Chapter 1

New Horizons

You know that the more magnificent the prospect, the lesser the certainty, and also the greater the passion.

Freud

Chapters 1 and 2 are twinned. This chapter concerns scale, scope and intellectual depth. Chapter 2 adds moral substance. The synergy of intellectual and moral forces would be unbeatable except we are far from establishing the conditions for this to happen. But we are making progress and gaining a clearer understanding of what remains to be done.

I start with the case of educational reform in England. A word of explanation: The United Kingdom consists of four separate educational departments — England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. I focus here only on the recent reforms in England.

To illustrate what I mean by “new horizons” I will identify a first level of accomplishment, only to be followed by the realization that there are richer horizons that lay beyond. At the time of writing, late 2002, we are in the final year of a four-year evaluation of the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategy in England (Earl et al., 2003). NLNS is the most ambitious large-scale reform initiative anywhere in the world. Baseline measures were established in England in 1996 using the performance of 11-year-olds in literacy and numeracy as the initial markers. A comprehensive top-down strategy was then orchestrated which invested in accountability mechanisms and capacity-building (professional development, quality instructional materials, new leadership roles) (see Barber, 2001). A team of us at the University of Toronto was contracted to monitor these efforts and to feed back our assessment on an ongoing basis of how well the process was doing and how it could be improved.

Government leaders announced four-year targets and committed to their achievement. In particular, the baseline measures indicated that in 1996, 57 percent of 11-year-olds were achieving acceptable proficiency in literacy, and 54 percent were so doing in numeracy. The targets for 2002 announced in 1997 were 80 percent for literacy and 75 percent in numeracy. The Secretary of State for Education and Employment, David Blunkett, said that he would resign his post as minister if the targets were not attained (he is, of course, no longer minister, being promoted largely because of his success in education).

This is large-scale reform. There are 19,000 primary schools involved. In effect, the government set out to improve the vast majority of schools in the system, at least as far as literacy and numeracy are concerned, within a four-year period. The results at the end of the initial reform period, 2002, are displayed in Figure 1.1 While the targets were not met the results are impressive. Literacy achievement has improved from 57 percent to 75 percent, having leveled off the last two years. The main reasons for the shortfall are that writing lagged behind reading and girls outperformed boys. Greater attention is being paid to both these components in current strategies. Mathematics scores increased from 54 percent to 73 percent just short of the 75 percent target. These are remarkable achievements across a large, complex system. (I raise a more fundamental question shortly as to whether centrally-driven strategies eventually run out of steam.)

This is not the place to discuss all the ins and outs of the strategy. There are debates about possible side effects such as burnout, loss of creativity, and some questions about the validity of some of the measures in literacy. As evaluators, we have no doubt, however, that literacy and numeracy have improved substantially in England over the four-year period. In Chapter 2 I will add some impressive data on the moral question of closing the gap between high and low performers.

Literacy: Percentage at level 4 or above

Numeracy: Percentage at Level 4 or above

Figure 1.1 Results of school reform in England (DfEE, 2002)

New Horizons 3 In any case, I am going to call the large-scale improvement of literacy and numeracy “new horizon #1.” We will see the same improvement in school districts in the United States (see Chapter 5). In other words, over the last five or so years we have learned how to improve literacy and numeracy in large systems (school districts, and in the case of England, a country). More work needs to be done, but these are, indeed, impressive improvements.

Despite these accomplishments, which most of us would have said could not be done within a five-year period, I will now argue that these changes are not deep, only first steps in terms of the deeper reforms that are required for the twenty-first century. Here we turn to “new horizon #2” to talk about the substance of what lies ahead. I will use four examples: the England case, a study of the implementation of new mathematics in California, some hard questions posed by Richard Elmore about the limitations of current practice in schools, and improvement of the teaching profession in Connecticut.

A curious thing happened in England during what I will call Phase I reform (1997–2002). As literacy and numeracy scores rose, the morale of teachers and principals, if anything, declined. I believe that the reason for this is (a) the basic working conditions of teachers did not change to enable them to become fully engaged, and (b) the literacy and numeracy strategies, per se, were not actually aimed at altering this more fundamental situation.

Put another way, literacy and numeracy improvements are real, but only a first step. Engaged students, energetic and committed teachers, improvements in problem-solving and thinking skills, greater emotional intelligence, and, generally, teaching and learning for deeper understanding cannot be orchestrated from the center (although as we shall see, the center has a crucial but different role). High-powered learning environments which are intensively learner-centered, knowledge-centered and assessment-centered require great capacities and commitment from the entire teaching force and its leadership, and thus will require different strategies from the ones currently employed to address literacy and numeracy (see Bransford, Brown and Cocking, 1999).

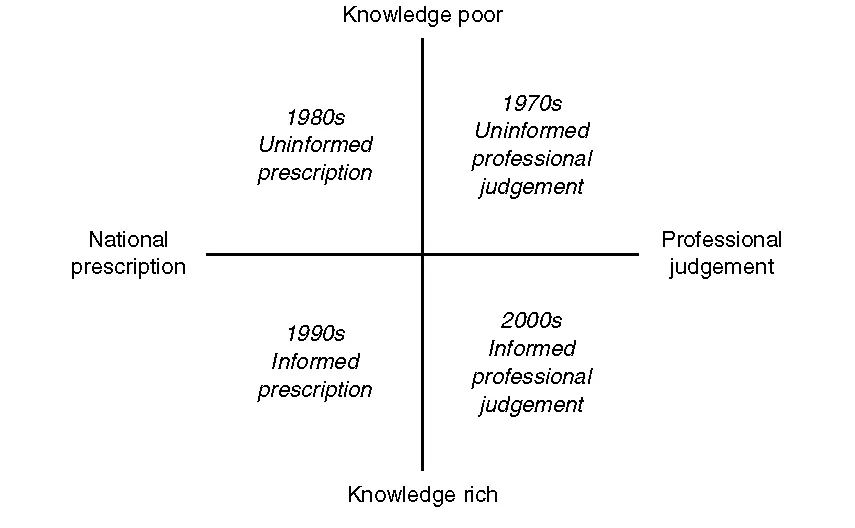

Based partly on our criticism that Phase I strategies had almost reached their limit and partly on the government's own concern that more fundamental transformation was required if teachers were to be fully engaged, English policymakers are now grappling with the question of what should be the policy set for Phase II reform. One of their initial formulations is extremely helpful in viewing new horizon questions in historical perspective (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Knowledge poor–rich, prescription–judgment matrix (Barber, 2002)

Crossing knowledge poor–rich with prescription–judgment, the evolution of reform strategies over the past four decades is neatly and generally accurately portrayed. Prior to accountability and in the days of loosely coupled professional individualism, the 1970s is seen as “uninformed professional judgment.” External ideas did not easily find their way into schools, and even if they existed or got there they did not flow across classrooms. There was little quality control of innovations that were attempted although there were pockets of productive collaboration through teacher centers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Growing concerns with the performance and accountability of school systems, marked in the United States in 1986 by A Nation at Risk, resulted in a set of state driven prescriptions for reform which can be accurately described as the “uninformed prescription” of the 1980s and beyond. There may have been standards and goals (even these in many cases were ill-conceived), but there was virtually the complete absence of any capacity-building strategies and resources for how to get there.

Concerned with national or state-driven reforms, some entities like England moved into a more carefully considered era of “informed prescription” in the 1990s. Mind you, the label is debatable in two respects. There remained the majority of states and nations that were not exercising informed prescription. And for those that claimed they were, again England, who says they were informed? Nonetheless, there was a deliberate process to base policies and practices on the New Horizons 5 best of research and knowledge, and further, to continually refine prescriptions through further research and inquiry.

Informed prescription, the argument goes, can take us to the first horizon, but not much further. For deeper developments we need the creative energies and ownership of the teaching force and its leaders. Hence, the current emphasis on “informed professional judgment.”

These formulations are exceedingly helpful as an overview but there are several key questions. First, does a decade of informed prescription create the preconditions for moving to informed professional judgment, or does it actually inhibit it by fostering external dependency? Second, is there the danger in moving to informed professional judgment that the gains of valuable prescription will slip away? Put another way, did informed prescription actually hamper the creativities of teachers, or did it rein in a range of permissive but highly questionable practice that went under the name of creativity and autonomy? Third, how do you move, anyway, from prescription to autonomy? We might be able to portray what informed professional judgment might look like but the pathways for getting there will be enormously complex and different depending on the starting point. For example, if trust, morally purposeful policy, coherence, capacity, knowledge management and continuous innovation are conditions for collectively informed professional judgment, how do you establish these “facilitative system conditions”?

The point is not to answer these questions right now, but rather to say that we are finally getting somewhere. Part of this development is to begin to focus more on the system and policy levers in order to alter the working and learning conditions in schools (see Chapter 6). For example, the British government commissioned PriceWaterhouse Coopers (2001) to study the working conditions of teachers and head teachers (in their own right and in comparison to business and industry). PWC concluded that if the goals of the educational system are to be realized:

An essential strand will be to reduce teacher workload, foster increased teacher ownership, and create the capacity to manage change in a sustainable way that can lay the foundation for improved school and pupil performance in the future. (p. 2)

The horizon question, of course, is how do you foster widespread teacher ownership? But it is still the right question and establishes the agenda as it should be. In Chapter 6 we will return to the role of policy with the point that the policies and strategies which were successful in Phase I (i.e., improving literacy and numeracy) will not be the ones required to go beyond Phase I. David Hargreaves (2002: 2–3) makes this very case in talking about “tests for creative policymakers” such as a new levers test:

Many initiatives have taken the form of a new lever that has worked well. But all levers have their limits. Educational processes are very complex, affected by many variables, so the amount of improvement any single lever can effect is smaller than reformers might wish. Moreover, when a new lever has demonstrable positive impact, policymakers have a tendency to push the lever beyond its limits. For example, in England, “targets” — for students teachers, schools, local education authorities — have had a real effect on raising standards, but because targets have worked, policymakers demand yet more of them. The danger, of course, is that this can induce resistance to the very notion of a target and thus ruin what was originally a very effective lever. Rather than pushing an old lever beyond its natural limits, policymakers would be wise to search for new levers. So the new levers test asks: Has this reform reached its natural limits and should a new lever be sought to complement or replace it? (emphasis in original)

Developing new levers is a challenge of the highest order because it must result in unleashing energy, commitment, resources and learning on a very large scale to accomplish thing never done before.

Three additional cases in point illustrate the scope of this challenge. First is Cohen and Hill's (2001) study of California's decade-long effort to change and improve mathematics teaching. Their conclusion is stated up front:

The policy was a success for some California teachers and students. It led to the creation of new opportunities for teachers to learn, rooted either in improved student curriculum or in examples of students’ work or the state assessment or both. Teachers were able to work together on serious problems of curriculum teaching and learning in short-term professional communities. The policy also helped to create coherence among elements of the curriculum, assessment, and learning opportunities for certain teachers. Such coherence is quite rare in the blizzard of often divergent guidance for instruction that typically blows over U.S. public schools. Only a modest fraction of California elementary teachers — roughly 10 percent — had the experiences just summarized. (p. 9, emphasis added)

Cohen and Hill argue that three “policy instruments,” in combination, resulted in improvements: curriculum, assessment, and teacher learning:

The things that make a difference to changes in their practice were integral to instruction: curricular materials for teachers and students to use in classes; assessments that enabled students to demonstrate their mathematical performance — and teachers to consider it — and instruction for teachers that was grounded in these curriculum materials and assessment. (p. 6)

Cohen and Hill also found that norms of collaboration among teachers were generally weak, and that collaboration per se does not mean that new ideas would necessarily flourish. This requires explanations and leads to a more useful merging of our prescription/ judgment combination. Cohen and Hill again:

Stronger and more broadly supported professional norms of collaboration were associated with conventional ideas [in mathematics], an outcome that shows that professional communities can be conservative as well as progressive … Professional contexts are likely to bear on teachers’ ideas and practices only when they create or actively support teachers’ learning of matters closely related to instruction, and most professional collegiality and community in American schools is at present disconnected from such learning … The key point is that the content of teacher learning matters. (pp. 11–12, emphasis in original)

Now we are getting somewhere. While Cohen and Hill may rely too heavily on “the informed prescription” of (in this case) mathematics reformers, the conclusion is the same. Let us focus on what we mean by “informed” and not make the error of relying solely on professional communities, or for that matter on external expertise. Both are required, i.e., reforms need to be pursued under conditions which maximize intensive teacher learning, involving external ideas as well as internal ideas, interaction and judgment.

In building professional learning communities, Andy Hargreaves (2003) reminds us that this is not a straightforward matter. He makes the point that many versions of apparent professional lea...