![]()

Part I

Principles

Building an Adaptive Model

![]()

1

Thermal Comfort

Why it is Important

Most people have a daily thermal routine. Within limits we expect to know how warm the bedroom will be when we awake, the kitchen when we have breakfast. We also know what to expect on the bus (or bicycle) journey to work and at the office when we arrive. These ‘expected’ environments can vary from time to time and from season to season, but on the whole we know what thermal conditions to expect over a day or month and we will generally have strategies for dealing with them – or rushing through those parts that are not acceptable. So why is it important to know which temperatures are comfortable? What is the purpose of the science of thermal comfort?

1.1 User Satisfaction

1.1.1 Comfort

In his survey of user satisfaction in buildings with passive solar features, Griffiths (1990) found that having the ‘right temperature’ was one of the things people considered most important about a building. This is a result that has been borne out by many other surveys over the years. Griffiths also found that ‘air freshness’ was an important requirement mentioned by the respondents to his survey. The subjective freshness of the air was found by Croome and Gan (1994) among others to be closely related to the temperature of the air. In other words, two important features in the user satisfaction with a building are closely related to temperature.

At the same time, dissatisfaction with the thermal environment is widespread, even in buildings with sophisticated controls. Complaints of overheating in winter and coldness in air-conditioned buildings in summertime are commonplace. A survey in an air-conditioned building carried out by students of Oxford Brookes University with the Building Research Establishment (BRE) found almost 30 per cent of occupants found the building too hot in winter.

1.1.2 Health

We are mammals and the human body must be kept at a constant internal temperature known as our ‘core temperature’. Much of the time this is done by physiological processes, by diverting the blood towards or away from the periphery of the body to control the heat loss from the skin, by producing sweat to cool the skin by evaporation, or by shivering when we are cold. In this context thermal discomfort is essentially a warning that the environment might present a danger to health. If we feel too cold we will take actions to make ourselves warm and comfortable again, or if too warm, to cool ourselves before the core temperature changes too much.

The threat of climate change and the increasing instances of hotter than normal conditions reinforces the pressing need (Nakicenovic and Swart, 2010; Figure 1.1 in Plates) to improve the buildings we occupy to protect ourselves from future climate conditions:

The spike … is the 2003 heatwave that killed about 35,000 people in France, Italy and Spain. The continuation of the heating trend under mid-range climate change scenarios would make the heatwave – which was about a one-in-a-100-year event at the time it occurred and a one-in-250-year event before humans started fiddling with climate – into a one-in-two-year event by 2050. In 2070, those deadly conditions of 2003 will be considered an unusually cool summer.

(Holdren, 2008)

Cold winters continue to result in excess winter deaths not least because an increasing number of people are falling into fuel poverty as the cost of gas and electricity soar and the global recession takes its toll. A person or family is said to be in fuel poverty in the UK if more than 10 per cent of their disposable income is required to ensure a comfortable temperature in their home. The number of people in fuel poverty is thus a function of the cost of fuel as well as the incidence of poverty in the population. Rising fuel poverty is characterised by the rise in deaths and heat- and cold-related illnesses become more common causing a rise in morbidity (illnesses) and mortality (deaths) during extreme weather events (Roaf et al., 2009). Even in many developed nations fuel poverty levels are very high. By the summer of 2011 around 35 per cent of all homes in Scotland were deemed to be in fuel poverty.

1.1.3 Delight

In her book Thermal Delight in Architecture, Lisa Heschong (1979) suggests that we can and should look for more than simply comfort in buildings, and consider that our thermal sense is capable of giving not just ‘satisfaction’ but in certain circumstances actually producing delight. This is especially true when we experience a variable environment. Following the work of Chatonnet and Cabanac (1965) and Cabanac (1992) on the ways in which our thermal sensations relate to comfort, Richard de Dear (2011) relates the delight we feel in the thermal environment in those aspects that tend to return the thermal state of the body to equilibrium. So the movement of the air around us, which tends to cool the body, is unpleasant when we are already feeling cold but can be delightful if we are warm.

1.2 Energy Consumption

The indoor temperature that is set for a building in the heating or cooling season is key to the energy used in the building. The heat loss from, or gain in, the building depends on the indoor– outdoor temperature difference. In the UK roughly 10 per cent of the heating energy used in winter is typically saved by a reduction of 1K in the indoor temperature.1 This saving includes contributions from the reduced indoor–outdoor temperature difference and a decrease in the length of the heating season. A lower indoor temperature means that the heating can be turned on later in the autumn, and can be turned off earlier in the spring. Because of a reduction in maximum heat load the buildings will also need a less powerful heating system.

Similar considerations apply to air-conditioned buildings: a decrease in the outdoor–indoor temperature difference will decrease the ‘cooling load’ – the energy needed to cool the building to a comfortable temperature. There are two factors that make the reduction of cooling loads for air conditioning an area of critical concern. First, air conditioning uses electrical power, which is highly inefficient in its generation if fossil fuels are used. It consequently wastes large amounts of energy to cool a building. Haves et al. (1992) have suggested that the energy used and wasted in the air conditioning of buildings is a significant driver for global warming and creates a positive feedback loop because higher temperatures result in more air conditioning use.

Second, the wide-scale use of air conditioning in countries such as the USA has led to ‘energy hog’ buildings and has discouraged buildings that use ‘passive’ – non mechanical – cooling strategies (Cooper, 1998; Ackerman, 2002). The need for air conditioning can often be significantly reduced or removed altogether by improving the thermal performance of the building through strategies such as reduced glazed areas, more shading, increasing levels of thermal mass, and naturally ventilating the building for as much of the year as possible.

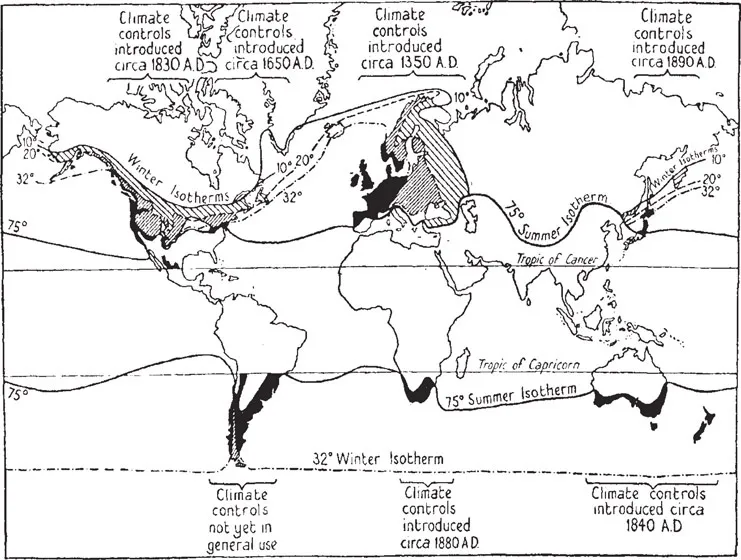

There is no question that in some parts of the world buildings require heating, and in others parts they need cooling to remain habitable (Figure 1.2). Our challenge is to minimise the period of the year over which these systems need to be used. The two key elements in the solution to this challenge are to design better buildings and to use an adaptive approach to achieving comfort in them.

Figure 1.2 A map of the world in 1939 by S.F. Markham showing those parts of the world in black that are most suitable for habitation by Homo Sapiens because they are the areas that require neither excessive heating nor cooling of buildings. Markham was clear that the miracle of air conditioning would open large parts of the world to exploitation by European white men who function best in cooler temperatures.

1.3 Standards, Guidelines and Legislation for Indoor Temperature

Both the comfort of the occupants of a building and the energy it consumes are closely linked to indoor temperature. The indoor temperature is clearly a prime concern for the owners of buildings and the people who live and work in them. The method by which we decide what temperature to aim for in a building therefore has far-reaching consequences.

One way in which we can decide what temperature to provide in a building is by reference to international temperature standards. Most temperature standards suggest a method for deciding an optimal temperature for a given space or building depending on its intended use, especially if the temperature is mechanically regulated by the heating or cooling system. ISO 7730 (2005) is an example of such a standard. The temperatures recommended result from calculations based on the activity of the occupants of a building and their clothing (more will be said about this approach in Chapter 4).

Guidelines for deciding on the best indoor temperature for different types of buildings or for different spaces within a building are available from such sources as CIBSE Guide A (2006) or the ASHRAE Guide and Databook (2009). It is to these sources that many heating and ventilating engineers will turn when deciding what temperatures to use in their calculations. These guidelines are based on professional experience and informed by comfort standards but reflect the assumption that for a given activity there is a given ‘best temperature’ and that this is correct for all circumstances. We know of no similar source for architects and this may be a reflection of the way they have handed responsibility for the indoor environment to engineers, to the detriment of the architectural profession and possibly of the buildings they design.

In most countries there is also legislation that sets limits on temperature, with the aim of protecting health and well-being, such as the UK Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act (1963) which sets a minimum temperature for working environments.

1.4 Adaptation

Experience tells us that an indoor temperature that varies with the weather is possible and often desirable in any building. Temperatures that are ‘right’ in summer when wearing a T-shirt and shorts could be oppressively hot in winter clothing. We expect different thermal experiences in summer and winter, and we modify our behaviour accordingly. The relationship between indoor comfort and outdoor temperatures in different climates can be used to suggest appropriate features for a low-energy design. This can be done by using the Nicol graph (Roaf et al., 2012) which relates preferred indoor comfort temperatures of adapted populations to outdoor temperatures at different times of year for a given climate (see Figure 6.4).

Recently international standards (e.g. ASHRAE 55-2004) and the European Standard EN15251 (CEN, 2007) have recognised the possibility that the comfort temperature can vary with changing outdoor conditions. These variable or adaptive standards are taken to apply in buildings that are naturally ventilated. A similar relationship could be assumed for heated or cooled (mechanically conditioned) buildings and certainly no validated reasons have been suggested why this should not be so. A variable standard requires comfort temperatures to change with the climate surrounding the building. It reduces the average indoor–outdoor temperature difference, and consequently reduces energy requirements considerably as against a single-temperature standard. Some authors suggest this could be...