- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Douglass Bailey's volume fills the huge gap that existed for a comprehensive synthesis, in English, of the archaeology of the Balkans between 6, 500 and 2, 000 BC; much research on the prehistory of Eastern Europe was inaccessible to a western audience before now, because of linguistic barriers.

Bailey argues against traditional interpretations of the period, which focus on the origins of agriculture and animal breeding. He demonstrates that this was a period when monumental social and material changes occurred in the lives of the people in this region, with new technologies and ways of displaying identity.

Balkan Prehistory will be required reading for everyone studying the Neolithic, Copper and early Bronze Ages of Eastern Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Balkan Prehistory by Douglass W. Bailey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SETTING THE SCENE

the Balkans before 6500 BC

The main issues of this book begin in the next chapter with the discussion of the fundamental changes evident in the Balkans from 6500 BC. To fully appreciate their significance, however, it is important first to set the scene by examining the region before this date. In the present chapter, discussion focuses on the late Pleistocene and early Holocene and includes a brief introduction to the upper Palaeolithic which, as suggested below, runs from c. 50,000 BP. A complete discussion of the Balkans during this period requires a book of its own.1 Here, attention is restricted to a few key sites, the most important trends in climate, lithic acquisition networks and developments in human behaviour such as the spatial organization of activities within sites and early forms of expressive material culture. We turn first to the beginnings of the upper Palaeolithic and note differences between it and the core areas of the European Palaeolithic; then we examine the evidence for early symbolic expressions of individual and group identities.

THE EARLY BALKANS

There is good evidence for a human presence in the Balkans from the middle Palaeolithic onwards, although the number of sites is limited (Darlas 1995).2 As in other regions, the transition from activities and sites of Archaic Homo sapiens and Neanderthals marks a significant break, with important changes not only in human subspecies (the appearance of Anatomically Modern Humans) who possessed new cognitive abilities but also in the types of artefacts made and used, the range of activities carried out and the places in which activities were focused.3

Transition to the upper Palaeolithic

In the Balkans, the changes which mark the earliest appearance of modern humans, as documented at Bacho Kiro at 46,000 BP, were not as drastic as elsewhere in Europe. Sites with early upper Palaeolithic material suggest that the transition was gradual At two key Bulgarian caves, Bacho Kiro and Temnata Dupka, the evidence for a measured transition includes types and frequencies of diagnostic material culture and patterns of environmental, climatic and faunal continuity which, significantly, were dissimilar from contemporary events in the core areas of Europe in the late Pleistocene.

Containing a long sequence of both middle and upper Palaeolithic activity, the cave at Bacho Kiro is an important site for understanding the Palaeolithic of Bulgaria and the Balkans. The site is located in the Strazha ridge on the northern border of the Stara Planina and thus sits between the moderately continental climate of the Danubian lowlands to the north and the sub-Balkan mountains and the Thracian plains of Mediterranean climate to the south.4 The sequence at the cave runs through fourteen layers which range from Atypical Charentian (layer 14) through non-Levallois Mousterian (13), Levallois-Mousterian (13/12), Mousterian (12), Bachokirian (11), Aurignacian (6a/7), Tardi-gravettian (5 and 4) and Neolithic (2–1).

One of the most significant results from Bacho Kiro was the identification of a local industrial complex, the Bachokirian, which has been identified as transitional from middle to upper Palaeolithic (Kozlowski 1979; Kozlowski et al. 1982). Found in the earliest upper Palaeolithic layers at the cave (layers 11/I—IV, 9, 8, 6b/7 and 7), the Bachokirian is defined by a predominance in the proportion of retouched blades over other forms such as retouched flakes, end-scrapers and splintered pieces. Particular, diagnostically important tools, such as burins, and truncated and notched pieces, occur rarely in these early assemblages. Indeed, burins and carinated end-scrapers only appear in the later layers of the site’s upper Palaeolithic sequence (layers 6a, 6b and 7). An absolute date from the beginning of layer 11 places the sequence at 43,000 BP (Mook 1982). Kozlowski and Alls worth-Jones have noted similarities between the content and structure of the Bachokirian assemblage at the eponymous site and of that from the lower layer at Istàllösko in Hungary (Ginter and Kozlowski 1982; Allsworth-Jones 1986). Dates from the latter site of 44,000 BP confirm the contemporaneity. Svoboda and Simán (1989:288) have argued that the Bachokirian is best understood as a transitional phenomenon similar in significance, if not necessarily in material culture, to other transitional phenomena in other parts of Europe, such as the Szeletian and Bohunician.

Aurignacian assemblages, the definitive material of the early upper Palaeolithic, appear at Bacho Kiro in the phases after the Bachokirian, at Temnata Dupka and at several other early sites, such as Istállosko; the assemblages are similar to early Aurignacian material from the Near East such as that found at Boker Tachit area A (Allsworth-Jones 1986:197–8). The content of the early Aurignacian assemblages at Bacho Kiro reveals a gradual development of this phase; this is especially clear in the appearance of the small numbers of bone points and an increase in end-scrapers and retouched tools in layers 9, 8, 7/6b and 7. Typical Aurignacian elements, such as high end-scrapers, are not present. It is only in layers 6a and 7 that a typical Aurignacian assemblage appears at the site; the frequency of end-scrapers equals that of retouched blades, and bone points (with round cross-sections) appear more frequently as, for the first time, do carinated end-scrapers and burins.

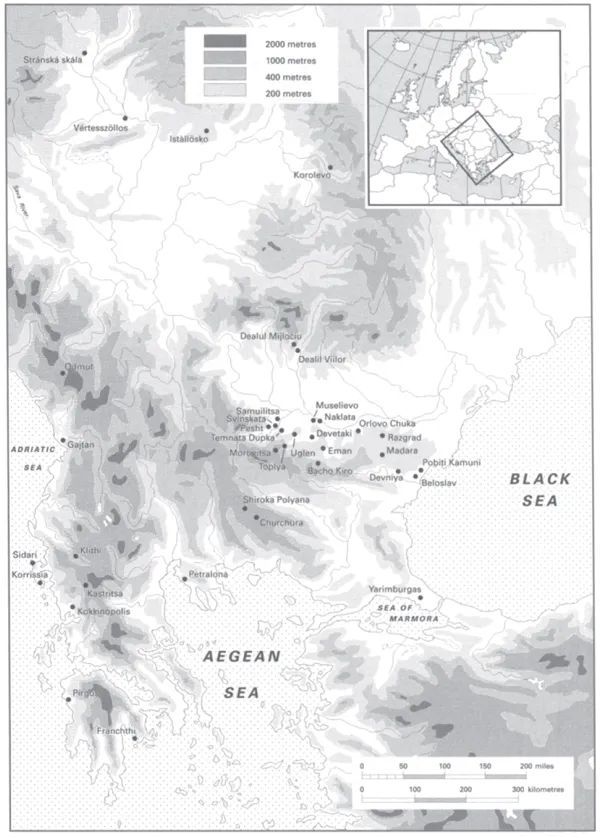

Figuer 1.1 Map of key sites discussed in Chapter 1

Climatic, floral and fauna components of the transition

In terms of at least some of the earliest upper Palaeolithic material, therefore, the transition to the upper Palaeolithic appears as a gradual shift and not a sharp replacement of entire sets of tools and technologies. Fundamental to the background of the transition were the contemporary climate, flora and fauna. This environmental background reinforces the suggestion that the late Pleistocene Balkans was distinct from regions to the north and west.

Three types of plant communities existed over central and eastern Europe in the run-up to the late glacial maximum at 18,000 BP: periglacial-tundra, periglacial-steppe and boreal forest. The first two of these existed in environments where permafrost was present. The third, boreal forests, was confined to enclaves in southern Europe, in the east Carpathians and in the Ukrainian upland (Starkell 1977:360). What is significant in a comparison of the Balkans with central, western and northern Europe is that during the pleniglacial, from 75,000 to 20000 BP, the southern extent of permafrost reached no farther than 48° latitude and even at 18,000 BP no further than 45°; thus even during the late glacial maximum the most southern extent of permafrost did not reach beyond the Danube.

During the last interglacial and full glacial, between 128,000 and 13,000 BP, therefore, the Balkans was not affected by the inland ice, permafrost, tundra or arctic desert or forest tundra that developed in areas to the north and west (Starkell 1977:363, figure 7). During the late interglacial and the first part of the early glacial (128–75,000 BP) the Balkan landscapes alternated through cycles of deciduous forest and forest-steppe. During the rest of the early glacial and most of the full glacial (from 75,000 to 13,000 BP), cycles of forest-steppe varied with those of steppe conditions (Starkell 1977: figure 7). The presence of forest-steppe and steppe also suggests that the Balkans was less dramatically affected by glaciation than were regions to the north and west.

The Balkans did not, however, avoid completely the effects of the climate changes which were having more monumental effects in other regions. Van Andel and Shackleton (1982) have argued that the sea-levels of the late glacial Aegean and Adriatic were 100 m below their modern levels. At 18,000 BP the northern Aegean and northern Adriatic seas were large coastal plains, rich enough in plants and animals to support mobile or semi-permanent groups of hunters, foragers, gatherers and fishers throughout the year (van Andel and Shackleton 1982:451). The post-glacial loss of these rich coastal plains and their resource abundances may have stimulated the shift in exploitation patterns noted by Geoff Bailey in the Epirus region (G.Bailey 1992; G.Bailey et al.1983a, 1983b). Here new upland areas came into use at this time, as seen at the Klithi rock shelter and the Kastritsa cave. Klithi was only used between 16,000 and 10,000 BP: before and after these periods human activity was confined to the Kónitsa plain.

The now submerged coastal shelf of the western Black Sea would have been a similarly productive resource zone. From 16,000 BP the European ice-sheets began their retreat in the face of warming conditions. Sea-levels in the Adriatic and Aegean rose to within 25–40 m of their current levels and covered much of the rich coastal plains (van Andel and Shackleton 1982). The same process occurred in the Black Sea, especially along the western and north-western coasts, where the modern shoreline lies 100–150 km from its position during late Pleistocene (Ryan et al. 1997a, 1997b).

Animals and refugia

While much of Europe was suffering the rapid expansion of ice-sheets as they reached their maximum southern extent and thickness at 18,000 BP, there were less drastic changes in the plant and animal populations of the Balkans and the Mediterranean. In its position as a palaeoecological transition between the Mediterranean and European biotopes, south-eastern Europe, during the coldest periods, was home to refuge populations of thermophilous taxa of plants and species of animals (G.Bailey 1992:8; 1995a: 519). In northern and western Europe, at this time, unglaciated areas were periglacial steppe and supported woolly mammoth, reindeer and horse. In the south-east a lowering of temperature and the related increase in aridity facilitated the spread of open steppe, a reduction of tree cover and the development of landscapes which supported grazing by herds of deer, cattle and steppe ass (G.Bailey 1992). Similar conditions undoubtedly dominated southern and eastern Bulgaria and perhaps northern Bulgaria and southern Romania.

Clive Gamble has identified red deer, horse, bos/bison and reindeer as the four principal species upon which Palaeolithic subsistence was based (Gamble 1986:101). These species were distinct. They appeared in large numbers and high densities, had body sizes large enough to return the investment of energy expended in their hunting and had reproductive rates rapid enough to support population survival despite losses to hunting. A second group of Pleistocene animals consisted of musk ox, elk, roe deer, ibex and chamois. These animals are distinct from the principal species either in their higher reproductive rates or by lower degrees of migration. Since many of these latter species could be precisely and predictably located in the landscape, they provided reliable alternatives and thus could have been exploited, when necessary, to make up for any failures in hunting the four riskier species of the principal group. The distinction is important as it can help to refine our understanding of hunting activities and site selection.

In their early phases, sites like Bacho Kiro probably served as temporary foci for hunting activities. They were points in flexible, impermanent networks of sites and micro-regions which stretched over large areas. People moved through these networks in search of resources ranging from high-quality materials for tool production, such as good quality flint, to predictably located animals, such as residential species like the ibex and chamois. In the middle Palaeolithic therefore, people came to the Bacho Kiro cave in order to exploit these predictable and residential species which occupied the mountainous micro-regions near the site. During some visits to the cave people capitalized on the less predictable appearances of the more mobile, more productive species such as red deer, aurochs, bison and horse that were at home in the forest and grasslands which also developed from time to time near the site.

Following Gamble’s summary of species behaviour during the Pleistocene (Gamble 1986:103–12), the middle Palaeolithic faunal evidence from Bacho Kiro suggests that use of the cave was conditioned by its position in an area in which migratory forest and grassland species such as red deer and horse could have been taken in combination with mountain species. Availability of the residentiary predictable and stable ibex and chamois communities would have provided a degree of security against the possibility of failure in the riskier hunting of the less predictable, more mobile, forest and grassland species of deer and horse. For the upper Palaeolithic at Bacho Kiro the site existed in a colder and drier climate than during the middle Palaeolithic (Madeyska 1982). The area around the cave became increasingly, though not completely, deforested and contained a more open landscape with steppe vegetation.

Through his analysis of the upper Palaeolithic fauna from Bacho Kiro, Kowalski has highlighted the differences between these Balkan conditions and those documented in the late glacial assemblages of western and central Europe (Kowalski 1982). The Bacho Kiro material lacks some species, such as lemmings, which are normally associated with tundra regimes. Bacho Kiro also has a higher proportion of steppe species, contains several steppe species which never reached the more northern regions and includes forest species which had disappeared in central Europe during the coldest phases (Kowalski 1982:67). Indeed, throughout almost the entire upper Palaeolithic sequence at Bacho Kiro, forest species were present. If analogies in terms of fauna are sought, they are best found in the material from contemporary caves to the east in Dobrudzha such as La Adam and Bursucilor and not to the west and north.

The micro-region around the Temnata Dupka cave, the other key Bulgarian site, was a refuge for animal species during the most drastic parts of the upper pleniglacial (Ginter et al. 1992:329). The presence of elk through the entire upper pleniglacial and the absence of species such as reindeer, which are characteristic for the European periglacial, supports this proposal The studies of the Temnata rodents and small mammals (V.V. Popov 1986, 1994) and pollen (Marambet 1992) confirm the differences which set the Balkans apart from central and western Europe. Thus, at Temnata, there is no evidence for any of the small mammal species which are characteristic of cold, periglacial conditions in other parts of Europe. Similar distinctions are noted with respect to larger mammals (Delpeche and Guadelli 1992) and birds (Z.Boev 1994). Popov suggests that the Balkans at this time was cooler, but not necessarily colder, than it is today and certainly experienced less extreme conditions than those faced in other regions during the later upper Palaeolithic. The most significant difference between present conditions at Temnata and those of the later upper Palaeolithic has more to do with humidity than temperature. Lower precipitation and lower temperatures would have favoured a domination of landscapes by open vegetation favouring species at home in forest-steppe, bush and dry meadow conditions.

Based on the detailed work undertaken at Temnata Dupka and Bacho Kiro, fundamental differences in environment are evident between east and west-central Europe during the upper Palaeolithic. If additional evidence is needed, a comparison of north Bulgarian conditions with those of Acquitaine in France illustrates the key differences between two otherwise topographically similar regions at the late glacial maximum. In comparison with the west, the annual mean temperature in Bulgaria would have been higher (12°C rather than ±7°C), as would have been the average January temperature (-2 to 0°C rather than -8 to 0°C) and the average July temperature (20–22°C rather than 12– 16°C). The annual mean precipitation would also have been greater in Bulgaria (550–600 mm rather than 450–500 mm) (Laville et al. 1994:324). Furthermore, although both regions are located on the southern extremes of large boreal plains, the one in northern Bulgaria did not support large arctic mammals such as reindeer or saiga antelope which are well known from the French context after 19,000 BP. Furthermore, the presence of elk at Temnata highlights its absence at contemporary sites in south-west and eastern France (Delpeche and Guadelli 1992:208).

To the detailed analyses of Bacho Kiro and Temnata can be added the evidence from Balkan pollen records. Kathy Willis has shown that the late-glacial climatic oscillations documented in north-western Europe pollen records are not present in the Balkans (Willis 1994:784). Willis studied the pollen records from ten palaeoecological sites in the Balkans containing deposits extending back to the last glacial period between 75,000 and 14,000 BP (Willis 1994). As one might expect, and as occurs in much of unglaciated northern Europe, her diagrams contained indicators for Artemesia-Chenopodiacae steppe, thus suggesting drier conditions for the full glacial. Unexpectedly however, the Balkan diagrams also document a continuous presence of coniferous and deciduous tree taxa which would not have been present in the northern regions (Willis 1994:772). Willis suggested that the evidence for low, but persistent, levels of pollen from temperate tree taxa originated from local refugial populations. Indeed, many temperate taxa appear to have survived in the Balkans throughout the last glacial (Willis 1994:769). A combination of altitudinal diversity (that is to say, large variations in precipitation and temperature due to changes in topography), little or no ice cover during the last glacial, and July temperatures only 5°C lower than at present suggest that the Balkans provided suitable micro-environments for the survival of temperate tree taxa during the last glacial period (Willis 1994:769). The vegetational history of the Balkans has not been subject to the immigration of additional taxa at any time from the last glacial to the present. Indeed, the fact that the diversity of present-day plant-life in the Balkans is richer than that of any comparable area in Europe may be due to survival from the Quaternary ice ages of a flora which contains many ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION: BALKAN PREHISTORY (6500–2000 BC)

- 1: SETTING THE SCENE

- 2: BUILDING SOCIAL ENVIRONMENTS (6500–5500 BC)

- 3: NEW DIMENSIONS OF MATERIAL CULTURE

- 4: CONTINUITY OR CHANGE?

- 5: CONTINUITIES, EXPANSION AND ACCELERATION OF BUILDING AND ECONOMY (5500–3600 BC)

- 6: BURIAL AND EXPRESSIVE MATERIAL CULTURE (5500–3600 BC)

- 7: TRANSITIONS TO NEW WAYS OF LIVING

- 8: THE BALKANS (6500–2500 BC)

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY