- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women and Development in the Third World

About this book

For all societies, the common denominator of gender is female subordination. For women of the Third World the effects of this position are worsened by economic crisis, the legacy of colonialism, as well as patriarchal attitudes and economic crises.Feminist critique has introduced the gender factor to development theory, arguing that the equal distribution of the benefits of economic development can only be achieved through a radical restructuring of the process of development. This important new book reviews both policy and practice in Latin America, Africa and Asia and raises thought-provoking questions concerning the role of development planning and the empowerment of women.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women and Development in the Third World by Janet Momsen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The development process affects women and men differentially. The after effects of colonialism and the peripheral position of Third World countries in the world economy exacerbate the effects of sexual discrimination on women. The penetration of capitalism, leading to the modernization and restructuring of traditional economies, often increases the disadvantages suffered by women as the modern sector takes over many of the economic activities, such as food processing and making of clothes, which had long been the means by which women supported themselves and their families. A majority of the new and better-paid jobs go to men but male income is less likely to be spent on the family.

Modernization of agriculture has altered the division of labour between the sexes, increasing women’s dependent status as well as their workload. Women often lose control over resources such as land and are generally excluded from access to new technology. Male mobility is higher than female, both between places and between jobs, and more women are being left alone to support children. Women in the Third World now carry a double or even triple burden of work as they cope with housework, childcare and subsistence food production, in addition to an expanding involvement in paid employment. Everywhere women work longer hours than men. How women cope with declining status, heavier work burdens and growing impoverishment is crucial to the success of development policies in the Third World.

Women constitute almost half the world’s population but even today there are 80 million fewer girls than boys enrolled in school. Women carry the burden of two-thirds of the total hours of work performed. For this they earn a mere 10 per cent of the world’s income and own but 1 per cent of the property. Women produce more than half of the locally-grown food in developing countries and as much as 80 per cent in Africa.

Within these broad generalizations women’s lives in different places show great variation: most typists in Martinique are women but this is not so in Madras, just as women make up the vast majority of domestic servants in Lima but not in Lagos. Nearly 90 per cent of sales workers in Accra are women but this proportion falls to a bare 1 per cent in Algeria. In every country, the jobs done predominantly by women are the least well paid and have the lowest status. Clearly female and male roles are neither equal nor fixed. They differ from place to place and this spatial variation is most marked in the Third World. The relationship between these spatial patterns and development is the theme of this book.

Forty years ago, in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reaffirmed the belief in the equal rights of men and women, first laid down by the nations of the world in the Charter of the United Nations. Today it is clear that progress towards equality for women in most parts of the world is considerably less than that which was promised. However, disparities between women in different countries are greater than those between men and women in any one country. Life expectancy at birth for women varies from 74 years in Cuba to 43 in Chad. The proportion of illiterates in the female population varies from 99 per cent in Ethiopia to less than 1 per cent in Barbados. Even within individual countries women are not a homogeneous group but can be differentiated by class, ethnicity and life stage. Thus the range on most socio-economic measures is wider for women than for men and is greatest among the countries of the Third World.

We have now reached the end of the United Nations Third Development Decade while the Decade for Women culminated in a conference in Nairobi in 1985. At the conclusion of the first two Development Decades it was found that the extent of poverty, disease, illiteracy and unemployment in the Third World had increased. During the 1980s we have witnessed unprecedented growth of Third World debt and acute famine in Africa. Similarly the Decade for Women saw only very limited changes in patriarchal attitudes, that is institutionalized male dominance, and few areas where modernization was associated with a reversal of the overwhelming subordination of women.

Yet despite the apparent lack of change, the United Nations Decade for Women achieved a new awareness of the need to consider women when planning for development. In the United States the Percy Amendment of 1973 ensured that women had to be specifically included in all projects of the Agency for International Development. The British Commonwealth established a Woman and Development programme in 1980 supported by all member countries. In many parts of the Third World women’s organizations and networks at the community and national level have come to play an increasingly important role in the initiation and implementation of development projects. Above all, the Decade for Women brought about a realization that data collection and research were needed in order to document the situation of women throughout the world. The consequent outpouring of information has made this book possible.

Women and development

Prior to 1970 it was thought that the development process affected men and women in the same way. Productivity was equated with the cash economy and so most of women’s work was ignored. When it became apparent that economic development did not automatically eradicate poverty through trickle-down effects, the problems of distribution and equality of benefits to the various segments of the population became of major importance in development theory. Research on women in Third World countries challenged the most fundamental assumptions of international development, added a gender dimension to the study of the development process, and demanded a new theoretical approach.

The early 1970s’ model of ‘integration’, based on the belief that women could be brought into existing modes of benevolent development without a major restructuring of the process of development, has been the object of much feminist critique. The alternative vision, recently put forward, of development with women, demands not just a bigger piece of someone else’s pie, but a whole new dish, prepared, baked and distributed equally. International development has been challenged to transform itself into a process that is both human-centred and environmentally conservationist.

The principal themes

Three fundamental themes have emerged from the literature on women and development. The first is the realization that all societies have established a clear-cut division of labour by sex, although what is considered a male or female task varies cross-culturally, implying that there is no natural and fixed gender division of labour. Secondly, research has shown that in order to comprehend gender roles in production, we also need to understand gender roles within the household. The integration of women’s reproductive and productive work within the private sphere of the home and in the public sphere outside must be considered if we are to appreciate the dynamics of women’s role in development. The third fundamental finding is that economic development has been shown to have a differential impact on men and women and the impact on women has, with few exceptions, generally been negative. These three themes will be examined in the chapters that follow.

The overall framework of the book is provided by spatial patterns of gender. Gender is a social phenomenon, socially constructed, while sex is biologically determined. Gender may be derived, to a greater or lesser degree, from the interaction of material culture with the biological differences between the sexes. Since gender is created by society its meaning will vary from society to society and will change over time. Yet, for all societies, the common denominator of gender is female subordination, although relations of power between men and women may be experienced and expressed in quite different ways in different places and at different times. Spatial variations in the construction of gender are considered at several scales of analysis, from continental patterns, through national and regional variations, to the interplay of power between men and women at the household level.

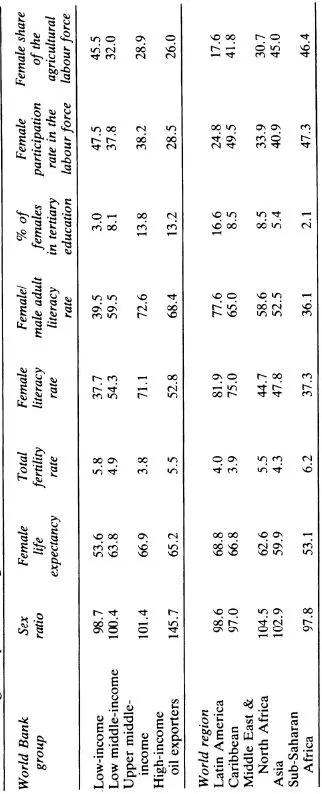

Table 1.1 provides a macro-scale view of women’s position on various indicators for countries grouped according both to income level and to location in the Third World. Low-income countries are characterized by populations in which women form a majority. These women bear many children and are poorly educated but undertake a high proportion of the work, especially in agriculture. In most cases, as national income increases, the sex ratio becomes more balanced and women have fewer children, are better educated and do less agricultural work. Yet the high-income, oil-exporting countries of the Middle East and North Africa have predominantly male populations because of the immigration of male workers, while the women have high fertility rates and low levels of economic activity despite relatively high participation in tertiary education.

Table 1.1 Regional patterns of gender differences

Sources: The World Bank, World Development Report, 1985 New York: Oxford University Press. R. L. Sivard, (1985) Women … a world survey, Washington, D.C.: World Priorities. J. Seager and A. Olson, (1986) Women in the World, London: Pan Books

On a continental scale Latin America is distinguished by high levels of female literacy but low levels of participation by women in the formal workforce, especially in agriculture. This is almost a mirror image of the situation in Africa, south of the Sahara, where women play a major role in agricultural production but suffer from low levels of literacy and life expectancy. The interrelationships between these indicators will be examined in the following chapters.

Key ideas

1 All social groups have developed a division of labour by sex but this varies cross-culturally.

2 Economic development has tended to make the lives of the majority of women in the Third World more difficult.

3 The universal validity of both gender-neutral development theory and of feminist concepts derived from white, Western middle-class women’s experience is being questioned.

4 Indicators of quality of life show great variation between countries and between women and men.

5 Measures describing the role and status of women display distinct regional patterns.

2

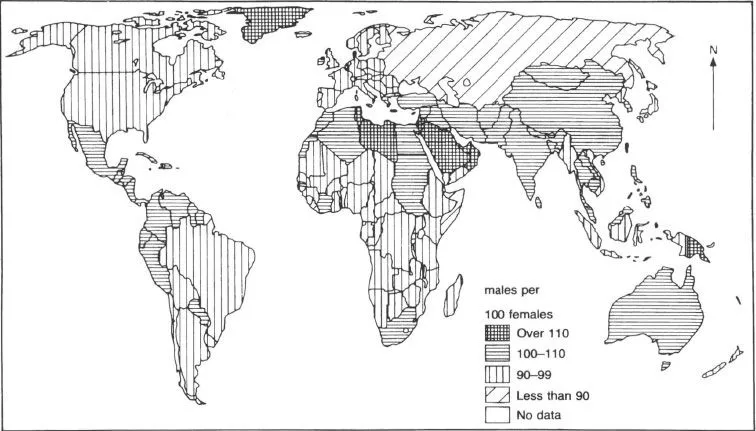

The sex ratio

It might be expected that the sex ratio, or the proportion of women and men in the population, would be roughly equal everywhere. Figure 2.1 shows that this is not so and there is quite marked variation between countries. Explanations of these spatial patterns reveal differences both in the relative status accorded to women and men and in the quality of life they enjoy in the Third World.

More males than females are conceived but women tend to live longer than men for hormonal reasons. Boys are more vulnerable than girls both before and after birth. The better the conditions during gestation, the more boys are likely to survive and the sex ratio at birth is usually masculine. However, if basic nutrition and health care is available to the whole population, age-specific death rates favour women. In the industrial market economies these factors have resulted in ratios of about 95 to 97 males per 100 females in the general population. Sex-specific migration or warfare may distort the normal demographic pattern. Typically, however, in the absence of such factors, a male-female ratio significantly above 100 reflects the effects of discrimination against women.

In the world as a whole there are some 20 million more men than women because of masculine sex ratios in the Middle East and North Africa, and the very marked imbalance in the huge populations of China and India, where there are 21 million more Chinese men and 27 million more Indian men than women. Between 1965 and 1987 the sex ratio in some countries such as Canada, Australia, the United States, Kuwait, Somalia and Sri Lanka became more feminine but in the world as a whole it became more masculine. In this chapter we examine the reasons for these differences.

Figure 2.1 Sex ratios

Survival

Life expectancy at birth is the most useful single indicator of female general well-being in the Third World. In the developed world average female life expectancy at birth varies only between 81 years in Japan and 73 in Romania, but in the developing world the range extends from 79 years for the women of Hong Kong to 37 in Afghanistan. Women have the shortest lives in the countries of tropical Africa and South Asia. Countries such as China, Haiti and Somalia, with similar per capita Gross National Products to that of Afghanistan of approximately US $300 per year, have female life expectancies of 71, 56 and 49 years respectively. These figures demonstrate that even poor countries can improve the general well-being of their women citizens by adopting a basic needs approach and ensuring that food, health care and education are accessible to all. Within countries marked regional differences may exist: female life expectancy in Malaysia was 59 years in 1965 rising to 72 in 1987 while male life expectancy increased from only 56 to 68 years, but in the east-Malaysian state of Sabah female life expectancy in 1970 at a mere 45 years was three years less than that of men.

Male and female survival chances vary at different points in their life cycle. In the first year of life boys are more vulnerable than girls to diseases of infancy and in old age wom...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The sex ratio

- 3 Reproduction

- 4 Women and work in rural areas

- 5 Women and work in urban areas

- 6 Spatial patterns of women’s economic activity

- 7 Women and development planning

- Further reading and review questions

- Index