it allows for the possibility that, ultimately, children need to construct their understanding of the curriculum out of their own real experience. From this perspective, understanding does not proceed quantitatively, by a series of additive steps, but ‘by significant changes of position, of angle of approach, changes in the whole perspective from which things are viewed. It is, as Kelly saw it, a matter of imaginative reconstruction’ (Salmon 1988:72). This formulation parallels Dewey’s conception of education as the reconstruction of experience (Rogers 1961).

As Marris argues (1986), we grow up as adaptable beings, able to handle a wide variety of circumstances, only because our sense of meaning of life becomes more consolidated. Marris suggests that meanings are learned in the context of specific relationships and circumstances and we may not readily see how to translate them to an apparently different context.

Both learning theories and theories of personality focus attention on self-development as a process, which can be blocked or distorted, or assisted, but not replaced…[a person] construes his experience and therefore helps to determine what his experience shall be and what he will learn from it.

(Blackham 1978:30–1)

Piaget developed the notion that in order for a child to understand something, s/he must construct it for himself, must reinvent it. The evolution of each individual’s learning is dependent upon the capacity to symbolise— the basis of understanding language and number—and upon the development of sufficient autonomy to take the exploratory, inventive risks necessary for one’s own thinking. The level of functioning of the capacities for symbolisation and autonomy is related to emotional development. Piaget conceives intellectual development as evolving by the interplay of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation depends on an internal organising structure sufficiently developed, both cognitively and emotionally, to incorporate experience. Dockar-Drysdale (1990) distinguishes between the realisation, symbolisation and conceptualisation of experience, referring respectively to the capacities to experience inside oneself, to store the good inside oneself, and to use words to understand experience. ‘Experience must be realized and symbolized before it can be conceptualized’ (Dockar-Drysdale 1990:162).

Learning is a process of continual reordering of perceptions and knowledge in order to refine the sense one makes of one’s experiences. The qualities which we experience in others, and which we ‘take in’, consciously and unconsciously, have a significant impact upon our capacities as learners. A person’s inner capacities develop through a process of largely unconscious exploration of her/his relationship with the external world, as represented by significant other people. Theorists of the psychodynamic school have made the major contributions to our understanding of the emotional aspects of the processes involved in the construction of our experience. The notion of ‘object relations’ has made a significant contribution to psychodynamic thinking. Object relations theories are useful here since they help our understanding of the way in which we relate to parts of—or ‘objects’ in— our internal world, and the impact of these objects upon our experience of others. Individuals may unconsciously push out or ‘project’ parts of themselves onto other people, and experience this unwanted aspect of themselves in the other person. The projecting person may become identified with the person upon whom s/he is projecting, or the subject may identify him/herself with the projected material—the process known as ‘projective identification’. In this process the ‘content’ attributed with the other person (external object) may be reintrojected, or taken back inside by the projecting person. Whilst this mechanism may be used defensively (see Chapter Two), it is also important for growth. Responses related to such contents are the foundations for the capacity for empathy and become the prototype for more advanced forms of empathy. Empathy is an important basis for relationship, and it is through relationship that our sense of meanings develop.

The processes of projection and introjection take place unconsciously in early childhood. Through them we establish our subjective meanings and develop our sense of identity, increasingly learning to differentiate between what is ‘me’ and what is ‘not me’ (see the section below on ‘Emotional needs and learning’). A sense of security in one’s own identity is required to face the possibility of the unknown, the yet-to-be-invented. Without some security in our identity, we may experience such a task as a threat to our very sense of ourselves. This is particularly the case when we are vulnerable and without much ego strength, i.e. capacity to manage our feelings and to mediate between our inner and outer worlds. When we feel vulnerable, we are more likely to lose our capacity for imagination, the basis of the process of invention, so necessary for learning. In such situations it is as if the person has become—at least temporarily—frozen, emotionally stuck, as if unavailable for learning.

Given that the individual construction of meaning is so vital to the capacity for learning, it is not surprising that humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers, who also views the personality as a ‘process of becoming’ (1951), makes the following statements about teaching and learning. First, we cannot teach another person directly, we can but facilitate his/her learning. Second, significant learning takes place only of those things which the person perceives as being involved in the maintenance of, or enhancement of, the structure of the self. Third, significant learning is resisted, since the personality protects itself. If the person sees that the learning is going to require a reorganisation of self, s/he will not open up the boundaries of the personality to include new behaviours until the person feels that it is safe to do so and that the new behaviours are in his/her self-interest. Fourth, Rogers views the situation which most effectively promotes effective learning as one in which any threat to the self of the learner is reduced to a minimum, and in which learning is facilitated.

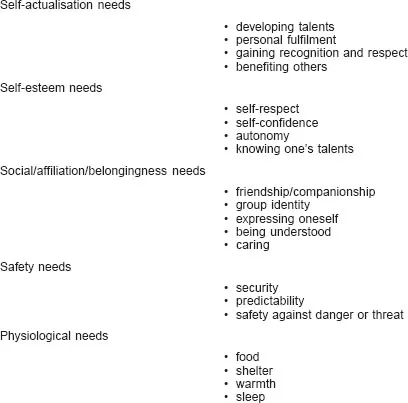

It is interesting to compare the developmental issues involved in a child’s construction of his/her experience with Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs (see Figure 2). Maslow suggests that only when one’s needs have been met at a particular point on the hierarchy is one able to ‘progress’ to fulfilling one’s needs at a higher level in the hierarchy. People achieve their potential when they are able to fulfil the characteristics shown at the top of his hierarchy.

Yet many children who experience emotional difficulties are struggling to establish their sense of basic safety, and to manage the anxiety which ensues from a lack of safety. Similarly, Erikson’s (1977) notion of developmental tasks begins with the concept of needing to resolve the conflict of basic trust versus mistrust. Children need to develop a sense of emotional safety and trust in others for development and learning to proceed. If we do not sufficiently establish personal constructs which provide nourishing forms of meaning and identity, then we will find little meaning in learning, and we will resist it. If part of the teachers’ role is to enhance access to learning for those who find it difficult, then this role also demands work to be undertaken on developing creatively meaningful personal constructs and identities. How do schools, our institutions responsible for fostering learning, relate to such tasks, and, more precisely, what sorts of encouragement have recent major reports given in this regard?

Figure 2 Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs

(adapted from Maslow 1943, 1954)

(adapted from Maslow 1943, 1954)

Traditionally schools have perceived themselves to have a legitimate and necessary concern to foster ‘personal’, or social and emotional, development. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate’s recent interpretation of the National Curriculum takes this into account when making the point that the Education Reform Act ‘includes the requirement that every pupil of school age has access to a balanced and broadly based curriculum, promoting personal development, and preparing that pupil for adult life’ (DES 1990:29). Hall and Hall (1988) state that there is convincing evidence to show that improving the quality of human relations in an institution also improves the quality and amount of academic work produced and the attendance of the students.

Where learning is impeded by distress or intense feelings, the child’s relationships with teachers, peers and family are often tense. It is particularly noteworthy that the National Curriculum Council (1989a:35) recognises these implications for the teacher’s role: ‘For pupils with emotional/ behavioural difficulties, there are dangers in over-emphasis on “managing” the behaviour without attempts to understand the child’s feelings.’ The teachers’ attitudes towards, and skills in, interactive processes go a considerable way to either meeting, or negatively reinforcing, the special educational needs. Yet the social and interactive skills required of pupils by the National Curriculum are, from an early age, demanding. For example, to take the risks necessary to formulate and test hypotheses, and to operate as a member of a group comparing results with other groups (as demanded in the early stages of the science syllabus), demands a considerable degree of autonomy. The teacher is asked not only to be sophisticated in interactive skills, but to facilitate the development of such skills in pupils struggling in this area themselves. The importance of the teacher’s role in this regard has been recognised and acknowledged by the Elton Report, Discipline in Schools:

We are convinced that there are skills, which all teachers need, involved in listening to young people and encouraging them to talk about their hopes and concerns before coming to a judgement about their behaviour. We consider that these basic counselling skills are particularly valuable for creating a supportive school atmosphere. The skills needed to work effectively with adults, whether teachers or parents, are equally crucial....

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT

- FIGURES

- EXERCISES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: EMOTIONAL GROWTH AND LEARNING— AND THEIR ENEMIES!

- PART II: FACILITATING EMOTIONAL GROWTH AND LEARNING

- AFTERWORD

- APPENDIX 1: THE TUTORIAL CLASS SERVICE

- APPENDIX 2: SANDPLAY

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY