eBook - ePub

Teaching Young Children to Draw

Imaginative Approaches to Representational Drawing

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Young Children to Draw

Imaginative Approaches to Representational Drawing

About this book

Now that art is a National Curriculum subject, teachers are looking for useful approaches to the teaching of art. This book offers an approach that has been developed by the three authors and has been shown, through research in schools, to improve

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Teaching Young Children to Draw by Mr Grant B Cooke,Grant Cooke,Dr Maureen V Cox,Maureen Cox,Deirdre Griffin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralWhy Teach Children to Draw?

1

· Why Teach Children to Draw?

Children operate as ‘artists’ from a very early age using different materials for personal expression and as a way of exploring and making sense of the world in which they are growing up. This process of development needs to be supported by parents and teachers in a variety of different ways, ranging from encouraging free and imaginative expression to exploring the work of other artists and putting children in touch with conventions which will enable them to develop their confidence and skills in visual thinking, problem solving and drawing as a means of communication. For, as Norman Freeman (1980) emphasizes, ‘children are not simply creatures expressing their essence through drawing, they are also novices who are learning how to draw’. This book is designed to provide teachers with an easily accessible and enjoyable approach to supporting children in their engagement with the drawing process.

Drawing as a way of making marks and controlling space on a flat surface is fundamental to all visual communication, whether for practical or artistic purposes. It can be the foundation for more imaginative picture making in art education, and has further importance as a medium in which children can record their observations in other areas of the curriculum and through which they can come to understand relationships and concepts important in a number of different subjects. A major problem for the teacher, and especially the non-specialist teacher, is how to go about the teaching of drawing. Since the subject has not attracted the same attention as some other aspects of the curriculum—such as reading, writing and number work—many teachers will have little or no training in how to teach drawing. Although most teachers provide opportunities for children to draw —as an art activity or as part of other project work—they have not necessarily considered the activity in its own right and how it might best be taught. It’s not surprising then that many teachers feel at a loss and that over 60 per cent, according to a recent survey (Clement, 1994), feel the need for further inservice training if they are to teach the art curriculum. The lessons

outlined in the main section of this book were originally devised as part of a professional development programme designed to introduce teachers working with infants to non-threatening ways of approaching the teaching of drawing.

Call for better provision and advice for art education in the UK was made in the early 1980s by, among others, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (1982) and HM Inspectorate (DES, 1983). Even in 1990, however, HM Inspectorate was still lamenting the lack of any coherent and informed practice in primary schools. Introduction of the National Curriculum led to the teaching of art being taken more seriously. The National Curriculum Art Working Group was set up to identify and advise on the objectives of the teaching of art as a foundation subject for pupils between the ages of 5 to 14 years. Their report (DES, 1991) identified drawing as an activity central to all work in art and design and highlighted the importance of drawing from observation. Subsequently the National Curriculum for Art in England (DFE, 1995) has included a number of statements concerning the need for recording observations and an emphasis on drawing. For example, at Key Stage 1 (age 5–7 years) pupils should be taught to ‘record what has been experienced, observed and imagined’ and ‘experiment with tools and techniques for drawing, etc.’ (p.3). At Key Stage 2 (age 7–11 years) they should be taught to ‘develop skills for recording from direct experience and imagination, and select and record from first-hand observation’, ‘record observations and ideas, and collect visual evidence and information, using a sketchbook’ and ‘experiment with and develop control of tools and techniques for drawing, etc.’ (p.4).

Drawing can be used in many different ways, and drawing from an observed model is just one strand of art education. However, it is important because it introduces children to a convention of representational image making which involves careful looking, critical thinking and decision making in relation to drawing. It is a form of visual communication which is relatively easy to ‘read’, and has been used and understood by many different cultures at different times throughout history.

Representational Drawing

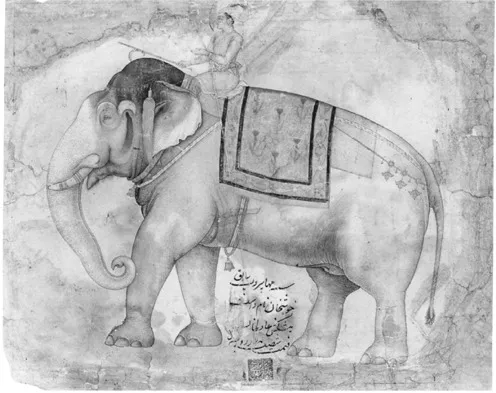

Representational modes of image making are often seen as essentially a Western art convention, associated with high points of achievement like the Renaissance, when clear visualization of three dimensional space became possible through the development of perspective. However, representational image making is also an important convention in World Art. Think of the correspondence with reality that one finds in Mogul miniatures and traditional Japanese prints, or in minor figures in ancient Egyptian wall paintings. There is a similar correspondence with reality in the huge hand-painted cinema hoardings in present day Madras and images in advertising which cross cultural boundaries. In these examples the artists have used different drawing techniques or ‘depth clues’ to suggest the spatial relationships between people and objects. They vary from what theorists would call ‘single point of view perspective’ and ‘foreshortening’ to flatter and more decorative indications of space using overlapping planes or ‘parallel oblique perspective’. But what they have in common is a recognizable connection between what we see in the picture and what we know from looking at the world around us.

In this Mogul miniature (figure 1.1)we can see elements of portraiture—the depiction of a particular, individual elephant. From this drawing we know the general shape of the animal and, because of the relative proportions of the mahout on its back, have some idea of its size. The sensitive rendition of the surface gives us some knowledge of the folds and textures of the elephant’s skin. We also gain fairly detailed information about the ceremonial trappings worn by the animal through the decorative detail of the cloth on its back, and the ornate harness with its tassels and bells which holds the regalia in place. We know and recognize these things because there is a correspondence between the drawn image and observed reality.

The Japanese print of three women picking mulberry leaves to feed silkworms (figure 1.2) has a flatter more decorative quality than we would find in European art of the same period. The artist has used parallel oblique perspective which, unlike the Western form of

perspective developed in the Renaissance, does not have receding lines converging on a single vanishing point. However, we have little difficulty in deciphering much of what is happening in this frozen moment of communication between the two women who are reaching up and grasping branches of the mulberry tree and the woman passing below with two full baskets of leaves balanced across her right shoulder. As well as being aesthetically satisfying, the image conveys a great deal of recognizable information, even when viewed from the perspective of a different time and culture.

The contemporary artists from the South of India who produced this hand-painted advertisement (figure 1.3) are using representational imagery in a similar way to convey key aspects of the film’s narrative—a dancer who continues her career despite having her leg amputated.

Of course there are vast differences between all these examples, and great differences in the traditions and types of training that lie behind the work. Over the centuries there has always been a degree of cross fertilization between different cultures, and the Mogul artist who drew the Imperial Elephant may well have been influenced by European artefacts in the same way that Western painters were at a later date influenced by the work of Japanese print makers. The hoarding painters in Madras are open to not only Indian and Western traditions of painting, but the influences of Indian and Western cinema, photography, and all that has become available world wide through new technologies.

1.1 ‘An Imperial Elephant’, tinted Mogul drawing on paper, circa 1640: © Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Many important culturally based meanings will only be truly accessible to the particular audience for whom the artwork was produced. However, the artists responsible for these representational images have used and developed schema in which there is some visual correspondence between the shapes created and observed aspects of reality. This is primarily a process of matching linear shapes with outlines of people or objects and is a form of representation which makes some obvious meanings readily accessible to viewers across time and cultures.

Cultural Influences

All our ideas are to a large extent shaped by the culture in which we grow up, and none of us develops in a cultural vacuum. We are all immersed in and influenced by the kinds of images we see around us —on film and television, in the street and in shops and galleries, in books and magazines. Even if we are not explicitly taught how to produce a particular image, what we do produce may still be influenced by the images we have been exposed to. When we study children in different cultures we can see that even though there may be individual variation in the images they create there is also a strong influence of the particular culture they are developing in (Wilson, 1985).

In some traditional cultures, in which adults produce formal designs but no representational artwork, the children may likewise create patterns but no representational pictorial forms (Fortes 1940, 1981; Alland, 1983). In other cultures where adult art is representational, the style of images produced by adults will influence the way that children draw. For example, a study in Bali (Belo, 1955) showed that when drawing the human figure the children adopted the style of the figures in shadow puppet plays popular in that culture. In Australia, young Warlpiri children listen to adults’ stories and see the accompanying illustrations they draw in the sand. When the children themselves draw, they reproduce the curved horse-shoe shape that adults use to denote a human figure; when they go to the community’s nursery school, they begin to draw typically ‘westernized’ versions of the human figure (Cox, 1993; Cox and Hill, 1996). In both styles of drawing the children make developmental changes—moving from simplified to more complex versions—and they will use both styles in the same picture (see figure 1.4 ). British children, growing up in today’s post-modernist world, can contextualize their own art work within a broad range of images from other cultures, constantly being expanded by advances in technology. They have access to many conventions and are soon able to ‘pick and mix’ in a way that was not open to previous generations. This provides teachers and children alike with opportunities to enjoy what Salman Rushdie (1990) refers to as rejoicing in our ‘mongrelization’, for ‘Melange, hotch-potch, a bit of this and a bit of that is how newness enters the world’.

1.2 ‘Sericulture’, Japanese print by Utamaro, circa 1798: © Copyright The British Museum, London

Very early on children recognize representational images as an important cultural convention. Before they have developed the ability to read written text, they are familiar with book illustrations, comics and advertising, and develop a sophisticated ability to ‘read’ and extrapolate from not only whole pictures, but parts of an image, guessing what the rest of the drawing might be. They realize the power of these conventions and the advantages of having control over them themselves. (For a fuller account of the development of children’s drawings, see Cox, 1992.)

Learning Through and About Drawing

Although sometimes dismissed as mere ‘scribbling’ the drawings of young children are purposeful and encapsulate important learning. In many ways these are the equivalent of children’s ‘role-play’, and might be said to have the same relationship to formal art work that make-believe play has to drama. Harnessing the child’s ability to experiment with different roles in drama involves teacher interventions within a facilitating structure, with a gradual referencing of the cultural conventions that underpin drama as an art form. We would suggest that the equivalent is true in terms of children’s mark making, with the teacher gradually introducing children to ways of thinking and organizing their drawing which allow them to assume more responsibility for their own development. What we therefore need to consider is the kind of teacher interventions that will support young children into new understandings about the drawing process and enable them to make their own informed decisions as they develop as artists.

Although we can argue about what it means to ‘teach’, to ‘educate’, to ‘learn’, and so on, most of us accept that we should do more than simply provide children with the materials and an interesting topic for their artwork. The transmission of knowledge and skill between people of the same generation and from one generation to the next allows for the possibility of rapid learning; without this cultural transmission, each generation would be condemned to re-create the wheel. One psychologist who set considerable store by the importance of cultural transmission was Lev Vygotsky (1934/1962). He argued that as early humans developed more technologically sophisticated tools to cope with the physical environment they also developed ways

1.3 Contemporary hand-painted cinema advertisement, Madras

of cooperating and communicating. Examples of these ‘psychological tools’ are speech, writing, systems of number and picture making. Vygotsky believed that children come to grips with these systems within a social context before they begin to use them independently for themselves. Although they may pick up some things by simple observation as well as through their own experience there is much which can be achieved by tuition.

When a child is confronted with a task or a problem there are many aspects to it and many potential routes to a solution; the child may not know that many of these are irrelevant or not viable. Without necessarily telling the child the answer an ‘expert’ adult can guide the child towards a potential solution. Thus, the adult’s role is to help the child to structure the way she thinks about the problem and guide her towards a solution. In this way, the child’s own knowledge and skill develops rapidly since she may discover a more sophisticated solution than she would otherwise achieve on her own. Vygotsky used the term ‘zone of proximal development’ to refer to this difference between what the child can achieve on her own and what she can achieve with tuition from others.

Drawing is used by both professional adults and children in many different ways. It is used to explore and play with ideas, to find solutions to problems and to communicate information and ideas to others in simple forms like diagrams and within more complex conventions like architects’ drawings. Shapes are made for their own sake, with the artist taking delight in pattern, colour and texture and engaging with the more formalist qualities of the medium. Drawing is used to tell stories and to illustrate or enhance narrative. It can be used to encapsulate sound and movement, with the child taking physical pleasure in acting with the medium as a story is dramatized, or the comic strip artist depicting sound effects as the super hero or heroine vanquishes the foe.

In school, representationa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures and Tables

- 1: Why Teach Children to Draw?

- 2: Examples of Lessons Using Negotiated Drawing

- 3: Things to Remember

- 4: More Ideas for Lessons

- 5: Research Findings

- References